Ep. 190: Germane Barnes Practices Architecture with the Prowess of a Winning Point Guard

Germane Barnes knew he’d be an architect at age 6, before he even knew what that meant. Growing up playing basketball, he honed skills he now deftly deploys in his creative practice. After a tumultuous period spurred by devastating loss, he has taken the architecture world by storm. He’s swept the most prestigious prizes and is poised to become one of the most notable architects of our lifetime.

-

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to the wildly successful young Architect Germane Barnes. His award-winning practice, Studio Barnes, examines, through historical research and design speculation, the connection between architecture and identity, architecture’s social and political agency, and the built environment’s influence on black domesticity. He is also an Associate Professor and the Director of The Community Housing & Identity Lab at the University of Miami School of Architecture. He received his Bachelor’s in Architecture from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and his Master’s from Woodbury University where he was awarded the Thesis Prize for his project Symbiotic Territories: Architectural Investigations of Race, Identity, and Community…And he’s pretty much been on a well-deserved winning streak ever since…He was awarded a Graham Foundation grant for his project: Sacred Stoops: Typological Studies of Black Congregational Spaces, which is an investigation of the porch and its role in the African-American community, he was included in a major exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, that same year he won the very prestigious Rome Prize, the Harvard GSD Wheelwright Prize, and a United States Artists fellowship. This month - his work is in the Venice Architecture biennale. It was fascinating to learn just how much his architecture practice is informed by the skills he honed on the basketball court - and the whole story plays out like one of the most exciting games you’ll ever witness… Here’s Germane.

Germane: My name is Germane David Barnes. I live in Miami, Florida where I have a practice named Studio Barnes which is design and architecture focused. And the reason I do what I do is because one, I'm not a fan of reading so most jobs that involve reading and writing were not on my radar. And second because I would like to leave a lasting impact on the built environment.

Amy: You grew up in Chicago on the west side?

Germane: Yes, yes. In the city of Chicago. A lot of people like to say they're from Chicago. When they're from a suburb. But no, I'm from the actual city.

Amy: Talk to me about your childhood. What kinds of things made an impression on your young brain? What was your family dynamic like?

Germane: It's interesting because I've only ever wanted to be an architect but I had never met any architects.So I don't know where it sort of came from. One of my earliest memories that my mom loves to regurgitate any time she meets new people is, “When he was six he was with his cousins and they were doing a 'what I'm going to be when I grow up' type exercise at his aunt's house and Germane said that he's going to be in the NBA and be an architect at the same time.” So I always say obviously the basketball thing never came to fruition but the architect thing did. But it's interested. This is over, this is 31 years later six to 37 and architecture is still there. So it's very, very peculiar that I've never met an architect, didn't really know what architects did, I don't even know where I heard the word before. But by six I was able to say, “I'm going to be an architect.”

Amy: That is wild.

Germane: Yeah, it's rare.

Amy: That is wild. I don't want to leave the basketball piece alone because I'm assuming you did play growing up.

Germane: Yeah. Yeah, I played all the way through varsity, four-year letterman, and then got to time for college and my coach was like, 'hey do you want to play in school?' And I was like, 'hey man, you and I both know I'm not going to the NBA or anything.' So I am smart enough to have a scholarship for this design stuff so I'm just going to go ahead and focus on that and I'll still play basketball. You'll catch me at the wellness center at the University of Miami where I teach, playing basketball two or three days a week with a bunch of students and stuff because I'm still in pretty good shape.

Amy: I love it.

Germane: But it stops there.

Amy: I love it and I'm interested. If you can draw any parallels to basketball and architecture because...

Germane: Oh, absolutely.

Amy: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So, spell that out for me. I'm super interested in how sports and design overlap and I think it's something that people don't think about enough but it's really, really related.

Germane: I tell people all the time I wouldn't be this successful in architecture if I didn't have so many years of basketball experience. I would not have it.

Amy: I believe you. Unpack that a little bit. Why do you think basketball supported you in architecture?

Germane: Sports in general if you play at a very competitive level is forces you to learn discipline. You don't have a choice. If you care about this and you love this and you want playing time and you want success then you have to sacrifice a lot and it builds up a competitiveness that sort of becomes and defines you. So for me from playing organized basketball from fifth grade until my senior year of high school, what's that, 11…12 years, sometimes playing on two or three teams at one time, like having to travel to Wisconsin for a game and then coming back, you learn very quickly time management. You learn very quickly priorities; you learn very quickly 'oh I have to outwork that other person' because while I'm here goofing around they're probably in the gym putting up 500 shots and I'm not. So when it came time for studio culture, oh you think you're going to make 10 models? I'll make 15. Or you're going to make eight drawings. I'll make 12. It's never running from the competitiveness of it. I remember when I was in graduate school there was a young man named Wallace Fang and Wallace is like the greatest hand model maker I've ever seen in my life and at the time I wasn't very good at making models by hand.

So I was like, you know what? I'm going to sit next to Wallace because he's going to push me. Sitting next to him and watching all the stuff, 'I need to be in here working more.' These were things I developed playing sports and I think the biggest way that it helped me was when it came to critiques and reviews which we know can be crippling to a person's confidence because a lot of times you have a series of your peers or people you admire that are essentially telling you how either this is the greatest project of all time or the worst project of all time. There's rarely anything in the middle and most of the time they're telling you it's the worst thing (laughter) that they've ever seen before and I've seen a lot of students crumble under that pressure. Meanwhile I'm thinking this is nothing compared to a basketball game I've had. All you can do is tell me this project isn't good. If I go and miss that defensive assignment, we might lose the game (laughs). Or if I turn the ball over, I might not get back in for the next two quarters.

So, I was always able to put things in perspective that way because of sports. Then I think the other thing is affords me is the ability to communicate with people because so the position I played in basketball was point guard which is essentially the leader on the court. Think of it as the coach makes the plays and then the point guard makes sure that everybody knows their roles and where they're supposed to be. That sounds like an architect to me that is leading a bunch of consultants. Of saying, “You do this, you do this, you do that,” and understanding how to communicate with those people because with some players I knew I can yell and they would play better. Others I knew I had to give them a pat on the back or be very encouraging and they will play better. So all these things have helped me as an educator and as a professional.

Amy: I see it. I believe it. And I also want to ask you about just while we're on this topic, it would seem to me that you would have to learn a lot of fast decision making, a lot of very 'feel your way,' 'understand the flow' kind of… You know the game so well you can see three steps ahead and how things are going to go so you make these sorts of on-the-fly decisions. Has that helped you in terms of being flexible and adaptable in your work?

Germane: Absolutely. I think one of the best compliments I typically get from colleagues or fabricators that I work with even if it's the first time, it's you’re very easy to work with. And that goes back to me knowing I can't be stiff. I have to be able to change because if I'm playing a game and this person starts making every single shot we've got to be willing to change. If we don't change up the scheme we'll lose this game. So, when I'm doing real work if somebody says, “Well Germane, this wall doesn't do or the drawing we originally sent you is not representative of what's here in the space, is that okay,” I can't be like, “No, I was planning for this one thing you sent me and now it's this other thing so how can I, it's too late to change.” My thought is okay, let's shift. Here's how we do this thing, let's keep going, and then we move on from there.

Amy: And that also demonstrates a kind of respect and understanding for the rest of the team. Like in this case the trade laborers. And the people who are on site. And when you respect what they have to do and what their role is in the whole game and you're playing to support them in terms of their strengths and your strengths, that seems like a much more fluid and collaborative kind of arrangement. A lot of times we hear of so much contentiousness between let's say the creative class and the trade, and that really frustrates me. But it sounds like you've got a nice dynamic going.

Germane: Absolutely. Everything that we do we put everybody's name on it. Any time I win an award or a project gets a lot of notoriety I'm always sure to say 'this is who built it, don't think I did it, we just designed it.' Or 'here's the teammates that did it,' because again it goes back to my theory in sports where if I'm playing with four other people and we go eight possessions and one guy never gets the ball. He's doing all this hard work that is going unseen. He's just looking at us like, 'why aren't you guys passing it to me?' He's going to stop working hard. He's going to stop caring and the next thing you know you lose the game because he's like, 'well you didn't care about me so why should I care about the team?' I keep these same ideals and the funny thing is when I'm playing basketball sometimes my teammates are like, 'why are you passing him the ball, he's terrible.' I'm like, 'because he's doing all the stuff you don't want to do.' If I don't give him the ball a few times he's going to stop doing those things and then we're going to lose. So when it comes to the real business it's like, 'why are you putting their names on it, they didn't have anything to do with the concept, etc.' And I'm like, 'because they built it.' If they didn't build it we would have to do it and if we had to do it it would not have been this clean.

