Ep. 162: Building a Colorful Second Act with Illustrator Yuko Shimizu

Illustrator Yuko Shimizu was born in Tokyo, Japan and began drawing from an early age. As a preteen, her family moved from Japan to the US, a huge culture shock that included learning an entirely new language and navigating social norms in 7th grade. This experience gave her an even deeper love for drawing - something that transcends any language barrier. After college, Yuko spent 11 years at a prestigious corporate PR firm in Japan before she decided to pursue her lifelong dream. At 34, she enrolled in art school in New York City. Since then, she’s received numerous accolades for her beautiful illustrations. A staunch supporter of going after what you want, Yuko certainly doesn’t regret any choices she’s made to draw a new path forward for herself.

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and This is Clever. Today I’m talking to multi-award-winning illustrator and artist Yuko Shimizu. Born in Japan, but now based in New York city, in Yukos’ 20 year career of illustrating she’s had work in The New York Times, TIME, Newsweek, The New Yorker, WIRED, done covers for DC Comic, Penguin, and Scholastic, and advertising for Apple, SONY, Paramount, MTV, Nike, and Target, to name a few. She is a two-time Hugo Award nominee, has won more than 15 medals from the Society of Illustrators, and was recently awarded the Caldecott Honor. All that and, she also teaches at the School of Visual Arts. But, here’s a twist… Illustration is her second career. After graduating from college in Japan, Yuko spent 11 years in corporate PR before making the bold choice to reinvent her career at the age of 34 when she moved to New York to get her Master’s in Illustration at SVA. It’s a great story, here’s Yuko.

Yuko Shimizu: Hi, my name is Yuko Shimizu, I am an illustrator. I’m originally from Tokyo, Japan, but I’m based in New York City. Why I do it? (Laughs) I think art is a calling. I loved drawing and painting ever since I was a child and I’m the happiest when I’m creating artwork and I feel I am very fortunate to be able to do this for a living.

Amy: Well we’re all fortunate that you get to do this for a living (laughs) -

Yuko: Thank you!

Amy: I always like to go way back to the beginning. You were born in Tokyo. Will you tell me all about your childhood, your family and your youthful fascinations?

Yuko: I think I come from a pretty typical middle, upper/middle class, Japanese family. Father worked in corporate environment and my mom stayed home and raised me and my older sister, which is like very typical. I started drawing, ever since I can remember, but then actually I don’t remember the first time I drew. My mother later told me, one day when I was like two, I drew a really wobbly circle and line on the edge of newspaper with crayon and said, “Mom, I drew a balloon.” And then I kind of never stopped since. I did stop when I grew older, but as a child I always drew. I was never athletic, so often after lunch older kids go outside and play dodge ball and stuff and I was so not good at sports and dodge ball hurt. So why -

Amy: Dodgeball is cruel!

Yuko: Dodgeball is cruel; I don’t know how it is now, but when I was a kid, that was like what kids in elementary school loved to play. There were always, like maybe five kids out of class of 30-40 who would rather stay inside after lunch and draw or read. I was one of those kids. Yeah, so that’s how things started.

Amy: Just out of curiosity, did your mother or father have any artistic hobbies or inclinations? Did your older sister draw as much as you do or were you kind of an outlier in your family?

Yuko: I think it’s very common for Japanese people to draw and even if it’s not really, like their biggest hobby. I don’t know, I grew up surrounded by the first big boom of anime and manga and so in Japan, now it’s popular everywhere, but back in the 60s and 70s when I was growing up, that was the first boom and a lot of kids drew mimicking comics. Not necessarily my parents were into art, but my mother made all her clothing and all mine and my sisters growing up. I sometimes ask my father, draw me a samurai and he was able to do it. I don’t know how good he was, but I think it’s like pretty common for Japanese people to draw, especially art classes were mandatory up to high school. Which is very different from how it is in the US. Maybe it’s part of the things people did, but it’s not that I had any artist in my family.

Amy: You did say that it’s different from the US and you would have some personal experience with that because during adolescence you and your family moved to Westchester County [0.05.00], New York, for four years.

Yuko: Oh my god, you researched! (Laughter)

Amy: You can’t hide from me Yuko, you can’t hide! But I am curious about what that was like for you, culturally, emotionally, socially, developmentally, I mean that’s a big culture shock, that’s also just a big transition and a sensitive time of life. How did that go for you?

Yuko: So it was a huge culture shock. I was 11 turning 12 when I moved and in Japan, I don’t know about now because I haven’t lived there in more than 20 years, but back then at least, English education started in middle school. That’s 7th grade and I moved to New York in 6th grade. So the day before I started elementary school, 6th grade there, my mother sat with me and told me, you have to memorise all the alphabet tonight, which I don’t think I can do… You show me Arabic or Hugo, or something, like yeah, you learn it overnight. Kids brains are pretty flexible, so I was able to learn all the alphabet overnight. And she told me, “Hi, I’m Yuko, nice to meet you,” and, “Where is the toilet?” I think those two things, you have to memorise these two things.

And I was sent to school, and you could easily imagine, the first year or year and a half was a nightmare because I have to learn the language and I also have to do school work and I don’t even know what the homework is because I don’t understand what the teachers were saying. So I don’t think that was the hardest thing I ever experienced in my life, but what’s hard and what’s not hard is based on where you are at. At age 11/12, my life in school was pretty comfortable. I was pretty popular because I can draw in Japanese [** 0.07.30].

