Ep. 207: Creative Pep Talk’s Andy J. Pizza on ADHD, the Heroine’s Journey, & Invisible Things

Illustrator, graphic designer, speaker and picture book-maker Andy J. Pizza grew up in the Indiana suburbs, the child of two diametrically opposite parents - dad in corporate finance and mom an artist. Often feeling out of place, he learned to cope by drawing and smoking cigarettes, before finding indie music, and from there gig posters and graphic design. Now, he’s a wildly successful illustrator and beloved podcaster who remains exceptionally honest, open, and real about the inner workings of being a neurodivergent creative.

Subscribe our our NEW Substack to read more about Andy.

Learn more about Andy on Instagram and on his website.

TRANSCRIPT

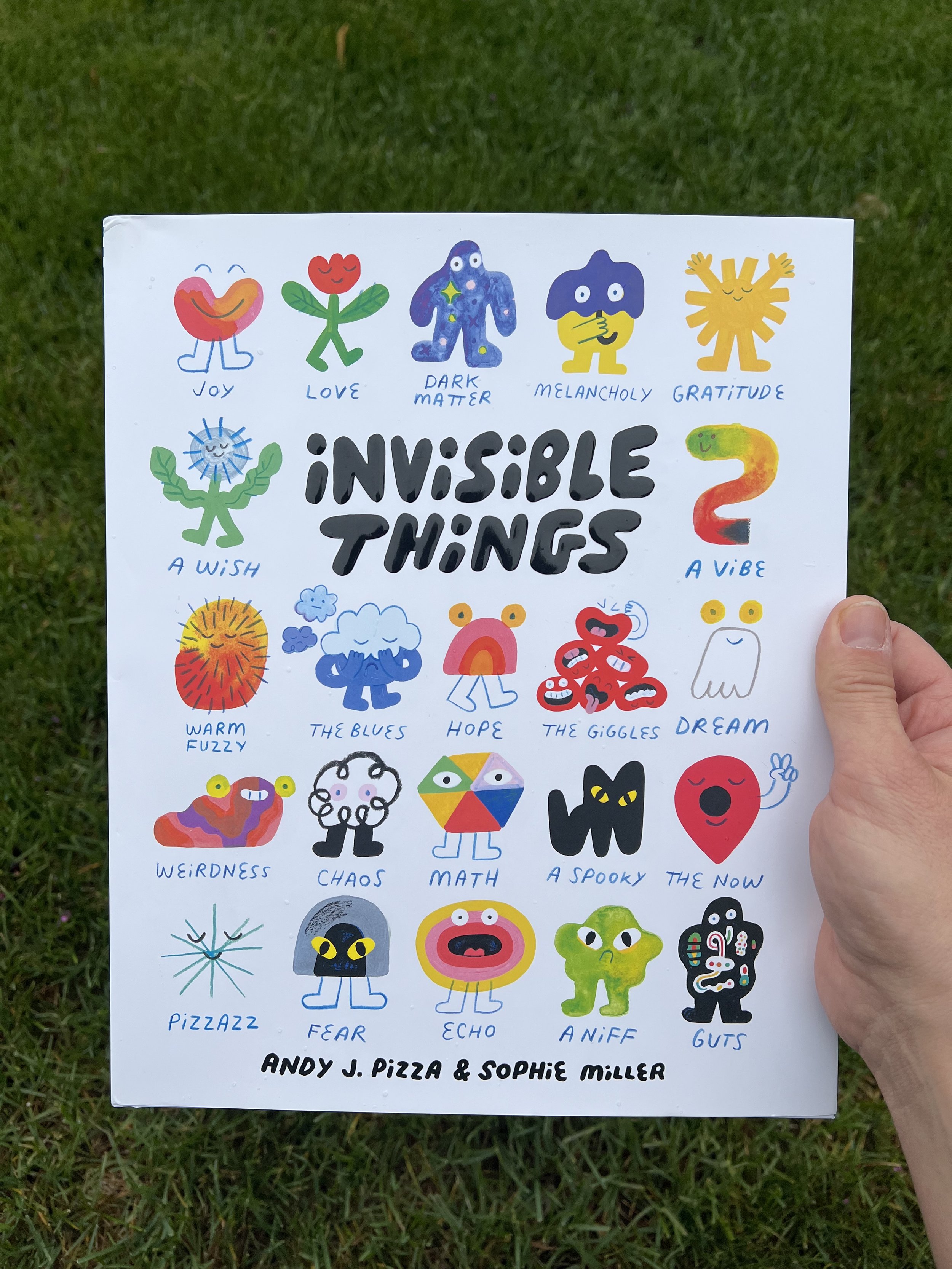

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. And today I’m talking to Andy J. Pizza. Yes, that one, the Andy J. Pizza that you know and love from his long-running podcast, Creative Pep Talk. And if you don’t know and love him yet, just keep listening and you will soon. In addition to Creative Pep Talk - where he gives you the oomph you need to continue on your creative journey by sharing all kinds of wisdom, personal philosophies and advice from other creatives, he’s also graphic designer, illustrator and picture book maker - you’ve probably seen his work with the NYT, Youtube, Google, Converse, Apple and Sony among others and he’s a New York Times Best-selling author of books for kids and adults including “Invisible Things” and “A Pizza with Everything On It.” On top of that, he does speaking engagements all over the world, is a father of 3, husband, neurodivergent with ADHD, and a profoundly delightful personality - thoughtful, perceptive, self-aware, and funny… here’s Andy.

Andy Pizza: My name is Andy J. Pizza, I’m an illustrator and storyteller and I live in the Columbus area in Ohio. I make picture books and I do a podcast called Creative Pep Talk. And over the years, over the past 15 years I’ve done a lot of client work as an illustrator as well.

Amy: You are quite accomplished and you’re also very prolific in terms of distilling your creative practice and all of the things that get you moving and also the things that hold you up and you share that very generously with your Creative Pep Talk audience. And you’ve also been through it in terms of finding your own creative voice. I really always like to go back to ground zero to figure out what you’re working with? What kind of situation were you born into that then you learned to navigate, to become who you are now? So let’s go back to your home town, your family dynamic and all of that.

