Ep. 191: Rodolfo Agrella Uses Laughter as a Powerful Design Tool

Multidisciplinary designer, Rodolfo Agrella, grew up in Venezuela with a happy place at a kid-sized table. A self-described weirdo and excellent dancer, he put it all to work as a social butterfly. Now at the helm of an award-winning studio designing products, interiors and experiences, he’s on a steady and colorful streak translating the vibrancy of the tropics into a universal design language.

-

Amy: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to Rodolfo Agrella. He is founder and Design Director of the New york-based Rodolfo Agrella Design Studios – which describes itself like this:“We are an assembly of energies and unique talents working together to manifest narratives into joyful award-winning experiences – generating exciting interiors, graphics, digital, phygital and physical products, immersive spaces and exhibitions.” And while all of that is totally accurate - I just want to personally endorse the JOYFUL part. Born and raised in Venezuela, he studied architecture in Italy at the Politecnico di Milano. After founding and leading a design studio in Caracas for over 5 years, he transitioned to New York City on a whim, and was the Design Lead at WeWork for a stint before founding his own studio in 2015. Now he’s frequently called out as one the leading voices of the next generation of Latin American designers. And Rodolfo himself says that one of his proudest accomplishments is translating the spirit of Venezuela into an international language. This NY Design week 2023 he’s unveiling a new immersive experience he designed in collaboration with Heller Furniture. And if you’ll be attending ICFF + WantedDesign, you will see Rodolfo’s work, and joy, all throughout the show - in the Oasis, the Talks Stage, the new Restaurant, and the Wanted Design Manhattan lounge and cafe! His vibrancy is buoyant and his laugh will f’ing make your day - here’s Rodolfo…

Rodolfo: My name is Rodolfo Agrella. I live in New York. I am the founder and director of the Rodolfo Agrella Design Studio, and we are a studio devoted to creating beautiful things, beautiful experiences, and I love it.

Amy: You do love it. I can tell because your exuberance comes through in everything you do and all the ways you talk about it. (Laughter) Let me understand where all that love comes from.

Rodolfo: I am originally from Caracas, Venezuela. I'm the youngest of four. My family is a huge family, the typical Latin family. I grew up in this amazing group of people, very diverse. Being always a little bit like the weirdo.I have two brothers and a sister and all of them are very sporty. They are older than me and I was always the sentimental, the emotional, the artist of the family let's say. My parents knew that and my family knew that. I was recently talking to my mom and asking her why ever Christmas I didn't receive toys like a bike or something. Everything was just markers and things to do arts and crafts because I was always creating stuff. Always. Actually the first thing that I ever got was a small table. It was my size when I was a kid and in that little table I was able to do everything that I wanted. I was just there. That was my world. That was basically my first studio. (Laughs)

Amy: That's amazing. I also am so fascinated with children's furniture because it allows you as a child to sort of make believe that the world fits you and you're not this small person in this big world.

Rodolfo: I always remember that little table as a very special one. Listen, it's not that far what I'm doing right now. I was just playing with color, having fun, and just creating these little worlds for me. Now I do it for everybody. (Laughter)

Amy: Yes. It sounds like your family was very supportive of this and even though you were the weirdo in the family, it was still loved and celebrated as opposed to trying to get you to conform.

Rodolfo: No, absolutely. For a few years my family live in Valencia which is a city close by to Caracas and we had no attachment to Valencia whatsoever. My mom used to go to Caracas just to buy food. Every Friday my dad would pick up all of us at school and then just go to Caracas for the weekend to visit the family, my cousins, my aunts, everybody. Also to go to museums and to have a little bit of cultural influence in a way. Valencia at that time was a small town. All my brothers and sisters would just go out with my cousins, I was the one going to the museum or to the theater with my aunts, my uncles.

It was a lovely time and all of that influences big time on what I do and who I am. Fun fact is that every Monday at school at the beginning, early in the morning teachers will ask, “Guys, what did you do over the weekend?” My friends were like, 'I was playing soccer,' or,' we went to the club,' or whatever. Right? I was like, “I went to the opera and saw La Boheme or Madame Butterfly,” when I was like eight or 10 years. (Laughter) That was crazy. Crazy. So since then I feel like a weirdo and I love it.

Amy: (Laughter) You have embraced it, yes.

Rodolfo: Yes. Since very little.

Amy: It sounds kind of idyllic honestly. You have this support in terms of developing your creativity, being in your own little world, playing with color. You were given not only the physical support in terms of the art supplies and the table, but the emotional support in terms of your parents understanding and nurturing this in you.

Rodolfo: Even sometimes they didn't understand, but they were just like, 'okay you do you. (Laughter) We don't get what you're doing.' Even after I started school and I went to the university it's like, 'we really don't get what you do, but we support you, we're very proud of you.' That's amazing. That's really, really amazing.

Amy: Both your parents still alive?

Rodolfo: My dad passed away like 12 years ago, but my mom is alive and she's celebrating every step of my career. Yeah.

Amy: Nobody gets through the teenage years without a little something, a little awkwardness, a little angst, some sort of identity crisis. What was yours?

Rodolfo: Well. (Laughter) Well where should we start? I've always considered myself a social butterfly. At school I was known for two reasons. One, my brothers and my sister, they were way older than me. I have a difference with my oldest brother of 11 years and they were sort of popular at school. I was the little brother, so in order to get to them they have to pass through me. So (laughs) it was a small school so everybody knew each other. But in the other side I was kind of a nerd because I was always with good grades and friends with the teachers and friends with everybody.