Suddenly I’m in a foreign land, I don’t have any friends, I don’t know what the hell is going on in school and then have to adjust to it. So yeah, a year and a half, I feel like if I was able to get through that, I can get through anything. And I know, I’m saying this knowing there are people who have a lot harder experiences, but not to compare anything. In my life, at age 11, that was definitely the hardest thing and you know, what’s funny is, I was one of the tallest in school before I left. I was like 5.2 and at that age, especially boys are still short, so I was one of the tallest.

And I was growing and I moved to the US and I completely stopped growing, and then I also am the shortest in my family, which is really weird because I’m shorter than my mother. I read or heard on the New Segment or something, if a child experiences very traumatic situations, they can stop growing.

Amy: I totally believe that! I think the stress of the situation impacted your growth.

Yuko: I mean, not that I went through a Civil War or anything, but in my mind it was like the most traumatic thing. Yeah, I kind of stopped growing and it took me two/three years to get really comfortable in school, but I always felt like I’m Japanese and I’m very different. And then I spent four years and my family went back to Japan and I came back to Japan, holy crap, people consider me as American, which I am not. So ever since then, I’m at peace with this. Ever since then, I went back to Japan when I was like 15/16, so until now, 40 years later, [0.10.00] I still feel like I’m neither Japanese or an American.

It was a struggle for me, especially trying to fit myself back in as a [**] in Japan and kind of sticking out in a society who don’t like people sticking out. But after I came back and kind of… As an adult, I’m like, okay, I don’t need to be an American, I don’t need to be a Japanese, I’m kind of half and half, which I’m okay with that.

Amy: I can understand though how in those formative years, sticking out in the US as being so Japanese, did you use drawing as a way to communicate? Drawing can sometimes be that thing that transcends the language barrier.

Yuko: Initially when my English wasn’t great, what I excelled in, especially I already said I wasn’t athletic, right?

Amy: Yeah.

Yuko: So what I excel was like, it’s kind of stereotype, in maths and art and I’m not good as maths, I never was, but maths, numbers are universal, right? If I can listen to, like understand enough what the teachers were teaching, what we’re supposed to learn, it was the easiest thing because I don’t have to memorize new terms, I don’t have to express myself in the language I don’t understand. So I think the teachers thought I was one of those Asian maths genius (laughter), I’m talking about elementary school and early middle school.

So I excelled in that and I also drew more because drawing doesn’t need languages. I still feel I’m super lucky to be working in the field of art because it doesn’t have borders. The pictures speak the language of anyone. It’s a universal language, most of my clients are in the US. I sometimes work with Japanese clients, but not much. This weekend I’m working with a French publisher, but because I don’t have to write or read, I just have to communicate with my client, which can be done in English and then create the artwork French people do understand. But of course they do because it’s just pictures. If someone is writing or a novelist, people outside of their language cannot read it or understand it unless the translation comes out.

But visual art, like illustrations, artwork, paintings, these are the universal language and I feel very, very fortunate that I happen to, it’s not my choice, right, it’s kind of art chose me, I didn’t choose them. And that happened to be something that speaks the language of the world.

Amy: Well, so back in Japan after a four year formative stint in the United States and you’re feeling neither Japanese nor neither American, but also having stuck out in the US and sticking out now in Japan, that’s a lot of exposure for a young person -

Yuko: Yeah, yes.

Amy: Were you feeling compelled to hide or were you embracing being different? What was back in Japan like and then how did you chart your course towards university?

Yuko: Again, things, I’m sure things are changing, but at the same time Japan is an island nation. The border means there are seas in between and the mentality is very different from the US, it’s a melting pot, or Europe or Latin America, or anywhere else, there are borders. So it’s very homogenous, it’s becoming more international every time I go back to Japan. But then there is a feeling, Japan is Japan and it’s a separate entity. And sticking out there is really hard. And whenever I mention this, people say [0.15.00] something like, oh, but what about this person or what about this art, or what about that artist or what about that film director.

Yes, but there are exceptions to anything. If someone says, what about [**], the world famous fine artist, yes, it was probably extremely difficult early on for him to be him and then in Japan and then he stuck with it from the start and not many people can pull that off, especially as a woman. It’s not an easy place… Japan is not an easy place to live as a woman and unfortunately still is. I ended up trying to hide, especially in the beginning, in high school, like college… High school I went to this weirdo high school where students either are not Japanese or Japanese people who grew up abroad, for whatever reasons, and came back and they don’t have any traditional schools to fit into. So it was very comfortable. I’m still close friends with many of my classmates and whenever I go back to Japan I hang out with them, have dinners and coffees and things. But my college was especially, very Japanese and especially like having lived abroad, being able to speak a language outside of Japanese and the country being the female is not, like still it’s like 20-30-40 years behind how women are perceived in the US. It does not make my life easier when people knew my background.

So I tried my best to hide it, but it’s not that easy because I might say something different, or back then it’s like, like 80s, if there was a big hit show in TV, every high school kid, college kids watch that and if you didn’t, you were either really weird or you are hiding something. So it’s funny to think about it. Now things are so diverse, even TV shows. It’s Squid Game is popular, it’s okay if you didn’t watch it, but back in the day, TV was just like five/six channels on the TV set -

Amy: And without the internet you couldn’t watch Japanese programming in the US or vice versa.

Yuko: Right, exactly, so I knew about this like super popular TV drama, about high school and everyone watched it and during college, people talk about, oh yeah, that show. I never ever watched it and that gave away, and I couldn’t win because it’s either a weirdo never watched that famous TV show or you lived abroad.