Andy: Yeah, I grew up in the southern half of Indiana, in the suburbs. Both my parents came from pretty poor families. My dad ended up working up, by the time I was kind of a kid or a teenager, we were in the middle class and then he’s been really successful, even more so since I left the house. My mom kind of had the opposite trajectory. They didn’t stay together very long. It’s kind of a miracle that they procreated whatsoever (laughs), that I exist because I feel like my DNA is quite unusual in that my dad is this corporate finance guy and my mom is kind of a tragic artist type. She struggled with addiction and started several families that she couldn’t stick it out with. And so I didn’t get to see her a lot growing up. I don’t see her very much anymore. But even though it’s come with a lot of baggage and a lot of like, you know, feeling… like I’m two people, even just be one person that is this bag of DNA has been kind of bizarre. Even though that’s come with issues, I am on most days, pretty happy to be this weird combination of things. My mom and dad stayed together for just a few years, had my older brother and then had me and then she kind of moved on and did her own thing.

Amy: Okay, I’m insatiably curious about people’s upbringings, because I feel like it’s in adulthood and through creativity that we end up processing all of these emotions that we didn’t know what to do with when we were little. First of all, for context, was this in the 80s? When were you born?

Andy: Yeah, it was 1986. I’m pretty open about my childhood, especially my relationship with my mom because that had a massive impact on why I chose to create the podcast I created and why I chose to pursue a creative journey or a creative practice at all.

Amy: I mean as a young boy with an older brother and now as pretty much a solo dad, how were you getting your needs met?

Andy: I’ll tell you what my therapist would say. All of my behaviors like… I just had to do a lot of things like… I’m ADHD, I’m really open about that on the show and I would say when I was really younger, it would look like going to the nurse a lot, just to go, get a break from the classroom or from whatever. And also coping through a lot of self-soothing kind of techniques, like drawing. I think that was probably a big part of it… you know a lot of times ADHD people get put with this idea of having this super power of creativity. And I do think… I get where the novel associations come from, when you have just such a mind that doesn’t have good boundaries. I think that makes sense. But I also wonder how much of it is just the fact that it’s the way we survive the boredom of every life. Is just we’ve worked out the muscle of creativity. If we’ve managed to survive, which not everybody does with it, we’ve done so by playing games in our head and finding things to think about and creating videos and just you know, figuring out how to get by. So I think I was a really needy kid. I was a very needy teenager and yeah, I think part of the way I got through that was probably a lot of ‘misbehaving,’ I’ll say, in quotes.

Amy: Wait, when you put it in quotes, what does that mean, just like lightly reckless behavior or like nice guy bad stuff?

