Ep. 188: Afrotectopia’s Ari Melenciano on Synthesizing, Art, Tech, Epigenetics, and more

Artist and technologist, Ari Melenciano, spent her youth obsessed with music, art, and gadgets. A year in Barcelona, a city that valued art as she did, left a meaningful impression on her. Back in the US, frustrated at the racial inadequacy of academia and technology, she founded Afrotectopia, a cultural institution building at the nexus of art, science, and technology through an Afrocentric lens.

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to artist, technologist and researcher Ari Melenciano. Ari's art and research practice explores computational anthropology, societal subconscious intellect, the ethnographical morphing of artistic expression across diasporas, speculative design, the formation and embodiment of mythology and rituals, and the materialization of omni-scoped research in the form of quasi-pseudosciences. Yes, that is a mouthful, and Yes she is absolutely as smart and fascinating as that sounds. She is the Founder of Afrotechtopia (in 2017) - a cultural institution that is imagining, researching, and building, at the nexus of new media art, design, science, and technology, through a Black and Afrocentric lens. Afrotectopia has hosted talks on things like creating an anti-racist technoculture, and created interactive projects like metamorphosis, an “audio-visual healing environment.” An academic and educator, she is currently teaching courses on emerging technologies like A.I., art, and design at New York University and Parsons, The New School. Her work has been supported and published by Sundance, The New York Times, The Studio Museum of Harlem, New Museum, MIT Media Lab's Space Exploration Initiative, The National Endowment for the Arts, Deem Journal, and so many more…I’m pretty confident that listening to her will change the way you see everything… here’s Ari….

Ari Melenciano: I am Ari Melenciano, I work and live in Brooklyn, New York City and I create because I love to learn about the world.

Amy: I learned so much in researching you and your work that I am just so excited to dive in. But before we get to what you’re doing now, I want to learn about young Ari. Can you take me back to your formative years and tell me about your childhood, your family dynamic and the types of things that captured your young imagination?

Ari: Yes, I was born in Miami, Florida to two parents, they came from the Dominican Republic, so both of them were immigrants. And then I mostly grew up with my mom and my sister and we moved from Miami to different parts of New York State. We lived in Lower East Side, New York, for a little bit, and one of my favorite stories that my mom tells me, when I was younger, I was like four years old when my older sister was in dance class. My mom and I would stand on the corner and I would just pass out all of my drawings to strangers just because I loved my art and I wanted everyone to have it too. So I reflect on that a lot, what does that mean as far as who I am and just loving to create. Very much invested in the arts. Grew up loving art. My mom also invested in my sister and I going to different museums, different art supplies. Also was a self-proclaimed gadget girl. Loved, loved calculators, for whatever reason, anything with buttons. Everywhere I went, before even going to school, I had a backpack full of gadgets. I think also my love of art and also my love of the idea of technology and for whatever reason I had this inclination that them two coming together would be something really beautiful, even though I didn’t really get to see that too much around me. I just thought that that… something about art and tech was really special. So I think whatever I could get my hands on, that was somewhere to both of those.

Amy: Were you an outlier with your mom and sister or were they interested in these… I mean your mom was clearly involved in taking you to the museums and things, so art was celebrated in the family. But did this gadget girl personal persist throughout the family or were you the owner of that?

Ari: My mom, she’s always telling me about another cooking gadget that she’s bought (laughs), so maybe that, maybe we just like stuff, that’s technically technical, I don’t know. But no, no one around me was interested in that at all.

Amy: Your sister is, you’re older or younger than your sister?

Ari: She’s older than me by eight years. But we were just generationally very apart. But what I did get a lot from her was music, that’s how I became a big Aaliyah fan and knew all about the 200s, hip-hop, all that stuff.

Amy: Oh yeah, older sisters are great for that! (Laughter)

Ari: Yeah.

Amy: So now I want to hear about teenager Ari because that’s a time when many of us are lurching clumsily toward adulthood and struggling to individuate, but also trying to find our collective. I’m wondering what your teenage years felt like and sounded like?

Ari: Well even as a kid into teenage years, my nickname in I think pre-K was Silent Stream. So quietness was always a thing of mine. I was extremely shy and quiet for most of my life. And I think more like high school, that’s when I really started to branch out and [0.05.00] get more comfortable with myself. And then I kind of reverted again to being quiet in college and then probably in mid-20s-ish to now is where I’m back into, oh okay, I see who I am and I have a greater comfort. So teenager was very much, extremely introverted but also just extremely interested in the world. Academics was everything, I loved school. I loved school until high school and then I started liking the social stuff and not really caring as much as the academic stuff. Actually taking steps back, even in elementary school I loved school so much that some of my favorite things would just be coming up with different mathematical equations and then my teacher announced them out to the class and I would teach everyone this different way of learning the mathematical equation.

For me that was really exciting, of just taking a lot of time studying the way that we’re learning and thinking about new ways to do it. So school was really, really important to me. And then teenage years, the art persisted. I was always creating. I always was the president of my school in elementary school, middle school and even high school and I always left like a mural inside the school. So finding ways to bring art, use that to represent the community was really important. Always was very active, I played sports growing up, I was always on sports teams, every season in high school I was on a different… tennis, soccer, track, so just very active and creative and social, especially high school.