You know that in Latin America the Quincenera thing is a thing so all of these girls were throwing these huge parties and I am a very good dancer (laughter) just FYI. Even if I was in a lower grade or whatever they would invite me to dance with them. In a way it was like the nerdy guy that was cool to invite to their parties because he was just fun and he could dance. And this laugh that I have, it's just you know. People would invite me there back then just because of your laugh. Now I realize the power of it.

Amy: It's almost like the audio version of a lighthouse. It cuts through everything and is like a beacon of joy (laughter) through all the fog and noise. That laugh, like...

Rodolfo: That's the best description I've ever heard about that. (Laughter) Amy, that's amazing. Thank you very much for that image. I love it. I'm going to use it.

Amy: Did you have this self-awareness when you were younger as well? Were you comfortable being a nerdy, good dancer?

Rodolfo: I was comfortable dancing. Up to a certain extent. There was this time in my life that I just wanted to be a dancer. But back then in Caracas there were no schools devoted to that so I decided I'm going to study architecture. There was no self-awareness of that. I realized that I was good recently. In my early 20s I would say. I realized that is something special that I need to keep adding energy to that and focusing on that. In a way focusing that laser beam and using it for a bigger purpose. I'm getting a little bit esoteric if you will, but that is something that I really, really think is part of my essence and what makes me be who I am and be different than anybody. Not just me, the people that work with me, the people that I collaborate with, all of those weird stuff and nerdy things from my past are what makes me be me.

Amy: It's like the special spice combination that gives you your particular flavor.

Rodolfo: Yes. Yes. Yes. Plus, obviously I'm from the tropics (laughter) so everything goes there in abundance. Color is abundance, people are loud, and I'm part of that, too.

Amy: Yes, that's the ecosystem you were grown in.

Rodolfo: Yes.

Amy: What I need help understanding is how you got to architecture because to me that seems very disciplined, stiff, and orderly. We all know that architecture is really important to the built world obviously, but it's very hard to get a project built. There's so much work that is conceptual and abstract that never actually becomes a built project. Talk to me about your decision to study architecture and then your trajectory through your journey as a student.

Rodolfo: Well I decided to study architecture for one simple reason, I wasn't aware really. I was 16, 16 when I entered the university. I was a kid and I decided to. I had good grades so I was able to enter any university. But then the main reason was at that time we were living in Valencia and I really wanted to study in Caracas.

Amy: (Laughs) You just wanted to get to the city.

Rodolfo: My sister was studying medicine, my other brother was studying economy, and then this other brother was studying civil engineering and everybody was like, 'no you should study civil engineering because you can build stuff with that, or you should be a graphic designer or you should study art or something.' And in one of these meetings and lectures about careers and stuff like that I heard that an architect could do anything. I was like, 'bingo, that's me.' I'm going to go that way.

So I presented that and I moved to Caracas and I started to study architecture at the Central University of Caracas which is a marvel of the mid-century modern. Caracas in general is all built out of this incredible sense of the men of the future seen from the 50s. So the Central University was basically a playground for the architect, Carlos Raul Villanueva to do all of these crazy shapes. It was very avant-garde piece of architecture for that period of time. We were basically in the 50s with Venezuela was Dubai. So I started there. The faculty we have six colors, I believe so. The whole university is just covered up with these amazing art pieces dialoguing with the architecture. It's incredible.

We have…it's a lot of things, a lot of things. So in the very first day of school I saw myself doing something like that. I wasn't aware of what it was or anything, just I think I can do this. Then through my teachers, teachers are an amazing thing, and I remember my first semester teacher that she saw one of my sketches once and she was like, 'you have a lot of intuition, you just need to be a little bit more disciplined.' I took that very seriously because this is the thing, I can be a creative but I'm also very disciplined in what I do. There is a lot of rigorosity in what I do, and I suffer from OCDs big time. So once I get the laser beam, if I put the laser targeting something, I'm going to make it happen no matter what. That's always related to a discipline thing. Discipline and great ideas are a perfect match because if you have just a great idea but you don't have the discipline to manifest that, just getting it down into this great thing and how it gets translated into the physical world. So I was able to learn that in the very early stage of school. And this same teacher she sent me an email once. “The faculty has these scholarships to go to Europe to study to end up your career there.” That's how I ended up in Milan. Studied at the Politecnico di Milano.

Amy: Oh, did you get nominated by faculty because they saw you as a special star student and they wanted to support you?

Rodolfo: Yes. Exactly. I was like, 'why Milan?' Well because the take on architecture here in Milan, it's more related to what I really wanted to do. At that time mid of my career, of my student career I realized yes I want to be an architect but I enjoy also designing the details of the architecture. I enjoy also selecting the colors of how these things are going to look. And this teacher, Anna-Maria Marine, told me I have to go to the Politecnico because they have a very specific take on what the work of an architect is. Italy in general has that.

Amy: More holistic.

Rodolfo: Yes.

Amy: For context, what year are we in when you go to Politecnico?

Rodolfo: That was 2004. It was crazy because that was the first time that I would have a trip to the exterior in every sense.

Amy: So you'd never been outside of the country?

Rodolfo: No.

Amy: Did you speak Italian?

Rodolfo: A little bit because at the Central University in Caracas they have these lessons. They give you a month of lessons. The only thing that I could say was ciao, si, no, because it's almost the same things as in Spanish. (Laughter) But fortunately the Politecnico had this amazing program that they receive the students and they basically hold your hand at the very beginning and guide you through the Italian culture and then you do you. It was really incredible. That first semester, as the beginning I was complaining because we are in Venezuela and we didn't have access to a lot of things. You're comparing yourself to European students, to American students. I had a little bit of that stigma of this guy from the third world. At some point I remember a person that asked me, “Where did you get those clothes that you're wearing?” And I was like, “I don't remember, it was H&M or Zara or something like that.” “No, no, no. Did you get it here?” Because they have this image of Venezuela that is just the innocence. He thought that I was an indigenous person that will come here and was like 'I need to change this.' I really need to change this. Fun fact is that the first semester that I was studying these are big rooms of like 120 students per class and Geno Tucci which is a famous architect here saw my project and said, “Hey wait, this is not eighth semester, we are on sixth semester here,” fifth of sixth. I was like, 'no, no, no, this is my year, the fifth or sixth, I don't remember. He was like, “But why do you draw everything so good? So precise. Why does your building have beams?” And I was like, 'Because you need to.” (Laughter)

Amy: Otherwise it won't stand up.