Amy: That’s interesting, that’s actually really… Back before the internet there would be all of these cultural touch points that if you weren’t local to that proximity at the time that they were happening, then you missed out on them and then that becomes like a big missing piece of your quilt that everyone at some point can see. I can see that that would be difficult to hide because everybody has these references that you don’t have, so that’s interesting that that would show up as something that felt like exposing you as being… I guess more international than you wanted to feel in the moment because it wasn’t comfortable to stick out.

Yuko: Yeah, exactly.

Amy: So you studied at Waseda University with a major in faculty of commerce and graduated as a Valedictorian, which is very high honor, applying yourself. But I don’t know what faculty of commerce means and I don’t know how you got there or why you made that choice. Can you kind of explain that?

Yuko: So yeah, it’s like, looking back it’s really weird, right? I didn’t pursue art because I did want to go to art school, but I [0.20.00] wasn’t sure I wanted to go to art school in Japan. And my parents are really against, first of all, art school because what do regular parents who don’t have any artists in the family know about the life of the artist. It’s like a joke. They think of Van Gogh, you’re poor, your brother has to send you the paint and you go crazy and kill yourself (laughs) because you’re poor.

So they’re like, don’t’ ever pursue art and I was just a 17/18 year old with a hobby of drawing and I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. A lot of kids in Japan draw, and draw quite well. So I’m like, I’m not that special and I’ve been told that. And also I felt like maybe it’s a phase, like I wasn’t sure, like all these mixed feelings. I was also not confident enough to say, this is what I’m going to pursue.

My school, like high school for weirdoes because we all experienced some kind of trauma, having dropped off in a foreign land. I lived in New York, that’s kind of, like I had it pretty good. But that’s when Cold War was still going on and I had two classmates who came back from the Soviet Union and another one… And they had the same name, funny, two boys. One came back from the Soviet Union and one came back from Afghanistan because the Soviet Union invaded it.

So it’s kind of like, on top of having, have to live abroad for whatever parents reasons, I don’t know what sent their families to Afghanistan and Soviet Union. On top of living in a foreign land, having have to learn languages and they have to experience war and the height of communism, right? But I think what we all had was because of the circumstances we were dropped off in, we learnt to kind of work hard. Because you have to learn the language to survive and you have to do that to be accepted to the local schools we were in. I don’t know if it’s a Japanese mentality or it’s universal, but we’re constantly told by parents, especially as minorities, that maybe your classmates have never met Japanese people before and how you behave, how you do well or not well academically, your classmates will judge the whole Japanese population according to how you… It’s such an Asian parents thing. (Laughs)

Amy: A lot of pressure!

Yuko: Yeah, yeah, yeah, but I think because of our school, although there are a lot of weirdoes, they’re cool and fun, but they excelled academically because of, I think our previous experiences.

Amy: Needing to rep all of Japan in foreign countries by excelling.

Yuko: Yeah, yeah. That’s a lot of pressure. Now looking back, but that was the norm. The school did quite well, so a lot of the good schools had slots for our graduating class, like 1% can come to our schools, whatever department, whatever department. So there was an open up for Waseda Universities School of Commerce, which is basically like a business major, but more of a, not the practical business, but more theory.

So there are economy classes and there are accounting classes we have to take, like constitution and those classes, to build the knowledge to be a businessman. But at the same time the school [0.25.00] was pretty well-known for their advertising majors.

Amy: Okay.

Yuko: They didn’t call it majors, but concentration in advertising and I thought, okay, I’m not sure what I wanted to do, but I want to do something creative and then I wanted to make my parents happy and I felt like advertising, going to school, commerce in a really good university in Japan and make them happy. Also I can do something sort of creative in the most… The most creative in the most practical world. And that was kind of the reason why I went there.

Also the funny thing was, back then the Manga Club, it’s like outside school activities, but it’s part of school, was really, really huge in that university. And a lot of the famous comic artists came out of it. There was a literature major and literature major people tend to be a majority of the circle, of the comic creators. That was one of the reasons I went. It didn’t work out for me. I always wanted to be a comic artist, growing up, but I think I only felt so because we grew up reading and mimicking manga.

It took me a while to realize, I’m not interested in telling stories with panels and pages and coming up with stories that is long enough to fill pages and pages. I was only interested in creating single images. So that led me to illustration ultimately, but back then I was very much interested in comics and those funny reasonings brought me to the university, I ended up studying.

Amy: Okay, so you got a degree in basically the theory of business, part of your appeal for that university was the celebrated manga and comic book artists that (laughter) were known for that school. Okay, this is all starting to add up. I know that eventually you went back to school to study illustration, but before that you had a professional first life in advertising and PR. Talk to me about this major chapter of your life and how it influenced you and your eventual decision to go back to school to study illustration?

Yuko: Yes, after I graduated I got a job in corporate PR department in a big corporation in Japan. But you would never know the name… Recognize the name of the company unless you are Japanese. But they do kind of big general tradings all over the world. It’s a pretty big company in Japan and I got accepted into the PR department by luck. It was a good choice, considering my background in advertising and marketing.

But in Japan it’s mostly you get a job in a company and not by job descriptions. So they really have this tradition of having employees loyal to the company and people tend to move around and understand it, become generalist of the company. That’s like a whole tradition of Japanese corporate culture. I don’t know why I never moved into different departments. It’s not that common for someone to stay in the exact same department for more than 10 years. I was there for 11 years and a bit.