Amy: I’m kind of interested in this leadership position that you always had and went after as a shy person, that surprises me.

Ari: Yeah, it’s weird. (Laughter)

Amy: Clearly your drive to lead was stronger than your need to sort of recede?

Ari: Yeah, I think as I get older, I was just always afraid of saying the wrong thing, being the wrong thing. It was just like this fear, fear that was very much rooted in perfectionism. But I also really trusted myself and had a lot of confidence in myself. It was both like being really quiet, but also just, I see things that I don’t think other people are seeing. And I’ve always had this level of responsibility, like my mom tells me, you cannot carry the world on your shoulders. Because everything will affect me. But I just really want this place to be better. I see how I can make it better. So that was more of, I want to be a leader because I want to make it better.

Amy: Yeah, well it’s all adding up, (laughs) it’s all adding up. In terms of the college years, you went to the University of Maryland for your undergrad, then you studied in Barcelona for a bit before going to NYUs ITP, Interactive Telecommunications Program for grad school. Can you describe your personal and creative evolution during the college years?

Ari: Yeah, I went to university in Maryland and I really didn’t want to go there. I really wanted to go to an art school, but I just didn’t know how to apply to colleges. I did go to Maryland. Maryland is still an amazing school and I was paying in state for a really great education, so that was nice. But I think for me, I also just really wanted to use college as a time to branch out. I would go to school, then I would see my soccer coach from when I was five to 18, walking on campus. I’m like okay, this is way too close to home. I love to see you, but I got to get out into the world. And so I ended up studying abroad for a year in Barcelona because I really just wanted to get very far and figure out who I am and that sort of stuff. So Barcelona was so impactful to me, as an artist and like being able to live in a city that valued art in the way that I did. I just didn’t see that around. So immensely impactful. And then it also, in being in Barcelona, there’s La Merce Festival, which happens at the end of the summer.

So in that festival, the Moment Factory had projection mapped on top of La Sagrada Familia and this amazing, like bringing to life of this old church through technology. That was so much of what I had wanted to do as a kid, I just had never seen something like that. So that was so impactful and I would see that when I would travel all around, when I was in Europe for that whole year. Like going to Portugal, there were a lot of different opening ceremonies where they did a lot of projection mapping onto buildings, so that was very exciting. And after I left there I knew that’s the kind of work that I wanted to study, to do a profession like that. So I went to grad school and did creative technology ITP.

Amy: Ah, so it was impactful in so many ways. Did it satisfy a little bit of that craving to experience the rest of the world? Or did it just open a can of worms too?

Ari: It did both. I traveled before; I didn’t travel much as a kid. I had gone to the Dominican Republic one time and went to Spain in high school for some program. But that was the first time where I was like, oh wow, the world is huge and I’m so small. That was really exciting, to be in the midst of so many cultures. I was in college, drinking in the US, that doesn’t start until 21. I could drink at 18, be at a restaurant, have pizza and wine. (Laughter) So that was really exciting. But just being around different people, I think that was... it just opened me up in so many ways and I was there on my own, I didn’t know anyone. So I’m already a very independent person, but that really made me even more independent. Yeah, that moment was everything to me and it also just, it showed me that there are people out in the world that really… because growing up in the US, it can be artistic in different areas, but there are actually cultures that are immersed in the arts, even if they don’t actually even realize it, they just live in such an artful way.

Amy: Yes, that was really a big realization for me at one point too and I love that you’re doing your part to re-artify the United States (laughs) or from wherever your work is emanating from. Speaking of your work, I’d love to talk about your career trajectory. I know you’re an artist, creative technologist, a researcher, educator, academic speaker and so much more than that. You hack synthesizers, DJ, I mean it’s amazing the breadth of your interests and skills and the way that you sort of put them together to create work. But I’m deeply interested in Afrotectopia and you founded that in 2017 and I sort of did the math, was that during grad school or right after?

Ari: Yeah, during my second year of grad school founded that. And that really came from a variety of different experiences, one being finally in a program and it just felt like a dream come true where all the things that I loved were happening at one time simultaneously. Like to be able to learn technology in a way where I had been so intimidated before, like I had gone to a science and tech magnet program high school, really didn’t touch the tech, I would let the guy in my group kind of lead it. Just because I didn’t feel confidence in myself and I didn’t feel like I knew what I was doing and it stopped me from even trying. So to go to a tech program where I had this natural infinity towards art and tech, but didn’t have the comfort of computer science to approach it, to be in a program that taught it in a way where I could bring my artistic skills, like that was a superpower that I had. I didn’t have to rely on knowing all these different coding languages. So that gave me a huge confidence boost. And then to go and create and I’m learning all of these things about physical computation and creative coding, but I have all this art way that I want to apply to it. That was everything. It was a dream come true. And then the other side to it of just being in a program where all my professors are white, or at least not black. And then always being that student in the class where I was raising my hand saying, “This doesn’t seem like it’s very culturally sound,” or, “It’s not going to resonate across society.” I felt like I confidently had to advocate because it just didn’t exist there and that was a frustration. So it was a great time, but it was also extremely frustrating. It just very organically came to me, oh, let me just create a community, because I don’t know of a community that exists where it’s black people that are thinking about art and tech and we have all this access to all these different resources. And I want to make sure that black people can see themselves in this space because I didn’t really see myself in the space, for whatever reason, I had that inclination, but I didn’t see anyone that was doing any of the stuff that I’m even doing today that looked like me. So it was trying to figure out how can I bridge a community together where we can build each other up and show each other all these different tools and resources. And then also show the world that this community exists and that we should be tapped into and invested in.