Rodolfo: Yes. And in that sense we were very technical in Venezuela. That was the gateway to working with Geno Tucci. After this on Monday he was looking for an intern, everybody was dying to get that intern position and I didn't know who he was to be honest. I knew that he was known here but not that known. So when I got that Monday into the studio and I saw that, I was like okay I can do this. (Laughs) But it was also celebrating what I learned back in Caracas.

Amy: Yeah. This sounds like actually not just you being selected because you are an exemplary student, but also somebody who recognizes that the blending of your Latin American flavor plus your studies with their Italian mindset and their practice could be a good thing.

Rodolfo: Yes. Absolutely. A celebration of that melting pot because it provides an international flair to everything. Obviously my approach to color and the way I see things, it's just not me. Everybody that was in that studio was international. There were people from Japan, people from Poland, from America, too. Obviously that is just adding layers and layers and multiple perspectives to a single project. That is super smart. I want to do the same. I'm doing the same actually. (Laughs)

Amy: Yes, that makes sense. This is where all the seeds were planted. While you're in school for architecture you're also kind of getting into product design as well, right?

Rodolfo: Sort of. Because I was very interested in seeing how the handles were made and how a handrail could end up in a curve or something.

Amy: So your attention to detail pulled you all the way through. Not just fit and fixture, but then color, surface treatment, and then the items that would be placed in there because that's what creates the environment, all of that together.

Rodolfo: Correct. In the end it's about the story. That it is narrated in multiple scales. I remember one day a teacher that was after I studied here in Milano I had to go back to Caracas because at that time they didn't have a double titulation program that you get your title in Caracas and then here in Italy you graduate as well as an architect. Back then I had to get back to the Caracas to present my thesis there. And a teacher when I was doing my thesis, it was a convention center, (laughs) I remember that clearly because I was super excited for the Milan Fair.

It was like Venezuela needs a convention center so I'm going to design it. During that process another teacher just saw one of my corrections and says, “Listen, you should do graphics, too, because the layout of these floor plans and how you're presenting your stuff, it's really cool.” Then it opens up a whole conversation that basically architecture, graphics, and then I translate that and scale that to product as well, it's the same because you are working with a structure, you're working with tension, you're working with geometry. It's just 2D, 3D, it's a matter of materiality. It's the same. It's the same.

Amy: It's the same and yet you said it's a variety of scales, right? So I almost think of it like if you're telling a story it's the punctuation, it's the inflection, it's the way your voice modulates, and it's the non-verbal communication as well as the verbal. It's all of that to communicate in a way that resonates. It can't be an outline; it can't just be the bullet points. It has to be the full personality.

Rodolfo: No, because that's soulless. (Laughter)

Amy: So how did you convention center turn out? You did well with that?

Rodolfo: Oh amazing. I won the best thesis of that year and I won an award, an internal award and everything. It was just spectacular.I knew the guys that were in the semesters below me, they saw me later on and said, “Dude, we sort of hate you because after your presentation we now need to do three times more work (laughter) because everybody is expecting these things.”

Amy: You raised the bar. Now we have to get better at what we do. (Laughter)

Rodolfo: They actually invited me to teach. So I was able to teach there, design for two semesters. It was amazing. It's an experience that I loved and I take very close to my heart.

Amy: I can tell. You already mentioned something about teachers and I saw that in your resumé and for some reason when I saw that it really clicked. I don't know why I didn't know this about you, but I sensed something from your personality that you would be a good teacher but that it would also be really meaningful to you to be able to help share what you've learned and to help cultivate it in other people.

Rodolfo: Yes. I have like law in my life that it's always like giving back. I had so much help from my teachers and from mentors and people even after I left the university. The universe puts a lot of mentors in front of me and this is people helping me. I feel that I have that work to just reciprocate that, not to my mentors but to other people, to help other people to see what they are not able to see and that is what I love about teaching because students don't know that they are so good. I just recently ended a period of time in Monterrey teaching. After 10 years it was an amazing experience and the last day I was saying goodbye to all the students and one of them said to me, “Oh you know we're very grateful because no one ever believed in us the way you believed.” Yes, you were basically pretty tough to deal with. This is the student telling it to me because I'm very strict. As I am loud with my laughter, I am as extreme in discipline.

Amy: I'm not surprised to hear that and I'm glad that teaching sort of filters into your life. You know, it sort of punctuates your life when it's time. It sounds like teaching was also your first step into the professional world. And then you founded your studio, the Rodolfo Agrella Design Studio in 2015 so we have a few years to cover as the early chapter of your career and I wonder if you can tell me about that.

Rodolfo: So the reason why I left the position of teaching in the faculty was because I was selected to participate at Salone Satellite. That was 2010. I was at the faculty and the dean reached out to me and said, “Listen, Rodolfo, Marva Griffin is coming to Caracas with the Campana brothers and they are doing a workshop here and they are asking me for 10 people and I want you to be one of them, to participate in that workshop.”