But it was very lucky because it worked out with my background and interests and like I said, I wanted to do something creative [0.30.00], at least creative in the practical field and that kind of fulfilled my desire to do so. I thought I wouldn’t last from day one because I quickly realized I’m so individualistic. I think I learned this in the US, or maybe I always had it, I don’t know. I have my opinions. And that doesn’t work well, especially in a corporate culture in Japan.

So my job was actually very interesting. I was able to assign advertising and sometimes work with illustrators, which always I envied and wanted to be on the other side. Or corporate, editing corporate brochures, because the company is so big and spread around the world and they had like an inhouse company magazine to talk about what’s happening in the company and who are the people who are working. It’s a highly distributed magazine and I was editing that at some point.

So it was interesting enough, work-wise, but the corporate culture wasn’t for me. But then I still didn’t know what I really wanted to do with my life and it took me a while, maybe around age 30. It’s hard to quit a job where it’s stable and you will get the pay check every month. So I stuck around a bit and around age 30, then oh my god, I’m not a kid anymore and do I want to just stay here and get old and retire and live off of the retirement (laughs) -I thought that was not what I wanted to do. So I kind of started really thinking what I should be doing for myself, to make myself happy and have a fulfilled life because as cheesy as it is, we only live once.

Amy: It’s a cliché, I get it, but it’s true.

Yuko: It is so true, if you think about it. That’s when I started thinking about, like crossing out the options. Initially I thought, I want to go back to the US, I want to go back to the East Coast and so I don’t feel like this weirdo who is not Japanese and always felt like an outsider. And so initially I thought, maybe I should get an MBA, because that made more sense. I was in corporate, I majored in advertising and marketing, maybe I can do advertising MBA, I seriously thought about it.

And then I talked to my really good friend who immigrated to the US and she became an engineer. I met her when I was living in New York and she’s Japanese. And she’s like, you know, she gave me the best advice. You know, in the United States, going back to graduate school means you get out of college, you do whatever you need to do and you realize what you really want to do for the rest of your life. And when you’re committed, that’s when you go to graduate school.

And so if you want to do advertising for the rest of your life, it’s fine, but think it over, what do you really want to do. And I think that was the best advice. And so the process itself of coming up with going to art school was long, but long story short, I really went soul searching. What is one thing I really wanted to do and never do? It’s to pursue art.

And I also never really wanted to go to the Japanese art school [** 0.34.38]. So okay, if I go to the US for school, even as a non-US citizen, you can get one year of work permit. And then that’s your chance to get a work visa and stay here. [0.35.00]. It’s not really as easy to move to the US and just restart your life. And going back to school made the most sense. So that’s how I ended up coming back to New York.

Amy: So you did mention you had to do some soul searching and you have your opinions and those opinions maybe didn’t sit so well in corporate culture in Japan. Was pursuing art also… Did that also feel like an avenue where your opinions would be valued instead of treated as a threat?

Yuko: Yeah, I guess, but then I also didn’t want to be an artist in Japan. At that point I wanted to pursue illustration. I knew comic wasn’t the thing for me but there’s a very particular way that illustrators create things. They like cute and pretty and I was never into either of those.

Amy: Yes, I’m getting it now (laughter).

Yuko: And also when I went back to art school I was 34 already, so if I’m trying out the second life, first of all, Japan did not back then, appreciate the second life. You get a job right after college and you pursue it for the rest of your life. That was kind of the life path. So doing your life over wasn’t easy. Nobody goes back to school, art school at age 34, at least back then. There are so many reasons Japan wasn’t working out for me and I also wanted to go back to New York where differences are appreciated.

Amy: Was it re-traumatizing to move back to New York in your 34s or did it feel empowering because at this point you are consciously choosing this?

Yuko: It was both. So unlike some other classmates, some of them came from Japan and they’re much younger and that’s cool. But they struggled with language. My English wasn’t great. I was only here for four years, but I was okay, I understand everything everyone says how I express myself wasn’t perfect, but I can say whatever was on my mind. That was the English level I had. I realized living here as an adult by myself, and taking care of everything on my own was much harder than I thought.

I thought it would be easier because I’d lived here as a kid, but the kid’s experience and adult experience is completely different. There are a lot of obstacles that I faced. First maybe year or two was hard but then luckily I came back as a student, so you’re surrounded by friends.

Amy: You have a community.

Yuko: Yeah, you have a community, so that was easier because often if you move as an adult, the hardest thing is to make a community of friends. And to get to know new friends as an adult in a new environment can be difficult, but school made it so much easier for me. It was definitely both traumatizing and extremely freeing.

Amy: Oh, I’m feeling it. It’s like such a scary and exciting chapter of your life, but it also must have really reinforced your own resilience after getting through that. You make the conscious choice, you get here, it’s harder than you thought it would be and triggering in many ways and yet it’s something that you want. So you work your way through it and then as you sort of establish a degree of comfort, what comes with that is also a degree [0.40.00] of agency and ability to move through the world in a way with a trust and confidence that you know how to do it. And that’s pretty cool.

Yuko: Yeah, I’m glad. One thing I’m really happy I did, is I moved here and like don’t get me wrong, it wasn’t all smooth. Especially during school, right after I graduated and I started working, I sometimes did wake up in the middle of the night and holy crap, what am I doing?

Amy: (Laughs) I still do that!