Amy: (Laughs) Yeah.

Germane: So, then what's the problem? I mean these are definitely things that have definitely paired together.

Amy: That's keeping the big picture in mind and that's also understanding not only the team dynamic, but that creative ownership. Pride in someone's work is actually, you know, a key piece of the intention of the built work and if you put love into designing the concept and the intention behind it, then you want it to be built with love, too. That means everybody has got to be respecting each other.

Germane: Absolutely.

Amy: So, you knew you wanted to be an architect from six years old.

Germane: Yeah.

Amy: Without any role model for that. How did that grow and foster in your brain? Did you start seeking out examples of architecture?

Germane: No.

Amy: No? (Laughter)

Germane: No.

Amy: It was just this abstract concept?

Germane: Yeah, sometimes I say stories like these are ones that make you believe in serendipity and destiny.

Amy: Yeah. (Laughs)

Germane: Right? Because it's just so bizarre. In that regard...

Amy: It's like assigned to you before you were born and you were like 'okay.'

Germane: No, look. I'm going to tell you something. It's going to be even more crazy when I say a couple more things that actually work together, Amy. That’s that I know I’m going to be an architect at six, right. I have an older cousin. My older cousin is really good at sketching, really good at drawing cartoon characters and things and there was a Manga called Dragon Ball Z that used to come out when we were younger. It’s still out today but when it originally came out we were much younger. He would draw the characters all the time and in my affinity for wanting to be like my older cousin I would just start drawing them, too. So I’m drawing all these things but again never a building, I don’t think I ever drew a building until the seventh grade. And the reason why I said till the seventh grade is because the elementary school I went to, seventh grade year you do a glass diorama or project, seventh and eighth graders.

That year the eighth graders had the Amazon rain forest and they did this whole installation in our hallway on the third floor. The seventh graders were on the second floor and so we did Frank Lloyd Wright as ours. Every single student got put into pairs and you had to build a small model of a Frank Lloyd Wright home that was given from the list. I picked the Guggenheim Museum. Me and my friend, Pedro, we built a model of the Guggenheim. That was in the seventh grade but what really gets trippy is we did a field trip to Frank Lloyd Wright’s home in Oak Park because you know here in Chicago you have very good access to it. So as we were driving down the street on the yellow school bus I see my house and I’m like, ‘why are we by my home?’ Then we go a little bit further and I’m like, ‘I play in that park, where are we?’ Come to find out the park I played in as a kid is directly across the street from Frank Lloyd Wright’s home.

Amy: No way!

Germane: Literally across the street. So this entire time I’m literally just being a kid, running around playing and stuff, not knowing I’m literally across the street from Frank Lloyd Wright’s house. So I go inside. I come home to mom like, “Ma, you know the park we play in all the time? You know it’s across the street from Frank Lloyd Wright’s home?” And she’s like, ‘never knew that.’ And then we realized there’s plaques all over the place, there’s street signs and things, and it just all melds together. It’s a sort of insane thing that again, I don’t know how all this stuff happens.

Amy: Wow! Well, I mean just to get even more meta that’s an example of how the built environment seeps into your subconscious and has an impact on the world around you and if we design the built environment for the world we want to see, then we can make it a reality.

Germane: It was just so insane. There was a restaurant down the street from there called Giordano's, it’s a famous Chicago pizza place. We would go there a lot and then when I was in from three to five, I had one of those parents that just put you in everything. I’m going to find ways to keep your busy so you never get a chance to just sit down and do nothing. So I never had any free time and from three to five I did tap dance and ballet and all that kind of stuff as a kid and that was on the exact same street as the park, as Frank Lloyd Wright’s house, etc. You just take that one street all the way down so I don’t know how many times I probably made that drive not realizing what I was seeing but me and my older siblings would play this game of ‘that’s my house.’ You would see a very nice house through the window, ‘that’s my house.’ The first one, the quickest one to see the biggest, most glamorous, beautiful object, you get to claim it. And if you say it before somebody else then it’s yours. There are a lot of very beautiful old homes at Oak Park that you see that make you really want to say ‘I wish that was my house’ that you’re driving past.

Amy: Wow. That is serendipity. Seventh grade, you’re realizing you played across the street from a Frank Lloyd Wright house and when you were doing this project and going on this field trip, was it clicking for you? Were you also getting more inspired by architecture and thinking ‘oh yeah, this is why I want to do it?’ Or was it like, ‘this is not what I thought it was going to be.’

Germane: It was probably more reinforcement. It’s funny, this was maybe five or six years ago because I’m still in touch with Pedro, the guy from kindergarten, because we went to kindergarten through eighth grade together and then we went to high school together. So still, still inextricably linked (laughter) all these years later. I think I posted something on my Instagram page and he sent me a DM and he said, “Dude, you’ve been talking about this since we were six.” (Laughter) And I was like, ‘it’s crazy that you still remember that.’ That literally this is the only thing I’ve ever wanted to do. Sometimes people doubt the voracity of my story and I’m like, ‘nah man, this is the honest truth.’ There has never been anything else. Obviously there was the basketball aspect, but aside from that there was never anything else I wanted to do.

Amy: Man, that was not me. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I had to go the circuitous route. But talk to me about your teenage years. If you’re already on the path to architecture, you’re playing basketball and that’s still a big piece of your life. Where did your teenage angst and growing pains fit in and what did they look like for you specifically in terms of you finding your adult identity?

Germane: I can honestly say I’m lucky and my sisters will tell you they hate this about me, that I’ve never had the awkward phase.

Amy: You never! (Laughs)

Germane: I never had the awkward phase.

Amy: That is not fair.

Germane: Yeah, they will tell you they hate it. Physically I never went through it. I’ve had the exact same face I’ve had since I was a kid just minus the mustache and a beard. So I never actually went through the awkward phase and they used to hate that about me. It’s like, ‘you’re good at everything, the moment you grab something you just catch on.’ I think it’s just a dexterity but I tell them all the time that it’s because I’m the youngest that I was able to learn from them. I have an uncle that would always tell me there’s two types of people, the people who need to touch the stove to find out it’s hot, or those that believe you when you tell them that the stove is hot. I’ve always been the latter in that, okay clearly I think you care about me so why would I think you’re going to give me bad advice. You tell me not to do these things, I’m just not going to do them. You tell me to do those things, I’ll just do them. If you tell me ‘Work hard,’ okay cool I’ll work hard. If you tell me ‘Don’t go to that neighborhood,’ okay I won’t go to that neighborhood.

I don’t need to be like Simba and go run and see if what dad tells me is true or not. Some people tell you that is a difficult way to live because you might miss out on amazing opportunities because somebody else might have fear and they put that fear on you and that may be true. But I think more times than not it’s somebody that cares about my well-being and they want that for me. So my high school years were super, super easy. I went to one of those high schools that it seems like you’re in movies, like you see it in TV and you’re like, ‘high school is really not like that.’ My high school was really like that. It was Walter Payton College Prep. We were the first class admitted so it was only us as freshman so I don’t know what it was like to have upper class-men. Again, no awkward phase because there was nobody older than us, it was just us. Then my sophomore year it was us and new freshman, junior year, us, the sophomores and the new freshman.

Amy: Right, so you were always on top of the stack. (Laughs).

Germane: Yeah, I never knew what it was like. And the high school I went to was extremely well resourced which goes through a lot of bad issues about Chicago public schools and that it’s public, but it’s selective enrollment. So we had a planetarium in our building. Everybody got their own laptop. We had off campus lunch. We had Thursdays where you can play ping pong instead of going to class. That was the kind of school that I went to so I am getting this amazing education which is all reinforcing my desire to go into artistic fields. We have tons of art classes and I’m taking all of them. Because we had access to them. Like I take photography at the Art Institute of Chicago as an elective course. I’m taking drawing and painting. I’m doing all of these things. That’s because at that point I knew that some of the best architects in history been painters and artists before they became architects. If that’s what they did then that’s what I’ll do. Similar to basketball. All right, if this person trained and watched this tape, I’m going to do the same thing as that person. So I mimicked a lot of the things I saw from the ‘greats’ as the way they got there and so I did the same thing. The first job I ever had was actually as a painter painting murals for the library in my neighborhood.