Okay, great. Amazing. Amazing. I knew who was Marva and I knew the Campana brothers. At that time I was not only teaching at the faculty, but I was also working. I worked with some architects and an event company; I was like the creative director for that event company. So we would have a sense of what the Campana brothers were doing back then. That workshop was sponsored by the Cisneros Foundation. It was really intense. Three days in Caracas with Humberto Fernando just designing stuff. Then the last day of the workshop everybody had a piece and Marva was just walking around and she saw one of my pieces. “Well you should apply for next year for SaloneSatellite. Do you know what SaloneSatellite is?” I was like, yes. I was super scared of her. Really scared of her. I was like, 'yes.' So I applied and I referred everything to go there and I presented.

The first time that I received it internationally was 2011 at SaloneSatellite and that is where I felt my career was launched formally in a very interesting way because I didn't have any money to go. I struggled a lot in order to produce stuff in Venezuela, do the prototyping and all of that. I was counting with the cultural branch of the government just to help me pay for some things and they said, “Yes, we will send everything to Milan,” and nothing arrived. They never sent it. I was in Milan at SaloneSatellite. Days go by, passed by and I was like 'where is my stuff, where is my stuff, where is my stuff.'

Amy: Are you just there in an empty booth?

Rodolfo: Yes. But listen to this. Because I knew that that was a special occasion I reached out to the best people that I could and I actually reached out to Fran Beaufrand who is an amazing photographer in Venezuela. He was the top art photographer in the country and I just reached out to him and said, “Listen, do you know who Marva Griffin is?” Yes. “Do you know what's Salone Satellite is?” Yes. “Okay, so I was selected and invited to go to the SaloneSatellite and I need really good pictures of my products because I need to show my products.”

I don't have any money to do this and I show him the project and he looked at me and says, “You know, I'm going to get pissed if somebody else shoots that. I really love the project. I really love your energy, let's do it.” And that happens with other persons, too. Valentina Semtei, she had a gastronomic lab and the first piece that I designed was a cookie because I wanted to do some food design stuff and she said exactly the same.

So I had very good pictures of my products. The day before the show opened I went to a printer house and just printed huge posters of my products and then put it there because I said, you know what, I traveled up all the way to here back to Milan not to sell a product, I am selling myself and my ideas and my approach to design. So I was there the whole fucking week teaching how my products, my things. Marva was pissed. And I was super scared of her because she's Marva Griffin. (Laughter) But then something magical happened the first day of the show. This German guy came. It was the first day, the first hour of the show, and he just stopped by because all the manufacturers, the first thing that they go to is the Salone Satellite. This guy looked at these servers that I designed and made in stainless steel and he was like, “Do you do that in plastic?” I was like, “No, I can do it in stainless steel because in Venezuela we don't have plastic.” “No, no, no, no. Don't worry. I'll do it.”

So that was Stefan Koziol from Koziol in Germany and he gave me his card. I wasn't aware of what Koziol was or who he was but the fun thing about the Salone is that the people that are next to you are either from Germany or from [** 0:41:19] in front of me and we became friends because of that. I was just like going to these German guys, “Do you know who is this Stefan Koziol, it says that's he's from Germany.” It's like, “Dude, this guy is like the top notch thing.”

Amy: Oh my gosh. The first hour. You don't even have any products; you just have photos.

Rodolfo: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. So by the end of that first week I was able to go and I'm always joking with Marva about that because after we became super close friends. At this point she's like my design godmother, I would say. (Laughter) She's one of these mentors that the universe had put me in front of and I love her. I remember that by the end of that week it was just like 'Marva, look I have good grades,' like a kid that goes to the mom and says, 'hey listen, I have good grades.' I have a contract. I signed a contract. (Laughter) Then that product was the first international product that I launched and the one that won the special mention at the German Design Awards. It's an amazing story that I always love to tell because especially in shows and things when I see people that are like 'oh no, I'm not going to do anything because I don't have the resources,' or it's very uphill for me, or people have I have a mirror and then the mirror breaks in the middle of installation. 'Oh my god, what am I going to do?' Nothing. Just be there and pitch your idea. You are here to pitch your idea and so people can know you.

Amy: I love your resourcefulness and I love through all of this you've had an openness which is no matter what curve balls I get thrown, I'm still here to do my thing so I'm going to do it. I just might have to wear a different outfit or change up my dance steps but I'm going to do it. (Laughter)

Rodolfo: Yes, absolutely. Absolutely. And that is part of being Venezuelan to be honest. Because Venezuelans are a highly resilient people and we have developed a magnificent approach to adapt to things, especially I am always saying that Brazilian soccer players, they are trained on the sand at the beach which is the worst conditions. And they are very good playing at the beach. When you put that guy in Europe with the proper shoes and the proper field, they are going to be fantastic. Basically I was trained in Venezuela where there's nothing so everything needs to be created or you need to solve things in a creative way with what you have. That generates an elasticity in the way you approach things and the way you design things. Then passing through all of these (laughs) experiences also allowed you to test that flexibility and adapt. It's an adapting game, I would say.

Amy: I like that you phrased it as a game because I do see you sort of treating it like a soccer practice or like you're gamifying it in some way. No, this is all just... how do I get better at this? As opposed to a more 'woe is me' kind of why do I get all these hardships? You know what I mean.

Rodolfo: No, because it should be fun (laughter) so make it fun. Flip the coin. (Laughter). We can pass through struggle laughing. (Laughter)

Amy: I love it and I'm taking notes. (Laughter) Everybody can I think take a little bit more of this into their life philosophy because we've been through a pandemic and we've all had to recognize our own weaknesses and resiliency and some of us also realized just how strong we are through that. But maybe some of us could also realize just how much more joyful that could have been (laughs) if we had a lighter-hearted attitude.