Yuko: Yeah, I still do that too, but my friends are all settling down into their adult life, right? Maybe they have family, raising kids, buying homes, like they’re doing adult things, while I’m living with roommates and having these roommates problems and I was living off of my savings. I had no money. My dream was to go into Starbucks and buy a coffee without worrying about the $4/$5 I drop. That was my dream. And I remember, I went to some lecture as an undergrad student. There were some graduate students in the mix of audience and one of them was holding a Starbucks cup.

I was like holy shit; this person can afford Starbucks (laughter). And whenever I woke up in the middle of the night, what I tried to do to calm myself and I told this to my students too because I teach and I have students who are in the similar situation, right? And they worry, can I stay here, I want to stay here and work, can I make an income okay, like all these things. And then I tell myself, at least I’m in New York doing what I really wanted to do, so the rest will figure itself out, if I work hard enough.

Amy: Oh.

Yuko: I still feel the same, kind of.

Amy: I do too, I think that’s really good advice. It’s like you’re not promising anything and you’re not guaranteeing that uncertainty won’t be there, but you are saying, consider that you’re laying a foundation that is intentionally what you want to do and trust that you’ll be able, with hard work and some creativity, the rest will, not fall into place without effort, but that you will be able to navigate it and make the life that you want.

Yuko: Yeah, I think so. I mean what are the other choices right? Other choice was not coming here and not pursuing art and being in a corporate situation where I hated, but like with stable salary. Oh man, what would it have been if I had pursued art and then getting older, thinking of that. That sounds really sad.

Amy: That’s torture yeah.

Yuko: Yeah, that’s torture, but a lot of us do it and I mean I did it for a long time right? Thinking about what if I pursued art and there’s no answer for that. There was only questions, but I could have failed, I could not have been able to get a work permit, I would not have been able to get any freelance illustration work and have to do something else, god knows what. But at least I tried and then I can move on, right? There’s no more asking myself, what if I did it? I think it’s really important if we wonder strongly enough about the things we haven’t done, we should do it. And if we do it and things don’t work out, at least you did it.

Amy: Yes!

Yuko: And I think there are a lot of things we’ve done, things didn’t work out, for whatever reasons, and we kind of move on and not think about it much because we’ve done it and crossed it out. But things we regret [0.45.00] are the things that we didn’t do and after I did this, and you know, like some people might say, you’re lucky, you did it and it worked out. But then also what people can’t forget is I can fail tomorrow. Nobody wants to work with me tomorrow and I can still fail, but at least I’ve done it and I think doing it, something that we feel strongly about is very, very important.

Amy: I agree with you and even though you could fail tomorrow, I don’t think you will because there is such a powerful drive underneath what you are doing. And because you’ve also now, built up a pretty solid professional track record, since 2003 you’ve been illustrating professionally and making quite a profound body of work about some tough subjects and racking up awards and accolades including a Caldecott Honor recently, for The Cat Man of Aleppo, congratulations!

Yuko: Thank you so much.

Amy: I’m wondering now that you’ve sort of built this life for yourself and you’ve worked really hard to build it and you’ve put yourself in really uncomfortable situations to get here, do you value it to the degree you thought you would and do you feel any sense of peace in the work that you’re doing?

Yuko: I had a friend staying with me two weeks ago, two weekends ago and we’re really good friends. She is in the super high end web design world and she’s a designer, much younger, but extremely established. And then on the weekend, Saturday we went out and I was like, oh, I’m thinking about the deadlines and she’s like, you’re so established, why do you work hard? I work hard, but I’m over working all the time and I want weekends off, I want nights off and you should do that.

I get it and then like, yeah, I get it, maybe I still work too much but then I kept thinking about what she said and what I realized is if nobody is paying me money to do profit 0.47.45], I still do the same thing, you know what I mean? Not to degrade her work, she does amazing work, but I don’t think if she’s left alone, web designing is what she would do on the weekend when she has free time. So being a visual artist, yeah, it’s my job, it’s not just my job, it’s my passion and I can slack off with like I care about what I do and what I create and I think… I’m just really fortunate that I found my calling and I’m being able to sustain my life with my calling. I want every day to be different, in terms of art, right? I want every day to be different. Of course I want breaks. I was just in Portugal for a conference, but I only had two hours that I have to commit to, do lectures and workshops and things. The rest of the time it’s like a break, I appreciate breaks, I appreciate travels. But if I’m left alone, I will create and one of the reasons I needed to quit my job was, every day started to feel the same and being an artist, every project is different and that keeps me going.

Amy: So speaking of every project being different and it keeping you going, I’m super curious about your creative process. I am not an illustrator, obviously, but I also have never thought [0.50.00] in 2D or in drawing, sketching has never even been my strong suit. So Can you give me an overview of your creative process and maybe how ideas start to shape in your brand and then you got them out.

Yuko: Yeah, so often people who create work from nothing, right, that’s what we do (laughs) - From outside it looks like I don’t know, it’s like a magic, like we might have this lightbulb in our head and that lights up and we get inspired and create cool things, but it doesn’t really work that way.

Amy: (Laughs) It’s a lot more struggle than that.

Yuko: A lot more struggle than that and also a lot more structure and logical than what people might think. Of course everyone works differently. I can only speak for myself, but I do not have lightbulbs. Sometimes I do in a very, very lucky situation, but most of the times I don’t. So if it’s a work project, so I’m working for a French magazine right now, it’s a cover and they approached me, do you want to do this, this is the overall view of this idea. And like, oh, that sounds interesting.

So first of all, does the project feel like something that is suitable for me? When it’s not, I will tell them, there are people who are more suitable for this than me. First I have to get excited, or excited enough. And then I get excited, okay, give me material. It’s a French magazine, so I didn’t read the article because I don’t read articles, but I ask questions about what it is and he explained to me what the article was about and sent me some photos to accompany the article.