Because I saw that clearly. It just didn’t feel like there was much effort in making sure that these kinds of people exist in these different programs. Because what was happening in my own program was happening across academia. And generally academia is very racially inadequate. Generally technology is extremely racially inadequate. I think just for me it was how can I show that this is something that is really valuable, to ourselves and to others?

Amy: You’re doing a phenomenal job of that, I think. For our listeners, can you give us an overview of what Afrotectopia is, the framework of it and I know it’s evolving over the years, so maybe you can tell us the story [0.15.00] of Afrotectopia as it evolves and intertwines with all of the other professional work you’re doing in terms of… I know you’re a creative technologist at Google for a couple of years and you’re on faculty at NYU and you were a MIT research affiliate. So all of that seems like it’s winding around together and creating a very relational field that’s super fertile.

Ari: So it was in my second year at grad school, and having all those different experiences, and so decided okay, I really want to create this festival that creates this community and brings all these different people together. So I told my program about it and got immediate support. One professor of mine, Nancy Heckinger just met me with all the time to help me kind of build up these ideas and she would have to slow me down because I wanted to create a week-long festival and she was like, let’s just do a few days. She was my brakes and also the chair of my program, immediately introduced me to whoever he could, just to get some support in that way. So it started off as a festival. We had it for a weekend. It sold out very quickly after being announced and really didn’t take much marketing, just putting a few things up on Instagram. And I think it was just something that people already really wanted and so people found their way to it and it just spread like wildfire. And it’s been kind of like an organic sort of success in that way of just, it’s reached people that it needed to reach and those people have really wanted something like that to exist and so we all just built it up. And so it started as a festival and that was during my second year, while I was also building out my thesis project. And then after wrapping my second year up, I had Afrotectopia and I was trying to figure out what to do with it. When I graduated NYU, they asked me to stay for an additional year to be a researcher and so there I did a lot of research on societal implications of big tech. And so while I’m doing that I’m also still thinking about Afrotectopia and what kind of programming can I do to make sure that we’re having all this fun with tech, but we’re also studying the ways that this can be really harmful and getting ahead of it and not letting these corporations dictate how we live our lives without any intervention on our part.

So that was when we started to do a lot of, like I would do programming at Eyebeam, which is a big art and tech institution in New York and do things like have an anti-racist techno-culture manifesto building. So people in Afrotectopia community, we could do that sort of work. And so it was a lot of just like, I already had a lot of connections within other institutions in the city and it was how can I bring Afrotectopia into that. And that’s generally been how Afrotectopia has existed, as a student at NYU and how can I bring Afrotectopia into the community there. Through my research affiliate with MIT, that was also of a similar nature of I was asked to do research at the Space Exploration Initiative, based off of the own work that I had already done. And so for me it was okay, I already have this community, that could be really exciting if we could kind of bridge these two and do work in that way. But I think also the way that I approached Afrotectopia has changed over time of when I first created it, it was very much, I see a lot of problems going on and I want to fix it. I want to diversify big tech; I want to show people that we exist. Of course I want black people to see that we exist too, but it was really, it came from a very oppositional kind of energy, like I’m really frustrated and upset with the world and I want to change that.

And how it changed was more of, you know what, this is the way that the world is. And that makes me reflect back to when I mentioned it, like always wanting to be the president, I think for me it’s also just like understanding, this is the way that the world is and it’s not always about fighting to make it what you think is better. Sometimes you just have to accept the world as it is and just do your part in your own little area. And so for me that changed the way that I looked at Afrotectopia. I don’t want this to be a tool where I’m constantly being an activist in the traditional sense of fighting the world. I want this to be a place where we can be beautiful together because we see how beautiful we are. we don’t have to convince other people of the beauty. We can just exist in it together and so it became much more, let me look inward. Let me make sure that when I design this festival, it’s not about us replicating the way that conferences are traditionally held, we have a bunch of panelists and everyone is looking to those people on the stage, or you’re not looking at yourself and all the things that you already know. So for the second one it was very much, for one, let’s understand who we are and let’s really revel in that. Let’s also empower everyone that’s on their own. Instead of having a bunch of panels, we had community conversations. People could gather and they could all contribute their insight because it was just elevating how we all know something, so let’s empower each other. And let’s design this future [0.20.00] not based off of what’s going on in the present, and what other people are doing, but the future that we want to build. So it’s much more proactive as opposed to reactive. Afrotectopia has kind of existed in three different phases. It entered the third phase of let’s not even just design the future based off of what we know, but now when this third phase with MIT, and doing all the space exploration work, but through a cultural lens of Afrotectopia, let’s actually exit this world, and let’s design a whole other world that doesn’t even exist. And so that’s what we’ve been doing for the past couple of years. And it’s also been really small. It’s been four artists, myself included and three other artists and we are collectively as Afrotectopia, as like a new design of Afrotectopia, thinking about what is space like, but through this cultural lens. And just working with each other and turning all of that, that work that we’ve done, the art renderings and the research into this book that we’re actually going to publish this year. So Afrotectopia has changed, even philosophically, of being this space that is challenging the norm to eventually just… let’s just look at ourselves and really champion ourselves. To then even let’s exit outside of this world to also being a place that has existed with a lot of people and then increasingly gotten smaller and smaller, which is very non-traditional to the way that people that I’ve seen really want to see Afrotectopia kind of exist in the world and other spaces like that. I think we’ve really incentivized and just like the capitalist nature of our society is, we’ve really incentivized scaling and growth in a numerical way. I’m just generally a much more intime person, especially being very introverted. I value so much more the ability to be intimate and to really build trusting relationships. And so as opposed to kind of getting bigger and bigger as it easily could have, it’s been much more, how can I just make sure that this is something that’s a space filled with a lot of trust and working with people where we really all just enjoy being around each other. And so it’s grown from there. But also with Afrotectopia, it’s something that I’ve built alone, as a sole founder and it’s something I managed alone as a sole producer. And I think that takes a lot of wear and tear. So I’m thinking even just personally, how to navigate that. Of being a human being, but also when I’m involved in Afrotectopia, I’m now an institution, I’m no longer just this human. And people see me as an institution. Having started off as a student where you don’t really mind doing free work, but now you’re an adult and you have to sustain yourself. And I see these kinds of problems happen a lot with people that just really want to do things for the world and they start off when they’re really young but then they have to figure out as an adult, how do you turn all of that into something that’s really healthy for you. So now it’s a space of figuring that out.