Rodolfo: I'm always saying that that period of time was a human time-out. Go to your room, think about what you did, and when you're ready you can go out. (Laughter)

Amy: I like that. I like that. That's a really good way to frame it. Okay, so get me to New York City because it looks to me like you moved to New York City around 2014, okay.

Rodolfo: Yes. This is the interesting thing, I wasn't planning to live in New York (laughs) and I wasn't planning to leave Caracas. Even if I'm very structured this was something that happened organically. I went to New York for the opening of a show that I had at the MAD museum at Columbus Circle about Latin American design. New Territories was the name. I went just for two weeks for the opening of the show. They were asking designers to do a lecture and so on. So I went there.

At that time I was in Venezuela and I had my studio in Venezuela working for different clients doing interiors and more related to hospitality environments and stuff like that, and designing products. It was super hard to get a ticket. Somehow I found a way to come to New York and I had to travel like 12 hours to get into New York. It was a horrendous experience because I felt that I was escaping Caracas. The trip was a mess. I arrived, I rented an apartment for those two weeks, and after 12 hours of traveling which is normally three. I arrived and I took a shower and went to bed. I meditate a lot and I was meditating and saying, “You know what? The universe just send me a signal that this is the proper thing because it doesn't feel like it was the proper thing.” Because I felt that I was escaping. The day after, the first thing that I do in the morning is just check my emails because I was traveling the whole day yesterday and I couldn't check anything.

I received an email from Koziol, the German company, saying, “Congratulations! You won the German Design Award with a special mention. From where do you want us to buy you the ticket so you can come to Germany and receive the award?” I was like 'from New York.' (Laughter) So after that I went to Frankfurt to receive the award. That was like three months. The time was three or four months. It was the opening of the show in New York was in November so I was able to spend Christmas with my family in Seattle, visit them, and then after that I will go to Germany.

Then during that time everything in Venezuela started to be on hold, projects, a lot of cancellations and stuff. Okay, well this is another signal that I have to read very clearly. I'm going to be in between Europe and Latin America so the best place is to stay in New York. So I moved to New York and at the start I have no contacts here besides the people that I knew from the show. What should I do? How do I open up a studio here being no one? Nobody? In New York. A friend of mine was working at that time at WeWork and he said they are looking for designers, architects, graphic people, product people. Okay, this makes sense in the overall scheme of things because I need to learn the codes, how people work in the US.

Amy: Building codes but also the social codes.

Rodolfo: Correct. In the future if I want to have a big studio here in New York I need to understand how things work first in order to tweak it and make it my own.

Amy: Was this during the blitz scaling period?

Rodolfo: Yes. It was just before what happened on that bomb. So I was in charge of the whole crisis, doing projects and a lot of projects in New York. I could tell how hard it is to connect architecture, design, graphics, and product from the American perspective.

Amy: Yeah, they are still pretty siloed out.

Rodolfo: Yes. I was like this is something. There is something here that needs to be something. (Laughs)

Amy: Do it. Do it, Rodolfo, we need you.

Rodolfo: So we are on it. (Laughter) Yeah, I discovered that there is no umbrella that can coordinate all of this and make it cohesive and create an experience through all of these things. And because I basically don't care about the difference between one thing and another thing or the limits between the disciplines, I don't care, I know people will just say, “Rodolfo, it's the Venezuelan-Italian stuff.” No, it's true. Compartments are not great and especially within the design world you need to be open to collaborate, to overlap stuff without ego because it's an ego thing. So I opened up, my studio, the Rodolfo Agrella Design Studio, and now we do all of that. (Laughs)

Amy: Yes, I know. Okay, you opened the studio in 2015 so you have been at it for eight plus years. Give me an overview of what the studio does. I know you do everything but maybe flesh it out in a little more detail. And then I would love for you to take one project, let's say, and illustrate your creative process through the whole thing

Rodolfo: We do product graphics, exhibition design, interior design, and architecture. We basically work with space and what you experience within that space. That's what we do in the Rodolfo Agrella Design Studio. We have a team, that is why I like to when I talk about the studio I talk in plural because we're a lot of people. Even if I am the face of the studio, we are a group and I have graphic designers, interior designers, people who work with animations and 3D, and sound-scapers because I love to include sound in what we do, and product designers. It's a very interesting mix of international people also, obviously. (Laughs)

Amy: Just to get business-y for a second, are these people you contract with that you have on heavy rotation? Or are these full-time employees that you are responsible for in terms of their workers' comp and benefits?

Rodolfo: I have a core team that is fixed and then depending on the pipelines and the specific kind of project that we do...we just up and up. It's always the same people basically because I believe that once you find somebody that is good you need to keep it, (laughs) and not just keep it, teach the person to do other stuff rather than what they are good at just for the sake of making them a little bit more flexible.

Amy: And also so they don't feel trapped and stagnant, because that's not good for anybody.

Rodolfo: Correct. Correct. Yes, I love to do that as their boss. (Laughs) It's so hard to identify a project, but I will say that doing an installation for Bernhardt Design last year, NeoCon was very interesting. Also doing other projects for Wanted with Claire and Odiel that is amazing. I mean the windows for Heller at the moment, design store, all of these projects have different nuances and it's because what we do is so diverse.

Amy: That must be so fun. Everything is new.

Rodolfo: That's it. You nailed it, girl. (Laughter) That's why I am always laughing and the people that work with me are always happy, because we're just having fun and basically we have fun because we don't do exactly the same all the time. That's why it's so hard to answer this question. One of the constants in all of these things is that I sort of 'date' the clients before getting involved.

Amy: Oh yes, tell me about the courtship.

Rodolfo: We need to like each other. We need to like each other a lot because that way you can build a net of trust and allow the client to speak freely, and then the client will allow us to do and to create freely. Now people knows this because I just say it, but that's not normally my presentation card, let's say. Like, “No, we need to date.” No, if we actually like each other then, even if I don't know you and energetically we just click, I know that this is going to be a success.