So usually I read articles. And from there, okay, I need to learn a little bit about a subject, in this case it’s a person, or the group of people, so I Google search about them and look at more photos and maybe read about them to understand. The more information I accumulate, it is better for me to come up with ideas. So ideas don’t come from thin air. Ideas come from research. The more I know, the more ideas I might be able to get. So I start thinking about what’s visual, what do I need to say in terms of this specific article.

And then I draw, like really quick sketches onto the paper that I might be the only person who understands it, but it’s okay. I call it ‘brain puke’ (laughter) thinking on the paper and a lot of things come out not right, but in order to get to the right place. Everything needs to come out. And then after a while doing that, maybe I have two/three ideas that may work. And then I refine compositions for those ideas. And then make it into sketches, the client sees and understands what is in the picture. And then I send that out and explain why I did this and what it means and how that relates to the article they sent me.

And then they say, sketch one or sketch two or whatever, and like, I like this one and I put in the [** 0.54.04], so that’s approved, and once it’s approved, I draw with ink and brush on watercolor paper and then scan that in and color it on Photoshop and the final file only exists as the digital file. I do this funny process, nowadays all my students are starting everything digitally. Especially on the iPad because I think the pandemic accelerated the use of iPad because they can work anywhere, in a small space and it’s less stressful.

You don’t need scanners and multiple different things; you don’t need a lot of space. You have everything on one iPad. [0.55.00] So that’s how it is now, but in my case I still draw because drawing is my passion and colouring is my work. But the piece won’t get finished unless it’s coloured, so that part is done on a computer, but the fun part needs to be done by the most fun process for me, it is drawing.

Amy: That’s your first language.

Yuko: Yeah, it is.

Amy: I love that you explained that for me, I was there with you through every step and I feel like I really want to see some brain puke, if (laughs) you would share one of your brain puke -

Amy: Pages, I think I would be so fascinated in that.

Yuko: Sure.

Amy: In terms of your professional development, do you have criteria for… I mean you mentioned before undertaking a project, you need to feel that it’s right for you and you need to be excited about it. But is some of that informed by the relationships, by the people. Is there some way that you choose to work with certain people or companies or is it mostly project based?

Yuko: Both and in terms of people, I didn’t become where I am by myself. People support me. Especially in the beginning, people took chances on me and people are nice to me. I was starting out, I had no money and they gave me jobs. So whenever some of my early clients come to me and want to work with me and the budget is small or whatever, if it fits in the schedule, I do it because the relationship is very important and the fact that they help me start my career is very, very important for me to… Sort of payback.

Amy: Yeah, that’s nice, that’s honoring a long term relationship, even though you can afford Starbucks now -

Yuko: Yes (laughter).

Amy: You still haven’t forgotten where you came from -

Yuko: (Laughs) I know.

Amy: Those relationships, I think, the older I get the more I value the relationships that have this length to them. Maybe they’ve not been that close, but they’ve existed through different chapters and they sort of have a stability to your interaction with them that’s kind of comforting to know that there are posts in the world that you can always stop at and enjoy a familiarity with people. That’s really important to nurture those in your life, otherwise you’ll always feel unmoored.

Yuko: Sometimes, and probably early on I didn’t quite understand it enough and so I stress this to my students often that at the end of the day, illustration business is people business. You’re dealing with people and so if you do incredibly amazing work, but you’re an extremely difficult, self-centered person, then the clients never want to work with you. They want your art, but they’d rather not go through what they have gone through. So I always tell them, work hard, be nice (laughs), which is very important.

We forget and in art school, generally, they’re really good at teaching art, and how do make art but making art, if you just want to make art for yourself and you don’t have to worry about making a living, do whatever you need and you don’t have to be nice, whatever. But if you want to be working [1.00.00] in the field, at the end of the day you have to collaborate with people and they’d rather work with someone who is really nice to work with and the work is good, but not incredible, if getting an incredible work meaning they have to put up with so much.

So that’s something, like in the beginning we kind of focus too much on art work and we don’t understand, but we start understanding. I try to tell, repeat to my students that’s how it is.

Amy: And I think just to recap your earlier mention of you only live once, I think after you’ve been working professionally for a while there becomes this real imperative to work with people that you want to work with, who make the process enjoyable. Who you want to support because they appreciate it and they want to support you in return, like that reciprocal relationship is so important, because it’s what adds joy to the process and the process is what you fill your days with.

Yuko: It’s still some projects come easy and some projects are really, really difficult, for whatever reason, we can’t avoid it. At least we can try to be nice, right? (Laughter)

Amy: It’s so important and everybody needs that reminder now. There’s a lot of weird acting out that’s happening in the wake of the pandemic because people have been cooped up and suffering through extreme anxiety and if we just are all extra nice to each other, I think we can mitigate some of that.

Yuko: Totally agree, totally.

Amy: How would you like your life and by that I mean all aspects, your personal life, your professional life, how would you like it to evolve over the long term?

Yuko: That’s an interesting big question - As I said, my life as a visual artist is not… I mean of course I do work and then I do need certain separation from work and life, but it’s intertwined a lot more so than maybe other occupations. So I will still… I might make different things, but I will still make art even when nobody is assigning me work. So that’s part of my work, but it’s part of my passion and private life. It is hard for me to divide, but you know, I would love to make, create, generate more of my own projects and I’ve been saying this for some time.