Amy: You sort of go from traditional conferences down to a more collaborative self-reflective kind of grouping, collective, your outputs are still open source and available to all. So it’s not like you’re keeping it for yourselves necessarily. But you are guarding the space in which it’s created so that it can’t be compromised by just being diluted or depleted or people not feeling safe or totally comfortable or not seeing themselves in it. And so just in general in the way that I learned that you have approached this… there’s a caretaking to it that’s really, really, really powerful. And a concentration of energy and intimacy that seems to me to be, when you concentrate something and at its epicenter it has all this potential. If that potential is shared in a way that doesn’t deplete the concentration at the epicenter, then it does seem sustainable. And so much of that seems like it is a process of caretaking and making sure that you keep that nucleus kind of nurtured.

Ari: Yeah, exactly. It’s like you really have to protect it. It’s a lot of emotional work and it’s also when you’re building for a community, it’s about race, like that’s so… and it’s the black race, there’s so much that’s in there and so for me, I’ve always been very cognizant of there’s just a lot that’s going to exist inside of a space [0.25.00] when it’s a face at the core of it, it’s very much about race and about blackness and just all that comes within that. I think also just as you were saying, you have to preserve yourself because when you’re approaching something that fragile, so much care goes into it. Every little thing matters. For when I have to protect myself as a human being and my energy, because all of that is going to enter the space. But I also have to protect any sort of energy that’s happening inside that space because as you mentioned, it also very much… like the biggest thing is that it’s helping way more people than have access to it. It’s always been very hyper local to New York, just because that’s where I am and then when the pandemic happened, that actually was a great moment for Afrotectopia because it allowed me to see oh, I can actually do things online and now it’s reaching people that have been emailing me to have things in their cities, but it’s way too hard to get to. So with our fellowship, during the pandemic, we had people that were in different parts of Europe, different parts of Africa, all over the world that were all coming together and thinking. So I think that was really special, but yeah, it’s very much about how can you protect that core and that energy when it’s so sensitive.

Amy: Creativity and the race thing makes it a doubly sensitive space. I can see the need for protection and I can see you doing it with a lot of care and thoughtfulness. And I’m wondering how you balance your own sort of career trajectory outside of that? You’re taking research affiliates, you’re teaching at NYU, you’re doing stints at Google, so while they seem to complement each other, I’m wondering if they do actually complement each other within you and within your own thought process?

Ari: Ideally they would complement each other. (Laughter) Theoretically they would. In real life, they do not. They take energy from each other. The research affiliates, that was great, like with MIT that was amazing because now there’s this intellectual space that I get to use as a foundation to empower the community of Afrotectopia. So that works really seamlessly. And then also my relationship with ITP, that’s great because I have such a great support system at NYU ITP and so whenever I want to bring in Afrotectopia related things, I can do it. Like I even create a course called Afrotectopian Ecologies and I had that for two semesters where students could come and we could learn all about these different philosophies and ways of engaging with technology critically.

Amy: Hot damn!

Ari: With Google, I worked there full time for two years and that was my first time working in a corporation and ideally that could have been a space where I could have built all the things going on around me. But that actually became a time for me to retreat because right before Google I had just been doing so much working. I was running Afrotectopia, I was doing my own residencies, I had my own freelance work, I was teaching five different classes. I was also an architecture student, taking four classes… I was doing an insane amount of work and it was just overworked to the point where I just became depleted. And then also I was finding moments where even trying to be very careful with things like Afrotectopia, there were tensions. Just because you have people that are all coming together that share a certain ethnicity or race, does not mean that everyone has the same values and ideologies. So I think that was a really big moment for me of okay, I have to be even more careful about how I approach all of these things. It was an amazing lesson for me. So with my time at Google, that was more of me for one just being really exhausted, but then also it’s such a demanding job that I didn’t even have time to do anything outside of that.