It happens to me with Jerry from Bernhardt. Bernhardt was known by its very severe, clean look, everything super white, no major colors. Then the first time that I had a conversation with Jerry about the installation I said, “You know what, Jerry? We should do color.” And he was like, “Okay, yeah. Let's do it.” Then later on when we did these huge light boxes of color tinting the whole space, it was amazing and everybody was like, “Dude, how did you convince Jerry Helling to do color here in Chicago?”

No, I didn't convince him, I just said it and that's it. The same thing happened with John Edelman. He reached out to me for Heller to do the windows at MOMA just because of that. Listen, I really like you (laughs) and I know you're good with color. What do you think to do the project? And it's like of course and we ended up doing something fun, visually fun.

Amy: So I a sort of curious because you are now known for being really good with color and I can imagine people that come to you for projects would trust that because you've built up a reputation. In the early, or let's say this project with Jerry Helling and Bernhardt, do you think the trust came from your relationship or from your portfolio?

Rodolfo: I thought of this also at some point. How should I present my stuff? You know what, the trust comes out of how convinced you are about your own ideas and that's it.

Amy: Correct me if I'm wrong, but I also think as an architect and somebody who has worked across design disciplines and has a track record for actually executing all the way through to the built detail, you also have a kind of confidence. 'I can do this innovative thing because I can figure out how to do it.' So therefore I'm going to present this idea with a very, very firm 'it can be done.' How are you going to do it? I don't know yet, but I will figure it out.

Rodolfo: Yes. Exactly. And we're going to make it within the budget. (Laughter)

Amy: Now that is music to their ears, I'm sure. That's what really gets you in from dating to marriage.

Rodolfo: Correct. That is something once again related to the flexibility and the way, this ability to adapt to changes and different variables. Because you can do it.

Amy: It's a resourcefulness, that's the polite word. But it's also a scrappiness.

Rodolfo: Yes. (Laughs)

Amy: One of the things I learned early on that I count as an ace up my sleeve is this really vast sense of material knowledge. So if I can't get what I expected in, I can figure out another material that I can get that will still translate the essence of the design. I might have to change the design a little bit but the essence is still there.

Rodolfo: Correct, because the idea is the same. The ways to communicate that idea are infinite, it's a matter of building a criteria. I remember very early in New York working people would just spend three hours deciding what hue of red they would do. That's not going to affect the narrative. You're just building walls on your own ideas. No, just make a decision and if it doesn't work this time, it will work next time. That's it. (Laughter) But move on and make it happen. Because otherwise you get ‘freezed’ there and things don't happen because you're overthinking everything. Oh my god, there is this fear to do.

Amy: I like that you said criteria because if you have a framework of criteria for a project or for even your design process, then you can always make decisions on the fly because you know what the criteria is. But if you're just given one tiny portion of a project and you're not part of the greater whole then of course you're trying to make your little portion sing. But it's like only being one paragraph in a play. I also just love that even on your website and in your approach you say openly that happiness and playfulness are design tools that you work with.

Rodolfo: Yes.

Amy: Clearly. And I like that those are both ways of being, not dogma. What happens then is that comes through in your design in a way that each individual gets to translate and resonates into their own sense of happiness and playfulness.

Rodolfo: Correct.

Amy: I want to ask you kind of I guess a personal question about that. Which is your joyfulness appears to come naturally and I'm sure it does, but joyfulness is also a choice and it's a practice and it's something that needs to be cultivated and maintained. It's like a two-part question. How did you learn that or who from? And when it's challenged how do you protect it or get back to it?

Rodolfo: Well this is such a smart question, Amy. Brava. (Laughter) Because you are tapping into what I consider is the essence of me. I learned to laugh a lot and to be joyful even on hard times thanks to my grandpas, both of them. They were just amazing, amazing guys that were just laughing all the time. Both of them struggled a lot in their childhood and even just to build a family.. When I realized that and when I knew and started to learn a little bit about their stories and comparing the real stories with what I actually knew about them, it's so crazy how these opposite things can create such a magnificent energy, I would say. I learned how to laugh through them and through my family. Using the laugh as a tool, it's something that I learned after.

Amy: You mentioned that early on. Talk to me about that.

Rodolfo: Yes, because people connect to happiness and to joyfulness. Even the Grinch. Everybody connects to that. And I feel like the universe gave me this laughter for a reason and I have to use it (laughs) for a reason and it comes naturally.

Amy: I can tell.

Rodolfo: Yes, I am obsessive and I structure things working-wise, but this thing is not. It comes naturally. I learned how to recharge that tool. I meditate a lot. I have a lot of 'me time' because I consider myself even, this is crazy and this is going to sound crazy, but I consider myself an introvert. (Laughter)

Amy: Yes, it sounds crazy. And yes, I understand.

Rodolfo: Yeah, because I like to be with myself. I can manage small groups beautifully. Big groups, if there are a lot of people from small groups that are there (laughter), that time of me thinking and meditating. I do doodles and drawings every day and I call it my morning meditations because it's like me getting back to that child that was playing on that little table because I just do it and I carry it with me all the time. I have it wherever I go, just a bunch of markers and a sketchbook just playing with color. I'm not solving any problems; I am not creating a project or nothing. It's just the hardest decision is what is the first color that I will grab. That is a way that I found to recharge that joyfulness, when people see you like this they want to have a piece of that.

Amy: And that's draining if you're not careful.