Amy: Oh really?

Germane: Yeah, it was for the Mayor Daley’s Kid Star Program. It was this way to get 14 and 15 year olds work permits where you’re getting paid but you’re not really having a real job and mine was doing painting. So I spent the entire summer at Austin High School just learning to paint and then painting and doing the mural at the end for the local library and I got paid for it. That was my first ever job.

Amy: And were you doing it with a team of people so it was collaborative as well?

Germane: Yeah. It was eight or nine of us high school kids. Some of them went to that high school, Austin High School, some of them were from the neighborhood. I was from the neighborhood but I didn’t go to that high school. My high school was 45 minutes away. We all were learning together and everybody could draw but a lot of people didn’t know technical skills. You’ve got to remember I’m just copying my older cousin. I’m not getting formal training. Then I don’t know if you remember these things but the scholastic book club things they used… right. You used to have the pamphlets like ‘how to draw a superhero,’ or ‘how to do this.’ So I used to get all those books. I was very fortunate to have parents who have money and were able to buy these things for me. As a kid any ‘how to draw thing’ I had them all but it was self-taught as opposed to me having an instructor show me how to do the things.

Amy: I think this is interesting because you’re in a profession that requires a lot of critical thinking and yet you’re describing a childhood where you at least had a lot of trustworthy role models in your life. Where you didn’t have to question the kind of information that was coming your way. You could just absorb it and move forward because you didn’t have to learn the hard way on a lot of things.

Germane: Mhm.

Amy: Well I learned my artistic skills, while you were painting murals I was perfecting the curlicue on the top of my Dairy Queen ice cream cup thing.

Germane: Gotcha. (Laughter)

Amy: And getting the banana splits just perfectly symmetrical.

Germane: Gotcha. I did have those types of jobs, too. But it definitely started with painting and then became other stuff.

Amy: So architecture was never in question. How did you decide on your college trajectory? Like where you wanted to go to school and where you wanted to study.

Germane: That was a series of unfortunate events. This is where we start to hit a bit of a few roadblocks because everything is super easy at this point just to be totally honest. Everything is super easy. Now I’m in my junior year of high school, we’re taking the PSATs which everybody takes in the US, and I’m getting top five percentile in everything so every single school is writing and saying, “Hey you should come here.” I’m getting letters from Princeton, I’m getting letters from Yale, I got accepted to some Stanford program during the summertime which if you accepted this offer you automatically get into Stanford as a freshman when you come. My mom always taught me, my mom and dad, that the summers were mine, I didn’t have to do work during the summers so long as I performed during the school year. So when I saw the letter from Stanford I was like, ‘you think I’m giving up my summer to go and be a student?’ You’re insane. That’s not happening. So I keep on going but then one day I come home and one of my older sisters was there and she was attending Howard University in DC, a historically black college, and that’s when we found out she had cancer. She had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She told me about it. I was distraught and I’m taking AP courses at my high school and the AP courses are first thing in the morning from 07:00 to 8:00 and then 8:00 until 9:00 am. When she was there I would go to the hospital every single night to sit and hang with her because she just hated being there. So she’s not enjoying it at all but I’m trying to be there for her and be supportive. The nurses knew me on a first name basis because you’re not supposed to be there if you’re not the parent but I’d be there so late in the day that it would make me sleepy before class in the morning so my grades started to go down a little bit but not to a point where it affected where I would get into school. At this point she’s not getting better so the chemo is just sustaining, it’s not removing the cancer so I would make the decision I’m not going to apply to the schools I actually want to go to. I’m just going to go to Howard University or I’m going to go to University of Illinois so I can be there with her in either scenario. I end up going to the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign.

Amy: It’s a great school.

Germane: Yeah, for architecture. Absolutely. So it wasn’t like they were bad choices, but I had dreams of going to Syracuse for some reason because again I loved basketball. The Orange Men was a great team and they had a great architecture program. I was like, ‘look I can pair these two things together.’ My mom wanted me to go to Princeton because they took her out to dinner, literally recruited my parents. ‘We’ll take you out to dinner, we have basketball here, your son can play basketball, and he can study architecture.’ I was like, ‘Ma, I don’t fit in at Princeton, I don’t think this will work.’ She’s like, ‘But it’s Princeton!’ And I’m like, “Yeah, but does it fit my personality?’

Amy: You’re so self-aware for a young man.

Germane: I just knew it wasn’t it. This is August. End of August we have what we call a trunk party. In our community, in the black community before you go off to college you have these sorts of parties that everybody comes and buys you things so that when you go to start your first day of college you have everything you need. I’m fortunate to have, again, financial privilege that my parents didn’t need to do this, but you have cousins and aunts that just want to contribute in some type of way so we had one anyway. That was the last time I saw my sister. We’re at the trunk party, this is maybe two weeks before I’m supposed to move in for school. I still have the picture on my phone, I will never delete it. Then school started no September 5th because it’s the day after Labor Day, University of Illinois, and then three days later I get a call from my dad on the 9th of September 2004 and he said, “Your sister didn’t make it.” Then all hell broke loose after that.

Amy: I didn’t know this about your life. I’m so sorry.

Germane: I can talk about it now, but at the time, not good. So everything was super easy until that point and then a year later one of my best friends who I’d known since I was in elementary school, he’s only two days younger than me, I’m November 16th and he’s November 18th, he was murdered. So all of the easy things I had experienced for myself began to sort of unravel for those around me and it really made me question a lot of things.

Amy: Thank you for sharing that. It makes me want to ask you what kind of questioning followed that and how did the grief play out in your life?

Germane: In the worst way possible. I got kicked out of school. So I went from one of the brightest kids you can imagine, smiling, happy, can hang with anyone, one of the jocks but also one of the nerds and that gets everything. It was never an issue to do anything and like I mentioned everything just came easy to me. I was like, ‘okay I’ve got it, I can figure that out, okay I’ve got it, I can figure that out.’ But then when it happened I was like, ‘I don’t know why this is happening.’ My sister is amazing, why was she taken from me? My friend, his brother was the problem. He was unfortunately killed because of his brother. So I’m like, ‘why do these things keep happening?’ At that point clearly none of this stuff matters because no matter how good you are everything can be taken immediately so I just stopped caring about school. You know what? I’ll just go, take my architecture studio courses because I’m going to be an architect, I saw enough times on TV that C’s get degrees. Clearly these grades don’t matter, I’m going to just do what I got to do. I’ll get this class, screw the rest of them. Nobody told me that if you have two consecutive semesters under a 2.25 in the School of Architecture you get kicked out of school. So if I were a gen ed major or some liberal arts major or kinesiology or something like that, 2.0s would have been fine. But in my college 2.25 was the minimum. No, nobody told me. So I had back-to-back semesters of a 2.0 and the next thing I know I get a letter in the mail that says, “Germane, you’ve been removed from the School of Architecture.” One of the weird things about the University of Illinois is at the time they used to do this special orientation for students of color. You were coming into a predominantly white institution, there would be 40,000 students, you need to know what resources you have so here are some of the cultural homes, the African American House, the Indigenous House. These are literal houses that we have that are led by these various ethnicities. So I was there for that and when you’re there you get paired with a mentor and you get paired with an advisor. The tough thing about design as you know, not a lot of people that look like me. So we had zero mentors that were in the School of Fine and Applied Arts, that is landscape, architecture, industrial design, urban planning, and architecture. Four different disciplines, not one black mentor. So when it came time to meet they were like, ‘sorry Germane, we cannot actually pair you with anybody because we don’t have anyone that represents those disciplines. I had the same advisor the entire School of Architecture had and that person didn’t really care. They didn’t have time. There was nobody else I could actually talk to and there was no black TAs, no black professors or anything so when all this stuff is happening, these tragic things are happening with my sister and my friend, I’m not talking to anybody. I’m just going to class every day and this is where the grief thing comes in. I’m just mad every single day. I’m mad at everybody. At my parents, they’re seeing it. I’m rude to my dad. I’m rude to my mom which are things I never do. And at one point my mom just snaps. She’s just like, “You have to go to therapy.” She sees the letter saying I’m kicked out of school. She sees I’m unhappy. She says, “I know you’re sad that he took your sister. I know you are. But God has a reason for why this happened.” Not to turn this into a religious thing, but she’s like, “You need to talk to someone.” So I go to my counselor and my counselor is like, “Why didn’t you tell us this was going on?” I’m like, “Who am I supposed to talk to?”