So I tried to do as much as I could with Afrotectopia, kind of building it and all my other stuff, but also I just had to be as healthy as I could for myself. So now I’m out, I’m no longer working there. I had to just like really take a step back and understand, I have to be really intentional and careful about the way that I use my energy and the spaces that I exist within because if it doesn’t align, then it’s really going to affect me in ways that I’m so good at covering up with work and being busy, but I can feel it and I can see how my body is feeling so… now that I’ve taken a step back and I’m a month away from that moment, now I’m just thinking really critically of what is it exactly that I want to do? Where do I want to put that.

Amy: Yeah, where do you want to put that energy. Well, I want to unpack that a little bit, but before we do that, I really want to get kind of deep into your creative process because it is fascinating and I want our listeners to hear all about it. You can pick a few projects if you want, to sort of [0.30.00] deconstruct your process as you’re giving us a description of the project. But what I would love to hear about is Metamorphosis because just the… oh, it’s just very exciting. (Laughs)

Ari: So Metamorphosis is this web VR experience where you can go to the website, metamorphosis.fm is the URL and you enter and it’s a space that I’ve designed that uses a few different healing modalities to just be this meditative space. And so the idea for that came from… I was in my apartment in Brooklyn and it was 2020 and it was just like a constant stream of protesting chants outside my window because it was in the midst of the pandemic, but it was also the second uprising of the Black Lives Matter movement. So there was just a lot of frustration and angst in that moment and I was thinking of things like my previous studies in epigenetics for one, of just understanding how these traumatic moments really embed themselves in our DNA and they stay there, generationally. So I’m thinking about that moment. I’m thinking about the power of being in the midst of protests and chanting along other people and feeling empowered by that, but also the things that we’re saying. Are we being critical about the things that we’re saying when we’re chanting? Like as good as it can feel to in sync, be with other people, chanting the same thing, also being mindful of what it is that we’re saying because we’re encoding that in ourselves.

So things like, ‘I can’t breathe,’ and ‘No justice, no peace,’ like these are the energy around those things, it’s a lot for someone to continuously say. So I was thinking about, is there a way where we can kind of reverse the impacts of epigenetics is it even possible for it to not be only about pain impacting our DNA, but pleasure impacting our DNA. If we meditate enough, can that reverse something? So I wanted to create a space where it was built off of the capacity of epigenetics, but also my studies in psychogeography, of loving this area of studies where it really focuses on how psychologically your environment impacts you. Your environment impacts you psychologically and how things like if you enter a church or an older bank or a place of a lot of importance, the ceilings are much higher because that is meant to signify to you that you’re in the midst of something great and you have a smaller presence. You know, to respect it. I love that way of thinking about energy, of when you enter a space you know that it’s significant. So I wanted to create that inside of Metamorphosis where I had higher ceilings, also setting how psychogeography talks about how when you have curved angles or curved walls and edges, that actually allows for more calmness as opposed to angular and rigid structures, so everything is very circular.

And then also sonically, how different Eastern cultures understand the relationship between different frequencies and different energy centers, like your chakras. Being someone that has studied sound design for a while, I wanted to create soundscapes that merged both the Eastern philosophies of sound, but also the percussion… the utilization of percussion in different Pan-African movements, like with the Haitian evolution and the use of the djembe drum and that being a communication method. So blended djembe drums and other African percussive tools, with Eastern philosophies on sound design and chakras and created a soundscape for each of your different chakras as you move through in this space, it’s just like very awe, hopefully, inspiring.

Amy: I love the energy and the intentionality at the base of it, which is if epigenetics and code traumas on our DNA, what can we do to either heal those traumas or to counterbalance them with a positive encoding. And I can see you thinking both as a healer and a technologist and of course an artist in all of this. And it strikes me as incredibly powerful to also be able to hear oneself reflected in the percussive rhythms that are being deployed. I think so many spaces just have this Western origin, or veneer even and so to be able to be in a space that isn’t so Westernized, even if it’s in your own mind. (Laughs)

Ari: Yes.

Amy: Is really, really beautiful and it would seem to be also a kind of quiet and self-reflective and nurturing way to kind of decolonize.

Ari: Yeah. I don’t really have any interaction with people that use it. It’s just a website. When I present it, people are excited about it, but I’m presenting it along with a bunch of other work. So I don’t really know what people’s actual experience with Metamorphosis is consistently. But from the people that I talk to one-on-one, back when I first made it, excited about it. I just shared it on my Instagram. I kind of just like make things, share it and I move on. So I don’t even know (laughter).

Amy: That’s probably healthy to not get too attached. Is there anything else from your electromedia practice that you want to talk about? I also definitely would like for you to kind of give us the overview of the 2020 Imagineer Fellowship.