Rodolfo: It's draining if you're thinking that everybody wants a piece of that. (Laughter) it's there. It's the same thing when people say 'this person copied me.' What's the issue with that? You have more ideas where that came from, right? Something better will come from you. That's great. So in my case with the energy, I have more. (Laughs)

Amy: Are there times when you have gotten yourself burnt out or spent your energy too voluminously without replenishing?

Rodolfo: Yes. I learned how to protect that and to channel that the proper way. Because sometimes I will just be, you know when you are in the trade shows and in all of these design fairs and stuff, there is a lot of energy out. Then you're basically putting everything out and you are forgetting about yourself. Then when the fafir is off then you have a full week of recharging that happened to me a couple of times. Then I realized listen, I need to find tools. It's more than tools, it's an unconscious criteria. Same as in design. I don't need to be liked by everybody. It's a matter of being true to yourself, to be loyal to yourself. And I am loyal to that kid, that small kid that I tried to keep alive inside of me.

Amy: Good. Good, I'm glad to hear you have tools and you have practices, and that you are actively nurturing that small kid. Does the same apply to instances of trauma, tragedy, or grief? Do you have a perspective like 'this won't last forever, I just need to process it.'

Rodolfo: Yes, that story that I told you about the first time I exhibited at Salone, that was hard. That was super hard. I tend to process things like trauma and stuff not immediately because immediately I act. If I need to solve something I will solve it. Then I let it sink and therapy, it works. (Laughter) Find somebody to talk to. It sounds like my life has been a circus in the happy place. No. But I don't want to focus on that. Yes, that happened to me and it happens for a reason. When you are passing through that moment, that trauma or whatever, it's just a matter of you need to pass through it. The sooner you get out of the other side of the tunnel, it's the cliché moment, it's going to make sense. Everything will make sense later. That's why I act. I proactively react to things because that way I feel like the sooner this is over, the better.

Amy: I will tell you, if we're ever on a boat together and it's a ship wreck and we get stuck on a desert island, I will be so glad to have you on the team. (Laughs)

Rodolfo: Listen, I was in the Boy Scouts as a kid (laughs).

Amy: Oh my gosh, we would have the best hut ever.

Rodolfo: You might just have the side hut. (Laughter)

Amy: Okay, you beautiful human. Your life is in progress. So cast your vision to the future and tell me something that you want to cultivate or to draw into your life in order to fill out the picture.

Rodolfo: I don't want to fill out the picture because that frame is always going to get bigger. I would love to keep doing what I'm doing. On a larger scale, yes. I would love to impact larger audiences. And I would love to connect the past and the future. That is what I would love to do and we're working on it. I'm very interested in Venezuelan indigenous peoples' arts and crafts. I think there is a lot of industrial design knowledge there without knowing and I'm very interested in the metaverse and why it's that thing that everybody is scared about. How is that going to actually actively translate into the near future. Because if you look at things honestly, 20 years ago there were no Apple phones, iPhones. There were not. Now everybody has one, but 20 years ago it was a crazy idea. So we are at the moment of the century that somebody needs to do it, to grab that opportunity, and we are here to do that. That is something we're actively building, yes.

Amy: Can't wait to see how that unfolds. That was a nice tease for the future.I can't wait to see. I know you're in Milan now. I can't wait to hear the reports and I can't wait to see you in New York and to see the installations that you're doing for Wanted Design and ICFF.

Rodolfo: Also Heller. We're doing Heller Gallery. Next generation of modern. It's an installation that we're doing to launch new products. It's basically the first installation that Heller does during the Design Week so I am very happy to be able to design that.

Amy: Will it be at the show or is it in an off-site?

Rodolfo: No, it's outside. It's at Heller Gallery in 10th Avenue. We're doing something really cool. But then that happens in parallel to ICFF and Wanted Design and I am really, really, really happy to be working again with Claire and Odiel, I love them. Doing this art direction for Wanted Design and doing a few common spaces within the fair.

Amy: Yes, which will be the most vibrant places in the Javitz.

Rodolfo: It's going to be fun. (Laughs)

Amy: Rodolfo, you make my heart so happy. Thank you for sharing your joy, but also thank you for sharing your humanity and the depth of your soul and your practice with me.

Rodolfo: That's so sweet. It's a pleasure to talk to you obviously, and to be able to tell my story and guided through you which is really sweet. I'm really thankful.

Amy Devers: Hey, thanks so much for listening for a transcript of this episode, and more about Rodolfo, including images of his work, and a bonus Q&A - head to cleverpodcast.com. If you can think of 3 people who would inspired by Clever - please tell them! It really helps us be out when you share Clever with your friends. You can listen to Clever on any of the podcast apps - please do hit the Follow or subscribe button in your app of choice so our new episodes will turn up in your feed.We love to hear from you on LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter - you can find us @cleverpodcast and you can find me @amydevers. Please stay tuned for upcoming announcements and bonus content. You can subscribe to our newsletter at cleverpodcast.com to make sure you don’t miss anything. Clever is hosted AND produced by me, Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven.

Rodolfo Agrella, photo by Francisco Fernandez

What is your earliest memory?

The petrichor every morning in my childhood home, I remember it super clear, and every time I smell it around it takes me back there.

How do you feel about democratic design?

The pure core of design is democracy. Design exists to solve issues for humanity, for everyone without distinction. I cannot think of anything more logic.

Rodolfo circe 1990

Rodolfo drawing in 1988.

What’s the best advice that you’ve ever gotten?

“Go for the YES, you already have the NO”

Rodolfo at his sister’s 15th celebration with all his siblings

How do you record your ideas?

I tend to sketch them, but I also write words or save an image that triggers the idea, it’s like a protecting the idea itself using a code I only know…

The Avila mountain from Parque del Este

What’s your current favorite tool or material to work with?

The Sunlight! I find it highly poetic, and we need more of that!