Amy: Right.

Germane: Like I don’t know who I must talk to. They were like, “Well, if you go to counseling and if you retake these classes over the summer, we will readmit you into the school in the fall,” so it actually didn’t interrupt my ability to finish in time but I had to go to counseling. I go to counseling, like one of the longest, biggest cries I ever had in my life were just like everything just came out and the therapist was just like, “How long have you been holding on to this?” I am like, “Probably way too long.” So, after that happened, go retake the courses, doing fine, back, I made it into the school. From that point forward, I’m dean’s list ever semester because now I don’t have this stuff on my shoulders any more, but those two semesters wrecked my GPA. So now, when it’s time for graduate school, who doesn’t look like a good candidate? Me, the kid who, amazing student his entire life except for this one year when all these crappy things happened and I wasn’t comfortable writing about it to graduate schools and telling people my personal business, so they are just looking at my GPA and thinking, this kid can’t hang, or he is not talented enough, not knowing the circumstances and I got rejected from all the graduate schools I applied to my first go round. It was tough.

Amy: I am happy to hear about that big, long cry. I am a fan of them. I do think they cleanse your system and it sounds like your faith was shaken, your faith in whatever you believe in.

Germane: Absolutely.

Amy: Having a catharsis is one piece of processing the grief but rebuilding your faith is another part of it and did that happen for you? Is it still happening for you? Is it an ongoing maintenance project or what?

Germane: It is definitely an ongoing maintenance project and I was definitely shaken quite a bit. I was questioning everything at that point. Things started to come back around and this is someone that is from a family that is like super, super religious and Southern Baptist because mom is from Arkansas, dad’s side is from Mississippi, so it’s super ingrained in the culture but I am questioning everything. I am like, why? This doesn’t make sense. Why? Go through the therapy portions and now at this point I am not getting into any grad schools and it’s 2008, which is the height of the recession. So now I am like, this is some sort of perverted twist that I pick the thing that I have only ever wanted to do and this is the worst time to graduate with a degree in architecture. This is when I ended up moving to Cape Town. So, I moved to Cape Town because I came across this internship opportunity through our career services department at the university of Illinois and when I go through there, I tell my parents. I am like, “Hey, I have an opportunity to go get a job in Cape Town but it’s unpaid, because again, architecture and stuff, most internships aren’t paid, unfortunately,” so I was like, “you guys have to pay for my rent. You have to give me money to spend and I will be there for like three or four months.” My parents were like, “Will this actually help you? Will this help you get a career?” I am like, “Absolutely.” They were like, “All right then, we’ll pay for it.” Again, thinking I am privileged, so definitely not lost on me. While this is happening, I am getting ready for this, I am actually taking a course at the local community college in Chicago and this is because, and again this goes back to the sports work ethic of, what are my deficiencies? What do I need to get better at? So I am like, they are looking at my portfolio, maybe the reason I didn’t get into grad school is because my models weren’t good or because my portfolio wasn’t as good. Not thinking it’s because of my GPA, I didn’t know at that point. So, I signed up for a one credit course at Trident Community College. I have my degree in hand already, I am with a bunch of high school kids and first year students who don’t know what they want to do, and they are all like, “Why are you here? You already have a degree.” But in my head, I am like, I see a deficiency, I need to get better at it. I don’t have a big enough ego to think I am above this. This is what I got to do; this is what I have to do. That is what I did. I literally spent that time there with a bunch of 17/18 year olds even though I’ve already graduated, to retake my freshman year of courses so that I can get better at them even though I didn’t need to.

Amy: Wait. I know you are there because you don’t have a big ego and you are polishing your game, but for those 17/18 year olds to see you being so dedicated, already with a degree, polishing your game, that’s a really strong vision to behold.

Germane: I have never thought of it that way but I see what you mean.

Amy: I just feel like you probably impacted a lot of those lives just by being there doing what you needed to do for yourself.

Germane: I thought of it just as I got to go do this. I got to get it done, and when I tell some of my students that, I am like, “Do you really care about? If you really care about it then you will sacrifice certain things.” They’re like, “What did you sacrifice?” I go, “There is a lot of stuff that you don’t know about me. You see a lot of the stuff today but it was not this easy to make it.” Then, when I came back from Cape Town, I applied for all of my grad schools again. I am like, alright, this reinvigorated me, I am super excited about this. This is amazing. I am going to go do this again, and now I can talk about what happened because I have gone through therapy, I know how to have conversations and things about it like it’s part of life. It’s happened, I continue to understand that these things happen to people.

Amy: Are we glossing over Cape Town?

Germane: I’m in Cape Town for three and a half, four months. I get there and in the first week I want to come back. I am like, “Ma, I want to come home.” Because I always tell my mom these things and my dad is like, “Dude, I just paid for this stuff. Your mom makes the decisions.” So I knew not to ask him, my dad would just say, ask your mom so I just said, “Ma, can I come home?” She is like, “How much longer do you have?” Like three and a half months. She is like, “Oh, then you will be there for three and a half months.” I am like, “Why?” She is like, “Well because I paid for it already and two, because it will get you out of your comfort zone. You need this.”

Amy: I like your mom.

Germane: She is intense. She is the sweetest thing ever but she is intense. She is like, no, you’ll be fine, and I told her the first day, I said, “Ma, I feel like I’m the only black person in South Africa.” She was like, “What are you talking about? There are black people there.” I am like, “Yeah, but I am American so it’s not the same. Everybody looks at me like I have a horn in the front of my head. Nobody treats me like I’m from the diaspora, everybody treats me like I’m an American so it’s weird. It’s extremely isolating because I don’t speak Xhosa. I don’t speak Afrikaans. I am just a regular old American here. That had its own rewards in that everybody rolled out the red carpet assuming I was going to be spending a lot of money because hey, this is a tourist, they clearly have some sort of financial capital. They will buy things. So, in that regard it was nice but otherwise I just felt alone for a very large amount of the time I was there, but then I started meeting other people in the internship program that were different disciplines but they were still there. That is where I began to build community, and through that it made things a lot better and after that I was like, “Ma, I never want to come back.” She was like, “Okay, well I’m paying for this so you have to come back.” I worked at this architecture office called Sean J Mackay Architects and it was in Rondebosch, which is a suburb of Cape Town. They do a lot of work in the townships of Khayelitsha and while we were out there doing that work, that is when I learned about community-oriented design because I never learned about it in undergrad, and so that is where literally my trajectory of work started. It was in 2009 when I was in Cape Town.

Amy: Well, I am glad we backed up and talked about Cape Town because that is a pivotal moment and it did get you out of your comfort zone. I mean, just to be in a place where you feel so othered and so isolated, I’m sure it perks up a different kind of survival skills.

Germane: Oh, absolutely.

Amy: Yeah. So, those four months sound like they were really formative in terms of shaping you and your, not just your career trajectory but your resilience. So then, you come back and now do we go to grad school?

Germane: Yeah. So, I come back 2009, I missed the first cycle so grad school starts 2010. I have to work for a year. So, I’ve always had a very strong work ethic, again I didn’t have to work, my parents would have been cool with me just being home and they just missed me. They were happy I was there. I was like, nah, I can’t just sit around doing nothing, I will get bored and Nike in Chicago had a job opening and the job opening was for a visual representative or something like that. Visuals are basically interior designers.

Amy: Oh, okay.

Germane: I was like, oh, architecture thing here.

Amy: Merchandising the retail outlets and stuff?