Ari: Yes so things with my electromedia practice, I’m so invested in sound and just using sound in different ways. Some other things that I’ve been doing are… every summer, spring-ish/summer, I grow a garden on my roof and grow my own food and I just love plants. And so one thing that I’ve done more recently is starting to attach it to the front sensors, to my plants, to get the electromagnetic energy from the plants and then put that into my modular synthesizer and then turn that into these soundscapes. It’s like what if I could hear my plants, which I know they emit something, I don’t have the senses right now, I’m not aware of them to be able to interact with it in that way, but to turn its energy into sound is really exciting. So a lot of explorations with sound. With the 2020 Imagineer Fellowship, that was just one of my favorite moments within Afrotectopia because we’ve had two festivals and those have been extremely fulfilling, just seeing the way that people feel in those spaces and the times that we’re having together. But the Fellowship, I think that is what really inspired me to continue going in this more intimate way. Because the Fellowship actually only, what I had budgeted for, only plants, I budgeted for five different fellows and I met with over 200 people around the world who were interested in doing it.

And I was like, oh my god, there’s so many amazing… so I extended it to 10, so there were 10 of us Fellows that were together for a month and a half and what we did was, I came up with these different… before even announcing the Fellowship, I came up with these different areas that we could potentially explore as Fellows and decided the Fellows that were selected would be the ones to really decide what work we actually do. And they all wanted to do those that had already been predetermined, so it was great. We just jumped right in to all these different issues. Some of the issues, it was in the time of the pandemic, so it was how can we create a pedagogy that is culturally sensitive, but also online and technologically relevant, those kinds of things. A bunch of at the time urgent ideas and areas to explore. So what we did, the fellowship, the whole purpose of that was using the savings of Afrotectopia because again, as a sole founder, I don’t have time to fundraise. If I just have some money I’m just going to figure out how can I use this creatively to make something with Afrotectopia? So with the savings it was funding the Fellows to just dream. All we did was just dream and imagine for a month and a half. I would write everything down. I would create mirror boards for them to write their own notes down and then we also had, while I was interviewing for Fellows, so many people were interested in this and I saw that the biggest thing that they were interested in was just having a community of people that they could talk to about these kinds of things. Maybe they were in the middle of places where no one looks like them or they just aren’t in school anymore, so they don’t have a place to talk with people that are interested these kinds of things. In addition to extending the Fellows to being more than five to now being 10, I also, every week held a public convening for any of the people that had applied and for anyone in general that was interested. Generally was Black only, to come into this Zoom room and we could discuss the ideas, the same ideas that the Fellows were doing, but in a public way and we would also jot their notes down too. They would all put their notes down into a mirror board and the Fellows would use everything from the public convening as a foundational understanding of this is where society is right now. They’re thinking about these issues. And then we would also spend that weekend studying, going through our thesis, researching and we would turn that into public frameworks. Because as you’ve mentioned and identified, everything about Afrotectopia is open source. [0.40.00] How can we collectively in a small group, ideate and imagine and dream and then turn all of that over to the public and what might you all do with it. So I would just turn everything that they had, all these people had thought and make it into visual graphics to put onto Instagram and Twitter and then professors and all sorts of people would reach out and say, “Oh wow, this is great, now I can use this in my classroom.” And so it’s just like this constant relationship between the public and Afrotectopia.

Amy: I read some of the essays that were the outputs of some of the Fellows and they transported me. I mean it was really powerful and exciting and I felt some of the energy coming through them. I heard you say this, or maybe I read it, but there’s something really powerful about not just the capitalistic practice of paying for someone’s immediate value, but investing in them to imagine because the assumption is that that is valuable. And to share that imagination is exponentially valuable and I just kind of see that whole thing as a mushroom cloud of imagination (laughs) which is amazing. And it takes a very cognizant, intentional person to build a space like that knowing that it’s not about a concrete output and I’m not directing it from the beginning about where we’re going. I’m just creating the space to go somewhere.

Ari: Yeah that’s one of the big things that I learned with Afrotectopia. I can do all the planning and have this vision, but at the end of the day it’s not about my vision, it’s about the space that’s created, that’s the vision, but it’s the people that come in and they turn it into something that I couldn’t have even imagined. So that’s what I constantly try and create, is I called it the ‘container,’ it’s just that space. A lot of thought as you recognize, goes into how are we going to experience each other, but the best part of it is just the energy that people bring into it and what they want to turn it into.

Amy: You mentioned earlier something about being really intention about how you spend your energy. I’m really curious about this because I think it’s something that a lot of us are reckoning with and I think it’s something that we are kind of all understanding that capitalism and hyper productivity has the promise to beat that out of us and deplete us. But there are so many existing frameworks in place that demand your time, attention, your energy that you have to be very proactive about how you spend it and it sounds like you are and you’re really developing your own framework and decision making for how and where to spend your energy. And I wonder if you could share any of that with us? Where are you at with it now?