But I really want to illustrate Aesop’s Fables as a book and I already have been talking to a small publisher who funds everything through Kickstarter and makes beautiful books. They’re like, we’re on board, you just have to do it… It’s really hard, especially through the pandemic I’m working from home and everything gets blurred, right? I feel like I’m working all the time when I’m not sleeping. Right now, because everything is so uncertain, I might be taking on more work than usual because, prepare for whatever might come, if bad things don’t come, at least I have something that I feel comfortable about.

But eventually I would love to go back to the studio and now I’m working from home and tackle on the project… Like I’m an illustrator and people tend to think illustrators, when we do our own things we make fine art. Some people are like that and maybe I’ll be like that in the future, god knows. I’m an artist and I would love it both as an artist. But I also love the idea of being an illustrator. So make my own project, like Aesop’s Fables and in the perfect world it’s probably not that easy.

But if I get to illustrate [1.05.00] all the stories with one picture each, that would be years of work. That might be, things like that might be a fun thing to do. Regardless about me working or not working, I’ll be creating and I would like to create more of my own initiated projects. And I love to travel and I love to travel and see the world and I will also love to… Like use my artwork to do more good. Whatever that means in the broad sense, not just charity work or sell drawings to raise money for non-profit of my choice, yeah, those things I do, but help next generation of artists in whatever way I can. One is teaching - Like all these things. As you know, the social media sphere has gotten very toxic, especially over the pandemic. I guess because we’re glued onto the phone because at some point we couldn’t even go outside, right? And the frustration and anxiety comes out as attacking other people, but like you said, if we all try to spread the positive, it will be so much better world. It’s true; people who have bigger social media presence tend to get attacked more. I don’t have gigantic following, but I have a big enough following and I sometimes do get social media attacks. I would like to use my platform to spread positive more than negative. On Instagram, what I like to do when I have a lot of mental space is to give advice to people who want to be an artist or who are starting out.

Because I can teach my students, but they’re maybe only 30 in total each year. In social media I get to talk to a hundred thousand people if they want to hear what might help them. Also what I want young artists, struggling artists to know, the field of illustration, of visual art is not a zero sum game. Looking at artists attacking artists, I feel like a lot of people think, if I don’t get that job, they will get it. There is a pie and a limited amount and some people took the big chunk and there’s nothing left for them.

But it doesn’t work that way. If the people who are only working in the field do great jobs, then a lot more people, like random audience, I’m not talking about artists, think oh, it’s cool to work with illustrators because our brand or whatever, looks cooler and then they want to work more with artists. And it’s not a pie, it’s something, like universe, it spreads. But in order to spread, someone like me who is considered established in the field and others who are doing well, we have an obligation to do better and by us doing better, it helps the newcomers.

And for the newcomers who are freaking out about the pandemic or trying to get their foot in the door, we, not just me, but we want them to know that we’re working so there are more projects for them.

Amy: Right, it is not a finite pool from which all artists are drinking from.

Yuko: No.

Amy: And in fact, the more that art is valued [1.10.00] and recognized as also commercially viable, the bigger the pool becomes and the more room there is for everyone to get in and splash around and do their thing and then the world itself becomes more vibrant and lively and more beautiful and full of texture and color and illustrations and niceness!

Yuko: I truly believe so and it’s not my fantasy, it is really, really true.

Amy: I am with you, 100% and -. I’m grateful for you, out there, the edge of illustration, making the pie and the pool and the universe just bigger and better for everyone. (Laughter) Thank you so much for sharing your story Yuko, this has been so wonderful spending this time with you.

Yuko: Well thank you Amy and thank you people who are listening, I had a great time, having conversation with you.

Amy: Thank you for listening! To see images of Yuko’s work and read the show notes, click the link in the details of this episode on your podcast app, or go to cleverpodcast.com where you can also sign up for our newsletter, subscribe to Clever on Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you would please do us a favor and rate and review - it really does help a lot! We also love chatting with you on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook - you can find us @cleverpodcast. You can find me, @amydevers. Clever is produced by 2VDE Media with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit airwavemedia.com to discover more great shows. They curate the best of them, so you don’t have to. Clever is proudly distributed by Design Milk.

Photo by David Byrd

Yuko as a child

Yuko during her college days

What is your earliest memory?

That I was in kindergarten and a teacher asked what we wanted to be, and many girls (remember, it was 1960s Japan) said “pretty bride” and I thought to myself “girls, bride is not an occupation”, and said “I will be a painter"

How do you feel about democratic design?

I honestly don’t know what that is.

What’s the best advice that you’ve ever gotten?

If you work three times harder, anything can be accomplished. My mother said it, and she said she has no recollection of it.