Germane: I was like, cool, this is basic interior design, it’s just architecture, I can get this job. So I applied for it. I get the job. I spend a year working at the Nike store downtown Chicago and then I am applying to grad schools again. I apply to six, I am talking about what happens. I’m like, “Hey, if you get me, you are getting an amazing student. I just got back from my first internship in Cape Town. Just take a chance on me. Trust me, everything is going to be good.” Four, no, three out of the six schools immediately rejected me. One of those schools was the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, I’m like how do you reject me? You knew what happened, they rejected me and then two other schools put me on wait lists. Then the third school was like, ‘hey, come for an interview.’ So, the third school was Woodbury University. They were like, “If you can come out for an interview, we can talk and this might help your candidacy.” Again, mom, dad, you need to put me on a plane to send me to California again. When I say these things out loud I recognize how hard it is for the average student to be able to just tell their parents to just do this kind of stuff, right.

Amy: I am hearing it too, yeah, and I also sense your gratitude.

Germane: Yeah, absolutely, and so they put me on a plane. I go there and I meet with Barbara Bester. So, I meet with Barbara Bester. Barbara is the director of the Grab program at the time, so Barbara is sitting there with Norman Millar, who unfortunately passed away to cancer a few years ago, and she says to me, “Hey, what happened in this little time period?” She is going through my transcripts. “Everything else seems really good, but something is not right about this little spell.” I am like, “Oh, you’re the first person to ask me this.” I was like, “That is when my sister died.” And she goes, “Wait. What?” I am like, “Yeah, my sister died from cancer and then one of my best friends was murdered and I didn’t know how to deal with it, so I didn’t care. My grades sucked.” And she goes, “Okay, this makes sense. You are in.” And I was like, “Wait, what?” She was like, “Yeah, you are in because clearly you are a really bright student, you just had some unfortunate circumstances so you’re in.” So, I was like, you will not regret this.

Amy: It’s amazing when a human just intervenes with the system.

Germane: Absolutely.

Amy: And leads with empathy. Jesus.

Germane: Absolutely. I told her, I said, “Look, you will not regret this. Trust me, you will get the best student you’ve ever had.” Then the other two schools, one of them was like, you didn’t make it off the wait list and then the other one was like, hey, if you come here for a talk, to talk with us, this might help your candidacy. So, I drive all the way there, it’s a five hour drive and I get there. There person who originally wrote me didn’t even meet with me. They put me off to somebody else. I was like, this was a colossal waste of my time and so it ended up being Woodbury and then when I got there, I won every single award that the school had. Thesis, highest GPA, everything. I was like, I told you you were getting a good student.

Amy: Okay, so you won every award. So, clearly they don’t regret letting you in but I want to make sure we talk about the thesis prize because, well, first of all, it sounds like an amazing project, so I would love to hear about that, but also I feel like so often, like the energy you put into your thesis work, is something that is the kernel of what will continue to grow and inform your trajectory and so it’s almost like going back to look at how the seed got germinated. So, tell me about the thesis work and winning the prize.

Germane: So, my thesis advisor is Jennifer Bonner of MALL. I had a bunch of rockstars that were teaching me at the time, so I got very, very lucky in all of my professors. At the time I just wanted to do some hip-hop and architecture stuff. I just wanted to do something really cool and be done with it and I had a professor who just made a comment that race and architecture have nothing to do with each other.

Amy: Oh, fuck that.

Germane: Yeah, and so everything about me is pushing back against what I feel like unjust circumstances. I was like, alright, time to shift the project and just do this instead and come up with this project around public housing and social and problematic resources that are typically not afforded to people of color, and this idea of nimbyism, of absolutely you can do this, just not in my neighborhood. So, I did a very speculative proposal…and I’m not having good pinups and reviews with the juries because they are like, this is racist, etc. I am just like, one, I am black, I can’t be racist. I don’t have institutional power to inflict any type of unfortunate circumstances on you, like I can be prejudiced, I can be a bigot but I can’t be racist just by definition. So, these things just aren’t going well and the whole time Jennifer is like, “Germane, if you are not pissing people off, you are not doing your project correctly.” And they fly in, this guy from Brazil for our mid review. I will never forget it because I am struggling so bad with the project, I don’t know what to do. I wrote an email to Milton Curry; he was teaching at the University of Michigan at the time. Didn’t know me from a door knob. I was like, “Hey, I’m doing this project. I don’t know anybody that is black that is an architect because I still don’t have a professor yet that is black, so I write to him and he is like, “You know what, this is too much for an email, call me.” I am just like, wow, so I have a full conversation with him about the stuff and then same thing with Craig Wilkins because he is also at Michigan, so I write him. He called me so I talked to him as well and this is what I like to do, each time a student writes me, I write back because I was that student. So, all that stuff works out and the guy shows me this project called The Robots of Brixton, and everything just clicked in my head at that moment, this is the guy from Brazil. I take off, I do the thesis proposal, I make this huge model, I make the drawings and I made a newspaper. The newspaper is, I think, what won me the prize because I wrote every single article and it was based off comments I got during my reviews, while I was sort of cheeky, poking fun at the jurors of saying, “This is like not in my backyard.” Full article about housing and development. ‘That will cost too much’ full article about economy, and then I had this little article called, ‘A conversation with the architect’ of me saying, you guys clearly don’t want to give me the crit that I want, I will just interview myself. There was like a whole fake interview I did with the architect of myself and I gave that newspaper to all the jurors. There are pictures on Woodbury’s page too of Barbara sitting there with a newspaper in her hand and she is like reading the thing. I won the thesis prize and the professor who said, “Race and architecture don’t match.” Pulled him to the side and said, “Hey, you have something here. This might be the start of your career.” So, even they realized sort of the error.

Amy: Yeah. Yeah. Okay, so there is so much that I love about this and I will just say first of all, your particular style of rebellion is so creative and awesome because…

Germane: Thank you.

Amy: You were angry clearly, and you were needing to piss them off and prove them wrong, but you did so in such a way that actually pointed out all of the absurdities and incongruencies and hypocrisies that were, you know, and you also gave yourself a voice by interviewing yourself and getting to say what you wanted to say. By putting it in the printed format, the newspaper, you allowed everybody to digest it and not have to defend themselves in the moment, so they could actually come back to you and say, “you know what, you are right, I was wrong.” Everything about that feels to me like somebody who understand the dynamics and how to get through in a really creative and productive way that doesn’t compromise your voice or your values.

Germane: I put myself on a schedule again. This goes back to the basketball thing. I would tell myself from 9am until 12am, I will work in the studio every single day because then my thesis system I only had one class and that was my thesis studio. I spent every single day during this time so I can still go to bed at a reasonable time, get some sleep, but the last two hours of the day I would just write these articles and they started as frustration, it was just, ‘I’ve got to get these thoughts out of my head.’ This would go back to basketball stuff because if my coach got mad at me, then I couldn’t curse back at my coach because then I am not going to play, so I had to learn how to channel all the anger I would get from whatever things he might have said. I am like, ‘You’re not right, man. That wasn’t my defensive assignment, he messed that up. Why are you yelling at me?” But I can’t say that because if I say that, I am on the bench. I can’t do it. So I had to find other ways to do it, so I would circumvent it by whatever and when the game was over he would be like, “I knew you weren’t the one that was the problem but I know I can yell at you and it’s okay. I can’t yell at him.” I’m just like, whatever man. We will just go on and do whatever and go that way.

Amy: So, this is sportsmanship?

Germane: Absolutely.

Amy: We’ve covered your formative years in detail but your career is also incredibly exciting and I sort of ran through some of your accomplishments in the intro so that the audience is familiar with what a big deal you are.

Germane: (Laughter)

Amy: I would love for you to maybe take us through your career trajectory, stop on some of the highlights and kind of illustrate your creative process along the way, as I was doing research, some of the projects that really stood out to me are obviously the founding of your own studio but Sacred Stoops and obviously the sixth column order and the whole Rome prize deal, so?