Ari: I am very much figuring it out and I have to fight myself all the time because I’m constantly coming up with business ideas or positions I want to do and it’s like okay Ari, just because you know that you can do that, doesn’t mean that you should do that. So I’m just floating right now. And I never thought that I would do that, leave a fulltime job, with no plans whatsoever and really because I had hustled for so long, now I’m like, I’m okay to just kind of give myself that breathing room to just figure myself out. No one is relying on me, no one is depending on me, so this is a moment where I think also me just understanding life is so much more than what we’re taught to believe. And it’s not all about clocking in every day. It’s not all about capitalizing… I used to be the kind of person where every moment had to make money for me. I was doing 20 jobs at one time. Any time I had a free moment, it was all about okay, how can I make money here? And I think that can be really addictive because it’s like you’re building your savings and you’re doing all these great things, but then you’re not really paying attention to who you are and towards the end of last year, what I was recognizing was I already had this idea that I wanted to go into 2023 way more about my body, way more about the human and less about the machine. And as someone that was working in big tech, I was spending 14 hours a day staring at my screen and I wouldn’t eat all day because I was just so busy. I wasn’t taking care of myself and so for me it became, okay, the number one thing is cooking for myself, really simple things, cooking, walking, tapping into all my senses, all those sorts of things. But then it’s also, okay, I’ve proved myself to a lot of different people, there’s nothing to prove. It’s more just understanding myself and I really want to devote a lot more time to understanding, okay, now you know if you work really hard and you put stuff out in the world, something can come of it. So what do you really want to do? What makes you really excited? Not what you’re good at, but what really makes you fulfilled, makes you excited to wake up and when I wasn’t doing that sort of work, but I was finding success, I was like, okay, this is the moment where I have to take that leap. I mean life is all about… what I told my friend the other day was, really life, what I’ve understood it to be is, you’re just that bird that’s on a cliff and you either decide to stand on that cliff because that’s where it’s safe. You jump and you fall and it’s a failure. Or you jump and you realize that you can fly. And for me, I don’t want to keep standing on the cliff and doing all the safe stuff and that’s what I did for a really long time, of just hustling, but also doing a lot of safe stuff that I was really comfortable with. Because I knew that there was just constant yearning to do something else. And so I don’t even know what that looks like, even today, but I just know that I had to just give myself some time to listen to myself.

Amy: So that’s what you’re doing right now, is listening to yourself? And tuning into your own regenerative cycles? Is it time to start planting on your roof yet? Not yet…

Ari: Almost, yeah. I hope so, I’m not the best gardener, in a few weeks I probably will start going and getting.

Amy: Do you believe or are you open to believing that a concentrated amount of well spent energy is ultimately more powerful than a volume of, a higher volume of diluted output?

Ari: That’s what I’m figuring out. That’s one of the number one things I’m trying to figure out. As I’ve grown up, I’ve definitely very much been someone that has their hands on a lot of different stuff and people… even in middle school, I remember I was trying out for the basketball team and the coach was like, “Ari, you just came from theater, you just were in a play and now you’re trying to… you have to pick one thing.” And that’s always what people would tell me, “Ari, pick one thing.” And I would be really frustrated about that because I’m like, I don’t want to pick one thing. I love all of these different things and what I did to come to peace with the fact that I see other people getting really great at one craft and finding a lot of success in that, while I’m trying to DJ and then also be a video artist and also be a painter… what I came to peace with is, okay, for me it’s not so much about success at this younger age. It’s more about I really am invested in all these different ideas and by working a little bit in all these different areas, decades down the line is when it’s all going to come together. But I don’t know, that’s just the story I tell myself. For me, I’m really trying to figure out if I should narrow in, in this time that I have. Should I just focus only on making amazing DJ mixes or should I focus on painting? I still don’t know what to focus on and so what I’m really finding is I just have to listen to my body and what really makes me excited is being able to spend a couple of days in Ableton doing a lot of sound production and leaving it for a couple of weeks and spending it doing something else. And I feel like for me, it’s just the creative energy that just flows through a bunch of different stuff and it’s not so much about this one craft. Because I can’t imagine one craft ever satisfying me in the way that just being creative and just moving through different things, satisfies me. So I don’t know the answer to that, I just know for me personally it works really well to be diluted and unfocused. (Laughter)

Amy: Well, but at the same time it sounds like you’re honoring your need for all of these, to fill yourself with all of these different interests. And maybe it feels diluted but when it’s time to output, you can concentrate this into a remix of something that’s unique to you. And as you were describing that, it reminded me, I’m watching this movie about regenerative farming and there’s a way to heal the soil and it’s not a monoculture, it’s by planting many species in the same area and it makes the soil have a more biodiverse microbes and all the organisms and all the composted material that goes back into the soil is more beneficial because it’s more diverse. That’s what you’re doing.

Ari: Thank you!

Amy: You’re filling yourself with many species and becoming a very, very healthy, rich kind of fertile place for things to grow from.

Ari: Thank you, that’s what it feels like, so I think it’s also just like listening to yourself, like society will tell you. Focus on one thing, you just have to listen to what works for you.

Amy: Well, I love that you’re in a space of listening to yourself and listening to what works for you. Normally at the end of this [0.50.00] I like to ask people what’s on the horizon. I don’t even want to ask you that right now because I don’t want you to have to, I don’t know, pick something. But if you had a hope for some unexpected outcome of this time that you’re giving yourself right now, what would that be?

Ari: I think what I’m also realizing is as much as I’ve built community, I think it was very much in service of what I thought was needed. As opposed to thinking about what’s the community that I need. And I am just constantly buzzing with all these different philosophies. And so now that I’m out on my own again, I’m pushing myself more out there it’s kind of like being a lighthouse in the middle of the ocean and just saying, “I’m doing this, is anyone else thinking about these kinds of things?” For me, I think what I would love is just to find more people that are really excited about the things that I’m excited about and just to community with them.