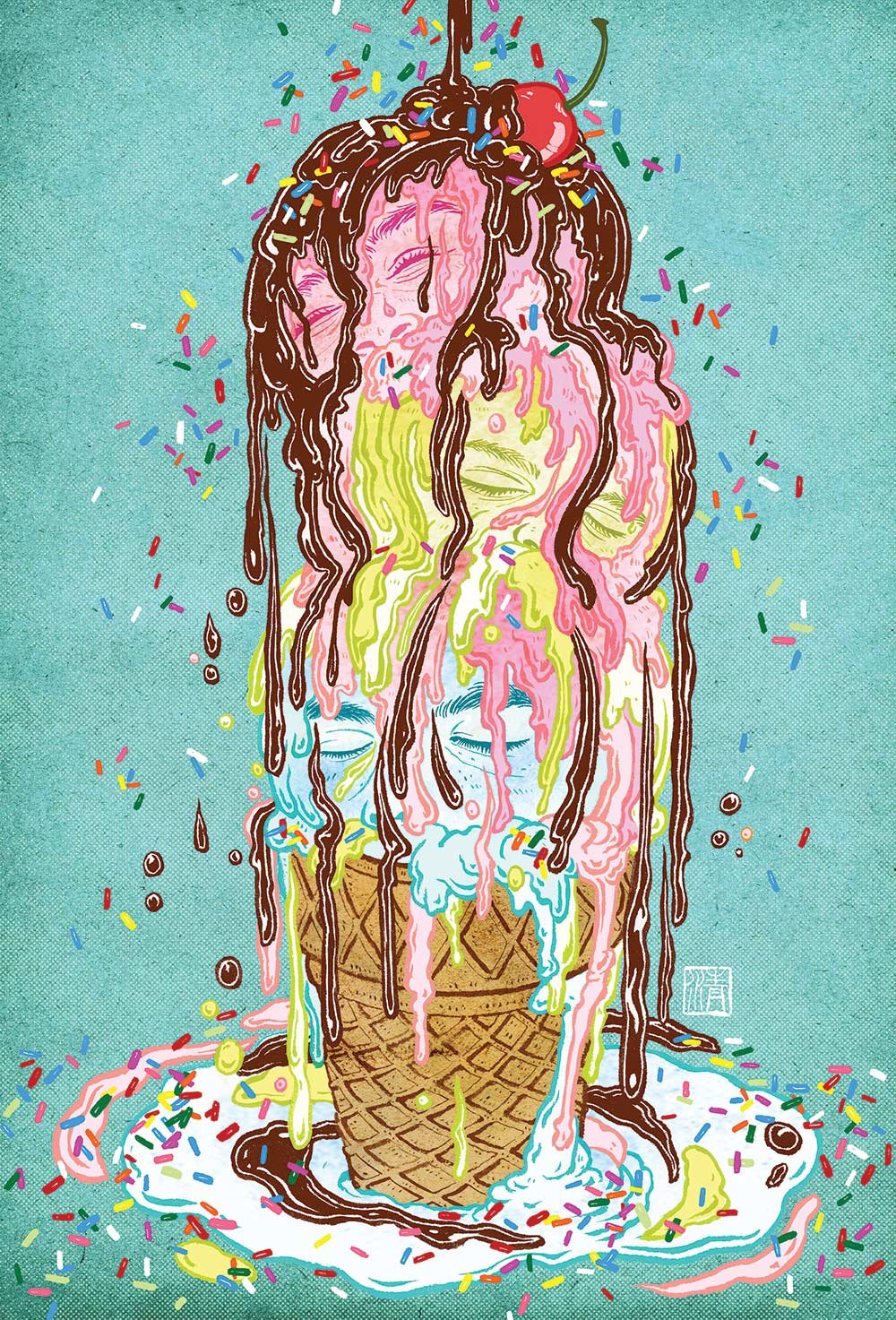

French magazine cover illustrations

French magazine cover illustrations

French magazine cover

How do you record your ideas?

By drawing

What’s your current favorite tool or material to work with?

I am not trendy. It has always been brush and ink and watercolor paper

The Cat Man of Aleppo illustrations

What book is on your nightstand? (alt: What’s the best book you’ve read this past year?)

Too many piling up, and I had to give away some books to street bookseller.

Just finished reading “These Precious Days” by Ann Patchett yesterday, and currently reading “Our Country Friends” by Gary Shteyngart. But I usually read about wars and dictatorships. It’s new year holiday, and I needed a break.

Why is authenticity in design important?

Is it? Well, I think authenticity is important in everything, but doom scrolling my Instagram, I am not sure anymore. Or, more precisely, maybe the world doesn’t feel that way?

Favorite restaurant in your city?

En Japanese Brasserie. When I miss authentic Japanese food that is not sushi (I love sushi, but sushi is not the only Japanese food!) and that is not cooked by myself, I go there. I love Japanese breakfast (not the band) they serve as brunch.

What might we find on your desk right now?

Too much paperwork piling up. ha ha.

Who do you look up to and why?

So many people, living or dead. But I tend to really admire people who do things I can never do. I particularly have highest respect for writers. Creating illustration is a solitary lonely business, but compared writers spending years alone in front of their desks…, that’s a whole another level of commitment.

Yuko in art school

What’s your favorite project that you’ve done and why?

There are things I have done in past I do like more than others, but my favorite projects should come in the future. Otherwise, why keep making? I will be better tomorrow. Always. Or, at least, that’s the attitude.

What are the last five songs you listened to?

I work alone, so I tend to listen to talk radios on WNYC or BBC World and such. I do listen to music, but mostly what’s on the radio. So, I really don’t seek to listen to songs so much anymore. Don’t get me wrong, I do love music.

Arooj Aftab is really nice. Also, Egypt’s biggest rock band Cairokee’s quarantine concert (you can find it on YouTube). Both are really soothing when I want something late at night, and I don’t want to listen to people talking.

Where can our listeners find you on the web and on social media?

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.

Clever is produced by 2VDE Media. Thanks to Rich Stroffolino for editing this episode.

Production assistance from Ilana Nevins and music by El Ten Eleven—hear more on Bandcamp.

Shoutout to Jenny Rask for designing the Clever logo.

Clever is a proud member of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit airwavemedia.com to discover more great shows.