Germane: So, when I finished the thesis and this is, I am not totally finished. It is maybe a couple of weeks before the semester is over and my professor, Jennifer Bonner, says, “Hey, I need to have a meeting with you.” Then my secondary advisor was a gentleman named Christian Stayner. Christian is like one of the smartest people I have ever met. He was our theory professor and they were like, ‘we’ve been teaming up on proposals, we keep losing but we made it to the second round of this one in this small city called Opa-Locka in South Florida and we would love for you to be on our team.” I was like, ‘I am not done with the semester yet but sure.’ They were like, “We’d also like for you to pitch the project.” I go, “What?” They are like, “Yeah, you’re really good at talking” and saying things like, “We think we lose because we are not good at presenting, so we are thinking maybe you can come up with the stuff that we should say and then we have a better chance of doing it.” So, we talk about the work and like cool, we’ll do it. We fly to Miami. On the plane I come up with the full pitch and I am like, I need to live there because people aren’t going to believe you if you don’t have like a foot in the community. So, we do the pitch and at the end of the pitch I like drop the bombshell, like, oh yeah, and I’m going to move here. They are like, “Wait. What?” Like yeah, we can’t do this work if somebody doesn’t live here. We are not about just dropping off art and leaving. I am going to be here. I am going to live in the neighborhood, and we end up winning the proposal and when we do that, we don’t know we’ve won yet. So, I go back to LA and I am working in an architecture office, which is like a collaborative office with Francois Perrin, another one of my former professors who passed away unexpectedly and then Catherine Garrison, who is an architect. She actually used to work with Barbara and stuff, so again weird sort of connections. I am doing design installations with Francois. I am doing Capital A Architecture with Catherine. So, I am split back and forth between the two and that is literally how my practice, everybody calls my practice experimental. I am like, it’s really not. This is literally what I was doing when I was working between two offices. I just do it all in-house now as opposed to between two people. The first project we worked on for Francois was at the Richard Neutra House in Los Feliz. Yeah, so I spent the entire summer at the VLD house, working with acclaimed visual artist Xavier Veilhan, who has like a sculpture in front of MoMA. He has work in front of the center of Pompidou. He is like one of the most famous visual artists in the world. That was my boss for an entire summer.

Amy: Wow!

Germane: It was insane that I got to work with a world-class artist. It was amazing and then I did that and then when that finished, we found out that we won the proposal in Miami. At this point, Francois is like, “Hey Germane, you should move to Paris and work in Jean Nouvel’s office.” He was like, “Jean Nouvel is my good friend. I can get you a job there. You speak French, this can work.” So, I was, cool, this could work, but then we find out we win and I am like, wait a minute. I got to choose between moving to Miami or moving to Paris and my parents are obviously going to pick Paris, right, like, we didn’t put you in these programs for all this time for nothing, we will see you when you come back. I choose Miami and they are like, what are you doing? I am like, well, if I go there, I am working for him. I might never get my name on anything. If I take this job, I am betting on myself and this is our project. So, if it works, this can be the start of something great. If it doesn’t work, well at least I bet on myself and I took a chance. That is how I ended up in South Florida and then everything took off.

Amy: Yeah! Like a rocket! (Laughs)

Germane: Yeah, everything took off from there.

Amy: And you are still in Miami, so that was a good choice to move there. I love that this story starts with you taking a bet on yourself. I just want to underscore that because anybody who is listening to this, who might be a young creative, I really feel like that is an important decision you made. You invested in yourself and you believed in your creativity and then you put that energy and effort into it that it required. Okay, so talk to me about how it takes off. So, I moved to Opa-Locka, full name Opa-Tisha-Wocka-Locka, Florida, so it’s a real place. It's a Seminole name but it’s in Miami-Dade. Historically black neighborhood, largest collection of Moorish Revival architecture in the western hemisphere. So I moved there, we're doing work, and after the first year Jennifer and Christian leave the project and they leave the project because there's a bunch of underhanded things happening behind the scenes that just weren't cool that was happening. We can't keep investing resources into this, we have to depart the project. Meanwhile I moved there so I can't just leave. I'm here, people in the neighborhood know me now, I've met all these people, I've made community with them so I stayed. When I stayed, a year later we got a huge grant and the CEO was like, “Hey, you stuck around, do you still want to make these projects happen?” I’m like “Hell yeah!” At this point we're starting and I apply for, well I don't apply, I get nominated for a Curbed Young Gun Award. Curbed.com architecture resource or whatever, and it was people that were under 30 that were doing non-conventional work in the built environment and they submitted my work that was happening in Opa-locka. And I win! So I am one of the Young Guns in the class of 2015 and they do a full photo spread and stuff. It's like look at this kid who is under 30 doing all this work in his neighborhood, trying to redevelop it after gentrification. That's when my name gets on the radar. Okay, I'm here, I'm 29, I'm doing this stuff way faster than we typically do. Then at this point people are starting to read Curbed, they're saying my name, they're writing me for interviews and things. I'm just ignoring all of it. I'm just trying to get this work done. I'm not actually trying to capitalize on any of this. Then we get a new dean at the University of Miami, Dean Rodolphe el-Khoury.

Amy: And you've begun teaching there already?

Germane: Yeah, I started teaching my first year there in Miami. This is under Liz Zeiberg so she hires me and then the new dean comes in and he's like, “Hey, I see a lot of potential. I'm a nominator for MOMA PS1, would you like to be nominated for a MOMA POS1?” Absolutely. That's what some people dream about. But I don't get it. I lose. I'm not even a finalist for it.

Amy: That's a nice vote of confidence from the new dean.

Germane: Absolutely. And it's a bi-annual thing so he gets another one two years later and he's like, “Do you want to be submitted again?” Absolutely! Now at this point I'm a full-time professor, it's 2016, the Opa-Locka stuff has been built, things are all happening. I decide I've got to go out on my own now. I've been here for four years; I need to see what it's like being by myself. I'll figure this out. So I do it and I write the Sacred Stoops proposal to the Grant Foundation. Which is I know porches, I know the south, I know what it means to be in the space. I don't know if you all care about this but this is what I know so I'm going to just write this and if I get it, I get it, if I don't maybe it's just not meant for me to do this whole research thing because my priorities aren't the same as your priorities. But I get it. And the moment I get it four emails come in in less than 48 hours. One from the Swiss Institute in New York, one from Princeton to do a lecture, one from the New York Times to send a reported to follow me around, and I forget where the fourth one was from. I haven't even done anything yet; I just started the research now. The New York Time was like, “Yeah but we want to send somebody with you.” So they sent a reporter with me to go around Detroit looking at porches and talking to people and interviewing and stuff.

Amy: I was born and raised in Ypsilanti.

Germane: I have a lot of family in Detroit so that's why I'm going there.

Amy: I love that area; I miss it so much.

Germane: Yeah. So we did a whole thing. It was a whole piece they did. They followed me around and stuff and then there is a gentleman who runs the Humanities in Place Department at the Mellon Foundation named Justin Garrett Moore and Justin had been following my work since the early Curbed article and I never knew it. When he was following it he invited me to come do to a talk at this Spaces and Place Conference, sort of an unofficial planning conference that was always attached to the planning conference to get more diverse people into the space. He's like, “You, I love the work you do, it's super grass-roots, it's actually community focused.” And it's like, 'how do you know me?' And he's like, “I saw the Curbed Young Gun Article, I've been following you ever since.” I was like, “Wait, really?” He was like, “Yeah, I'm always intrigued by people who are actually out doing the work and not just talking about it theoretically. You're out doing it.” I was like, “Oh thanks man.” I kind of just left it at that and then the next thing I know I get the email from MOMA saying, “We're doing the first ever all black architecture exhibition, we would love for you to be a part of it.” So I asked the leadership. I said, “How did you all find me?” Because these people, I know how you find these people, these are all huge names. I'm the youngest here. I'm probably the least known out of all these people. They all have relationships. Nobody knows me. How did you find me? They were like, “Oh you applied to MOMA PS1 a couple of years ago.” Wait, what? They were like, “Yeah, we loved your proposal, we just didn't think it matched for PS1 so we just put your portfolio to the side.” Hold on, wait a minute. They're like, “Yeah, your porch one, right?” I was like, “Wow.” I thought that was just an exercise in futility but actually they held onto it and that's how I got put in.

Amy: That's why I tell all my students to always submit to everything because people do. It does register on people's brains and they remember you. Yeah, okay. That's awesome.

Germane: That's how MOMA happens.

Amy: Not only is the exhibition a huge deal and it's the first of its kind for MOMA, but you're a founding member of the Black Reconstruction Collective that was founded from the other participants in that exhibition. That sounds like a lot of energy coalesced to make something bigger.