Central University of Venezuela, Architecture School Building exterior and Rodolfo

last year sketchbooks only [2022]

The space at SaloneSatellite 2011

What book is on your nightstand?

Design as Art by Bruno Munari, I have two editions, one travels all the time with me.

Why is authenticity in design important?

We all came here with a specific purpose, by being authentic in whatever we do —including design— we honor our purpose.

Favorite restaurant in your city?

I have a few depending on the mood. Sant Ambroeus in Soho for something close to Italy, Aliada in Astoria for healthy mediterranean, Bemelmans for a real Manhattan and jazz.

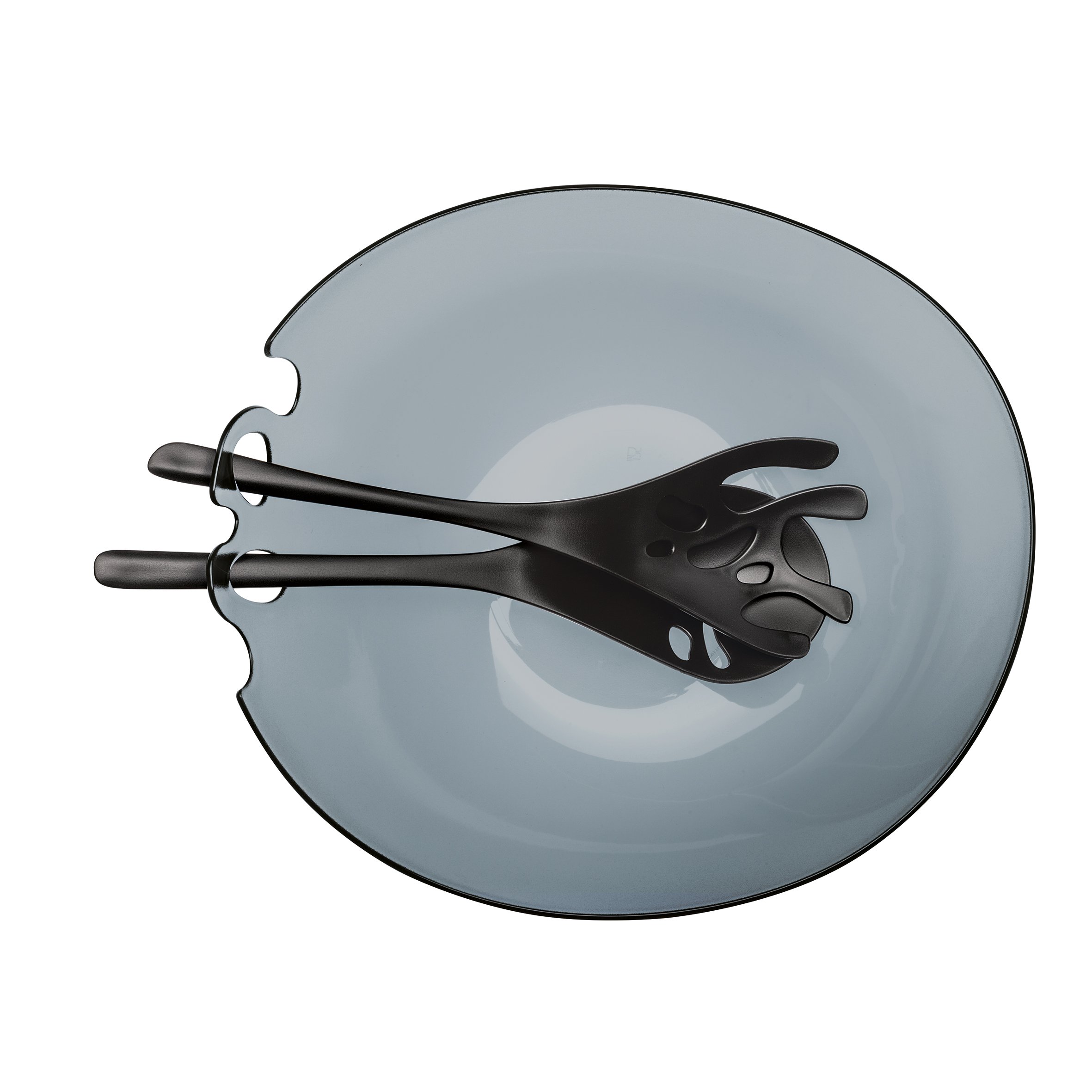

Shadow Set by Koziol

Teneo, cassava and cacao utensil. Image by Fran Beaufrand

What might we find on your desk right now?

A pile of samples waiting to be reviewed and approved. My morning meditation sketchbook, the projects sketchbook, the to-do list sketchbook and 2 glass cylinders with 0.5 Muji markers and felt point sharpies. Room temp water, and Venezuelan cacao nibs covered in chocolate.

Heller x MoMA window

Bernhardt x RADS, Chicago showroom. Image by Christopher Barrett

Who do you look up to and why?

Both my grandpas, their stories of resilience inspire me all the time. Professionally, Bruno Munari and his approach to design as a game.

What’s your favorite project that you’ve done and why?

Teneo, the cassava and cacao cracker I designed over a decade ago. It was such a simple yet complicated project, out of my comfort zone yet so deeply rooted to my culture.

What are the last five songs you listened to?

Our House from Madness

Knee 5 from Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach

Il Cammello e il dromedario from Il Piccolo Coro di Milano

Piano merengue by the Venezuelan Philharmonic (Orquesta Simón Bolivar)

Smalltown boy, Orville Peck cover version

Yes, I love a good shuffle!

Where can our listeners find you on the web and on social media?

rads.group and @rads.group for projects

@rodolfoagrella for curious…

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.