Amy: So you want to go to the lighthouse and be (laughter)… instead of being the lighthouse.

Ari: Yes. (Laughs)

Amy: Or maybe a little bit of both.

Ari: Probably.

Amy: That makes a lot of sense. You’re such a fascinating and I want to say very generous, very thoughtful, gorgeous spirit. I really hope you do find the community that makes you feel full and abundant and fertile and seen.

Ari: You too.

Amy: Hey, thanks so much for listening. For a transcript of this episode, and more about Ari, including images of her work, and a bonus Q&A - head to cleverpodcast.com. If you can think of 3 people who would be inspired by Clever - please tell them! It really means a lot to us when you share Clever with your friends. You can listen to Clever on any of the podcast apps - please do hit the Follow or subscribe button in your app of choice so our new episodes will turn up in your feed. We love to hear from you on LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter - you can find us @cleverpodcast and you can find me @amydevers. Please stay tuned for upcoming announcements and bonus content. You can subscribe to our newsletter at cleverpodcast.com to make sure you don’t miss anythingClever is hosted & produced by me, Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever is a proud member of the Surround podcast network. Visit surroundpodcasts.com to discover more of the Architecture and Design industry’s premier shows.

What is your earliest memory?

Making rice krispies treats with my mom in preparation to watch one of my favorite childhood movies, Space Jam with Michael Jordan.

Hues of Stzair Ecology

Ari in the studio

What’s the best advice that you’ve ever gotten?

My first grade teacher instilled in us to always treat others as you would like to be treated.

How do you record your ideas?

Lately I’ve been trying to archive every idea I’ve written in all my random notebooks and in the note app on my phone, over the years, into one book. It’s really helpful to retrace my steps and study patterns of what have peaked my interests in the past 10 years. While I work on catching up in one book, I’ve also been either doing video or voice recordings of myself just talking and trying to hold on to all my ideas before I forget them. I have way more ideas than possibly have time for, so I’m hoping to dissect them and figure out what’s the essence of these ideas and push further in that direction.

What’s your current favorite tool or material to work with?

Dancing. I’ve always loved dancing but I’ve been finding a new comfort in my body in the past few years and especially the past few months. These days, it feels like at least 50% of my days are dancing around my home, studio, and especially in my car. As I do music production, dancing helps be understand sounds and beats better - i’ve been calling it a sort of beat embodiment as I let my body freely move to the structure of the sounds.

What’s the best book you’ve read this past year?

Best book has to be Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. Especially in reference to me trying to archive all my written ideas from the past 10 years, it can be overwhelming to think about all the things that I want to do. We all can feel overwhelmed by our ambition and the finite amount of physical time on Earth. That book helped me chill out a lot and take it easier.

Infinity Bending series

Metamorphosis.FM

Strawberry Sounds

What might we find on your desk right now?

A bunch of sound equipment, chapstick, hair clip, notes on random pages, scented oils diffuser.

Who do you look up to and why?

Anyone who’s really honest with themselves, and trying their best to figure out how to be their honest authentic selves in this world.

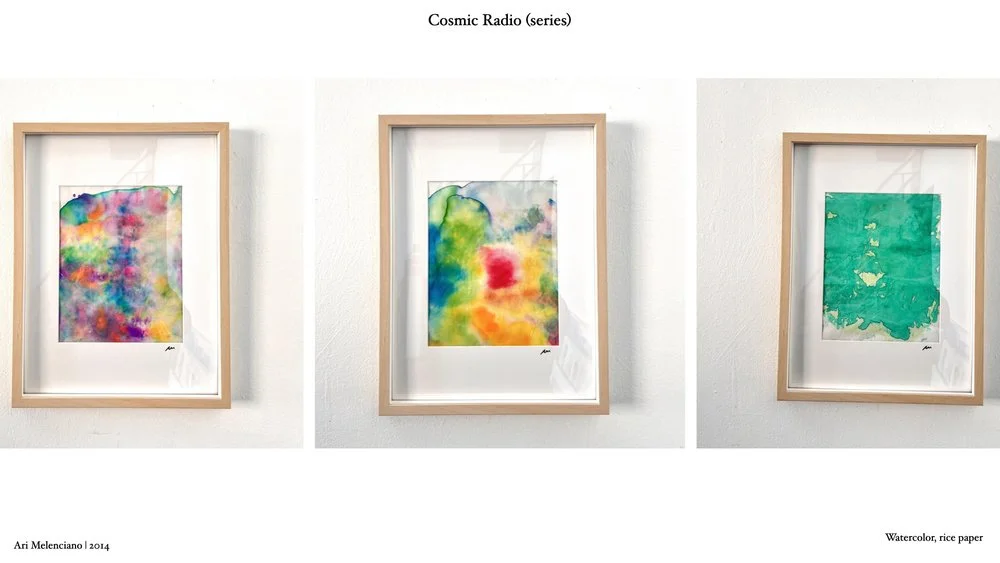

Cosmic Radio series

What are the last five songs you listened to?

I’m obsessed with Ramsey Lewis’ Mother Nature’s Son. I accidentally overhype it to everyone I talk about it to.. I want my work to have that level of nuanced and intricate love poured into and received from.

Where can our listeners find you on the web and on social media?

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.