Germane: The bigger issue for us was we're not special, us 10. There are so many other black designers and architects, we were just the ones that were chosen. So how do we make sure that those people understand that we're not better than anybody. We're not special, so how can we make the platform even bigger and that's why we started the BRC to sort of do that and we've been doing that for two years now and fulfilling that promise. The biggest thing was because I was so young compared to the people in the show I have to deliver. I'm afraid that if I don't do this...

Amy: Yeah, I was going to ask you how you're handling the pressure.

Germane: Oh man, it was a lot. I came out the gate super bold. I told the curatorial team I'm not making a single architectural drawing. They were like, 'you know this is an architecture show, right?' I do. I'm not doing it though. They were like, 'why?' Because this is still a museum and I want everybody to engage with it and everybody doesn't know how to read a plan. So I'm not going to do that. I would rather just build something and do some collages and be done with it. They were like, 'all right, Germane, whatever.' Then I did it and they were like, 'okay so we're going to use these as all of our press images.' So it became (laughter) all the press stuff. It was crazy when I went to MOMA and you see Basquiat fourth floor, you see Pope.L fifth floor, and then you see my image that is right there.

Amy: Germane Barnes.

Germane: Yeah. I'm just like, 'wow, that's insane.'

Amy: Wow.

Germane: I guess I nailed it because then everybody started coming and asking for follow ups and things and then Rome Prize happens after that.

Amy: This is 2021, this is an incredible year and I just want to tell people the name of that work was A Spectrum of Blackness and I want to say that so that they can Google it properly. You also won the Harvard GSD Wheelwright Prize that year, right? (Laughs)

Germane: It was... (Laughs)

Amy: Hot damn, Germane!

Germane: Some might say I peaked. (Laughter)

Amy: No, no, no, no, no. No, you're just getting started. The Rome Prize, how did that hit when you won that because that is a huge deal and congratulations.

Germane: Thank you. I'll be totally honest (laughs) with you. This is Covid times it's happening and I'm a bit of a loner in that I enjoy just being by myself. It's something that goes with me having a huge family and rarely getting time to myself so I cherish it when I do and so in my mind it was a chance for me to buckle down and get all the work done that I've been trying to get done and just focus. Cool, this is my off-season training, I'm going to get everything out. And I get an email from the American Academy of Rome saying, “You've been nominated as someone who will be right for this fellowship, you should apply.” I'm like, 'I don't do anything around classical architecture.' Who would put me up for this? It doesn't make any sense. And I think somebody was just saying, 'here's some black architects, you guys should go ahead and put a name on the list.' So I do it. I don't even know what to propose but then I think back to my porch research and I think back to a conversation I had with a colleague who said that the Romans had portraits first but they were porticoes. Oh, I can do a contested history of porches and porticoes. That's what I can put forth in my proposal so it has a lens into North African or diaspora contributions to classical architecture.

Amy: Yeah, fascinating.

Germane: I put all this together as a proposal and at the end my stupid ass says, “I'm going to design a new column order.” (Laughter) I don't know why I said that, but again sometimes I say things and I'll figure it out later. (Laughs) So I write it in there and when this happens I'm like, 'all right, I think this is a really good proposal, I'm going to also apply to the GSD Wheelwright Prize because they're due around the same time.' Oh, and Creative Capital is also due around the same time. It just so happened they were all due. I'm like, 'one of these people are going to give me money, this is a good proposal.' One of the three should give me money because this isn't bad. So I send it to all three and I get letters back from all three and Rome Prize is like, 'you have an interview on this date.' GSD says, “You're a finalist, you have an interview on this date.” Creative Capital just says, “You've won.” So I'm just like, 'okay, so I got one, if the other two don't go well, I'm good.' I have still got the money from Creative Capital; I can make this happen. I do the Rome Prize interview and true story, Amy, they say to me, “What would this do for your career and how would you respond if you win the Rome Prize?” I go, “Oh, I'll probably just curse a lot.” (Laughter) Huh? “Oh yeah, yeah, I'll get a phone call probably like 4 pm,” because the guy who was doing all the organizing would always call at 4 o'clock for some reason. “He'll probably call at 4 o'clock, I'll probably curse and yell and be like, 'thank you,' and then be on the first plane to Italy.” They all laughed and they were like, 'okay.' End of the call.

That was a Wednesday. The very next day, that Thursday I get a call at 4 o'clock. (Laughter). He's like, “Germane, we would like to offer you the Rome Prize.” (Laughter) So I laugh and I start cursing and I say yes and then he goes, “The jury made sure I called you at 4 o'clock.” (Laughter) Perfect. Great, that was a great touch. So I finished that and man, I'm two for three. There's no way in hell I'm going to get the GSD Wheelwright Prize, too. But two out of three is insane. Nobody ever wins these awards so you might win one. I've gotten them all already, so cool. I don't need Wheelwright, if I get it, I get it. I do the talk and when the talk is over and this goes against some of the basketball stuff, I can read energies. I'm like, 'I think I just won the Wheelwright Prize.' The moment the interview was over I think I just won. I have no idea who else they've picked but I don't think it went as well as mine just went. I have this thing where I know, if people start projecting what I can do without me saying anything, I'm like, 'oh I got it then.' If you're already figuring out how to fit me in here because I didn't say any of that, you came up with that. I'm good. I've won this. And then like a week later I get a phone call from Sarah Whiting. She's the dean at the GSD. She's like, “Hi, Germane.” Hey. She's like, “So you know what this call is about.” I'm like, “I won?” She's like, “You won.” At this point what the hell? I got Rome Prize, I got GSD, I got this, I got this. And then I end up getting US Artist Award and the Architecture League Prize of New York. I swept every young architects award. I literally can't win anything else but a Pritzker and a Genius Award. That's literally all that's left.

Amy: Now you just put that in the universe. I wonder when, what year...

Germane: I'm working towards it.

Amy: Okay, so how does this not fuck with your head? How do you not get...

Germane: It does.

Amy: Okay.

Germane: It does.

Amy: So what do you do about that?

Germane: It does. I play a lot of basketball, Amy. (Laughter)

Amy: Right.

Germane: Hey, I play a lot of fucking basketball. That is how I do it. Then all these things are happening and I have to deliver. There again it goes back to my sports mind of 'this is the pressure.' If you're Michael Jordan, if you're LeBron James, if you're one of these people who want to be the best, you have to accept the pressure. You can't run from it. You can't say, “Don't put me in the moments that put all the eyes on me.” MOMA was like my first chance in the all-star game and I held my own with the other greats. Then Rome Prize, American Academy was my second opportunity. All right, I've nailed this. Then I get the email from Leslie Loco to be in the 2023 Venice Biennale. Wait a minute. Wait, what? Yeah. I get this email when I'm in Sicily doing my research for the stuff for the Rome Prize and I'm like, 'this is insane.' I'm not a part of the American Pavilion. I'm literally getting an invitation from Leslie herself in Arsenale and that is the NBA finals. All right, more pressure, let's go.

Amy: Okay, that's coming up, right? That's still...

Germane: That is in a month.

Amy: How are you doing? (Laughs)

Germane: We're done with everything except for a few artifacts that I'll be taking on a plane with me. But I'm not sure if you saw the list and everything about where people are placed but they got me in the first damn room. Imagine my young ass in there with titans of architecture and the first thing they see is me. That's fun.

Amy: That is. You know what happens to rockstars when they get famous too fast?

Germane: Yeah, it doesn't go well.

Amy: (Laughter) What's going to happen to you?

Germane: It doesn't go well. So yeah.

Amy: Basketball is your only mechanism of keeping yourself in check?

Germane: Yeah, basketball. I watch it. I play it. I listen to podcasts. People will tell you I probably absorb too much of it. But the biggest thing like I said earlier in the call, there's the people who touch the stove and those that listen. People tell me stuff, I listen, so I've been able to dodge a lot of the normal pitfalls that have happened. Then I always tell people I'm not famous. Architecture famous doesn't count. (Laughter) They wouldn't let me in. It doesn't matter but this one profession knows who I am. The rest of the world has no clue. But you can't tell that to my niece. My niece swears I'm famous. I'm like, “I'm really not, baby girl.” (Laughter)

Amy: I mean I'm excited that your work is being celebrated in all of these different venues. Because I do think what you're doing is important and powerful and compelling. And it's also... I want to say you're expanding the canon. You're sort of changing the canon. You're inviting everybody to approach architecture in the built world from a more, to question their own perspective and to approach it from a new perspective. You're almost writing the recipe for that so that other people can do it as well. You're not claiming ownership necessarily. So much as filtering it through your own creative process and generating really compelling artifacts and projects and installation art and built projects from that. I'm just very excited that you are having an impact on the built world. And I can't wait to see how this progresses throughout your career. I hope you never lose your passion. I want to ask you before we get off the phone in terms of yourself, your personal life, obviously you're enjoying your career and you're playing basketball. It sounds like you've got a lot of good people in your support network.

Germane: Absolutely.

Amy: But in terms of crafting your own beautiful life and impactful legacy, where and what do you need to put more energy into in the future? What needs filling out and what needs pruning back?

Germane: That is a great question and probably a great way to cap off the call. I recently started therapy again. Not because anything bad is happening, but just because there's a lot of shit going on in my life and I'm just trying to figure out how to manage things and manage relationships. I'm a tenured professor which is insane for a 27 year old to say out loud. I did it in two and a half years. Nope, I'm not waiting, I'll just go up now. I'm the director of our graduate program, so I am one of the few black directors of the School of Architecture in the country.

Amy: Congratulations, that's amazing.

Germane: I have a lot of things that are going on, I need to figure out how to manage this stuff so I started seeing a therapist a few months ago. A lot of it is about me being present in relationships because oftentimes I think me being physically there is me being present but it's not. So because I've sort of had this insatiable desire to be the best in architecture, I've missed a lot of things. I've missed some of my niece's birthdays. I've missed some of my parents' birthdays or parties or gatherings because everybody lives in Chicago but me. I had to learn what are my priorities. What are the things that matter. Then recently my grandmother has been a bit sick so we all flew home to go see her and there were so many people that were there and I just didn't realize how many people she had touched. The whole time I'm sitting there I'm just putting things into perspective. If I don't create or carve out time for this part of my life then who am I doing this for? What is all the success for? So I've been able to reorient to a lot of those priorities which again is why the therapist has been very helpful in that regard. I think a lot of people just assume therapy means there's a crisis. No. I have nothing to complain about. My life is breeze.

Amy: No, it's an oil-change. It's tune-up.

Germane: Yeah, my life is an absolute breeze. I just do this because I think it's good for maintenance. He's been trying to help me to make sure that people feel valued, and so I'm able to see the value in platonic relationships, romantic relationships, and be able to re-prioritize things. I've been trying to do better at that lately to make room for people and make room outside of 'I've got this project that is coming up,' or 'I've got to do this,' or 'my momentum is still going, I don't want to lose that momentum and fall out of the public eye,' and keep taking on every opportunity. Because sometimes every opportunity isn't the right opportunity. So hopefully that continues, but I'm trying to do better.

Amy: Well I hope you get all the opportunities that you want. I do want to say that you were very present during this interview. And I really appreciate you sharing your whole story with me and our listeners. I just hope I get a chance to meet you in person one day because...

Germane: Likewise. This was very fun.

Amy: Hey, thanks so much for listening. For a transcript of this episode, and more about Germane, including images of his work, and a bonus Q&A - head to cleverpodcast.com. If you can think of 3 people who would be inspired by Clever - please tell them! It really means a lot to us when you share Clever with your friends. You can listen to Clever on any of the podcast apps - please do hit the Follow or subscribe button in your app of choice so our new episodes will turn up in your feed. We love to hear from you on LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter - you can find us @cleverpodcast and you can find me @amydevers. Please stay tuned for upcoming announcements and bonus content. You can subscribe to our newsletter at cleverpodcast.com to make sure you don’t miss anythingClever is hosted & produced by me, Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever is a proud member of the Surround podcast network. Visit surroundpodcasts.com to discover more of the Architecture and Design industry’s premier shows.

Germane playing basketball

Germane during his thesis

Germane and friends from The Community, Housing & Identity Lab (CHIL) at the University of Miami, School of Architecture

Pop Up Porch

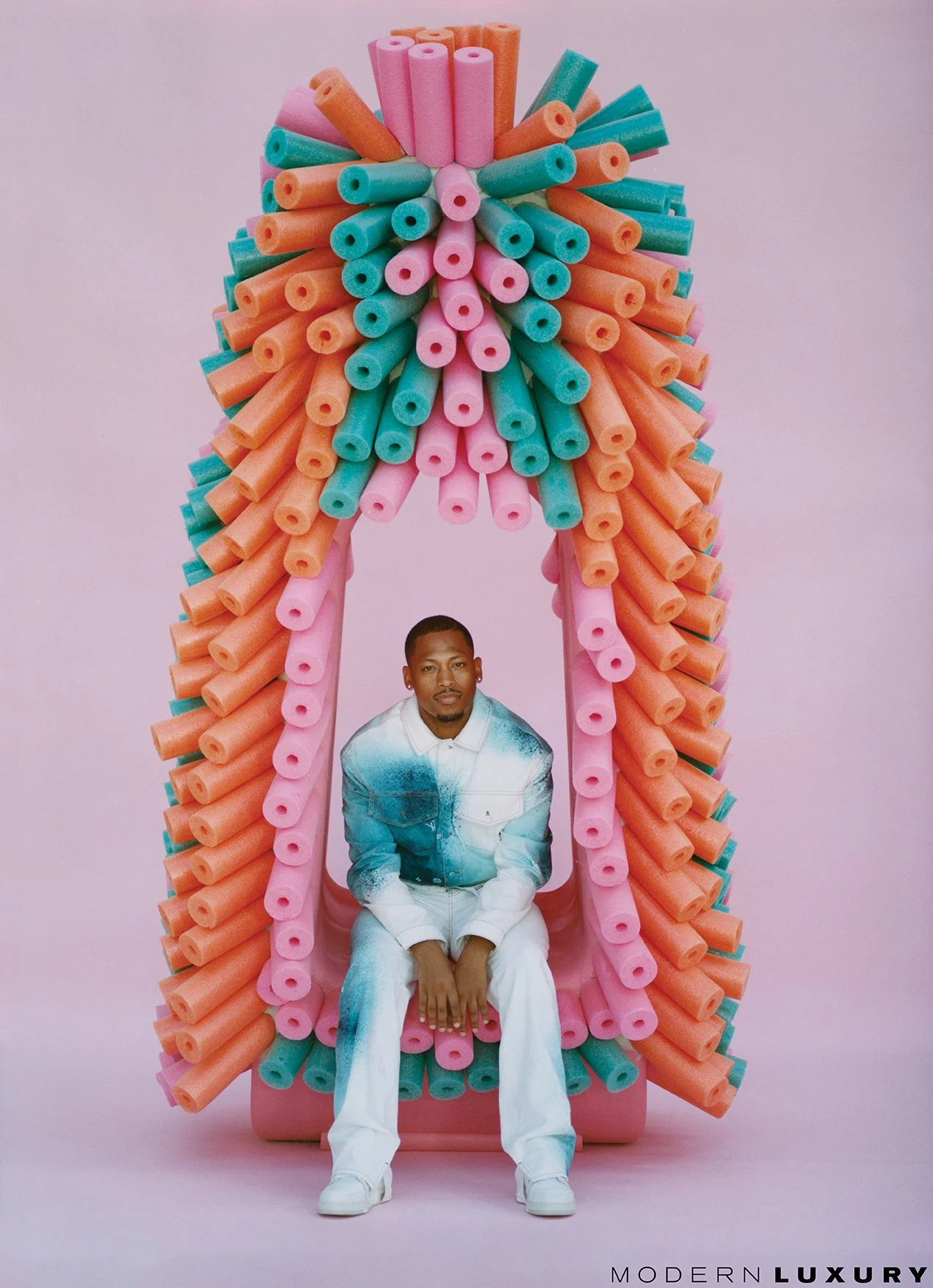

Germane Barnes in Miami Magazine, Photo by Josh Aaronson

Rome Prize Open Studios

Uneasy Lies the Head that Wears a Crown. Photo by Blair Reid Jr

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.