Andy: (Laughter) Some of it was probably genuinely very reckless. There were definitely things that I did as a teenager that I look back on and think, hmm, I’m glad I’m alive, I’m glad I did make it through there. (Laughs) I feel like I had some kind of guardian angel at different times. But I think the reason I put it in quotes is, again, back to the therapy thoughts, I think of them as protections, as they say in that world, which are, they were meeting needs that I had. And so reframing it that way helps me to think about my teenage years as not like I was a bad person. I was just a needy teenager, having to meet my own needs that were a lot more than my world was really addressing. So drugs and sneaking out, just yeah, just trying to keep myself sane. A good example that I think really hits the nail on the head is it wasn’t until later when I got diagnosed with ADHD, as an adult, that one of the psychiatrists that I worked with was telling me that nicotine is almost exactly chemically what they prescribe in terms of stimulants and growing up, by the time I started smoking, I smoked for five years, from teenage years to early 20s and I was smoking as much as I humanly could. (Laughs) I used to joke, if I would have found a genie at that time, I would have just prayed that… or I would have just told the genie, my first wish is that cigarettes were good for you, because that’s just how obsessed I was. I didn’t know I was self-medicating, and so looking back now, even though that definitely isn’t the most healthy, productive way to meet my needs, and it’s why I don’t smoke cigarettes now, I don’t have to look back through a lens of shame, I can just see, that’s what I could get my hands on and it helped me get through that stage of my life that was very difficult. I quite possibly might have not got through, if I hadn’t had some of those tools.

Amy: Yeah, I’m hearing you and I sort of resonate with a lot of that actually. I know your mom was the creative one and you also set it up like that. Your dad is the finance guy. So a couple of questions are: Clearly you’ve got both in your DNA and you’re working both of those as an adult, so congratulations!

Andy: Trying, I’m trying to.

Amy: Yeah. (Laughs) But even though, let’s say you got your creativity from your mom's side, you didn’t get a lot of great role modeling from her. What were the main issues around that, like abandonment or like what have you worked through in therapy when it comes to your mom not being there?

Andy: I think that was a big one and I think that I was a real mamma’s boy too. I grew up in a house that was… so I will say, on my dad’s side, I do think I came to realize that I… I actually when I was really little, this is a common story with neurodivergent people, which I didn’t realize until much later. But I thought either I’m an alien or my dad and my stepmom were aliens. And I used to lay in bed thinking, maybe they have like device where as soon as I see them or I get up out of bed and I go down the hall and I watch them… I see them watching TV, they have some kind of device that instantaneously turns them back into humans. I thought maybe that could be true. I didn’t think it was true, I just thought it could be true. (Laughs) I definitely felt like an alien in that house. And for the longest time I think I didn’t relate to my dad whatsoever. I loved him, and especially for his generation, he was very open about his feelings, he would shower us with love and affirmation. I’m not saying he was perfect, but…I was lucky to have him. And it wasn’t until much later that I noticed that even though I didn’t get his math skills, that I did get a lot of his integrity and kind of intension and strategy. I think I do have a very strategic mind that comes from him. He’s a very big business strategist for the company that he’s worked for. And so I bring that up because it wasn’t until much later that I realized, oh, I do have all these things that are like my dad and things relate to him with, but growing up I didn’t see any of those things. I was growing up in a family that was very corporate America, like my dad and my stepmom both worked in corporate America, climbing the corporate ladder, math heavy, sports heavy. My younger brother, he’s named Jordan, after Michael Jordan. (Laughs) They’re just crazy basketball people. And I am terrible at sports and not interested, can’t pay attention. We’d go to these Indiana Pacer games and I’m just like dancing, watching stuff. I would go there and I’d be like okay, I’m going to watch the game and then five seconds later I’m looking at the guys selling cotton candy and just… I just couldn’t do it. And so I had a deep awareness that I was so much more like my mom. And the times I got to spend at my mom’s house, I felt so at home and so comfortable, but they were a couple of weeks in the summer, for a couple of summers. There was sometimes where she lived close enough where I could spend weekends, like every other weekend with her, but those were very sporadic because she kind of moved around all over the place. And so yeah, I think I was deeply aware, even then of attachment issues. I think I was just like, me and my older brother, I think we have like classic… actually I don’t think I’ve fully healed from it, but I think I’ve learned a lot about it and I’m not as much right now. But back growing up, he had the very much reaction of, I don’t need anybody, I’m not going to let anybody.

Amy: Yeah, avoidance.

Andy: Yes, avoid and attachment and I was just that insecure kind of, I need anybody, please, I’ll give you everything, just somebody hug me, I need some love! (Laughter) I think I had to learn the hard way and learn about boundaries and that kind of thing. And luckily I think, I’ve had a really secure marriage for 15 years we’ve been best friends and trustworthy confidantes and I think that’s helped too.

Amy: That’s wonderful. I love your attitude. I must say that when you go back and review all of these hardships, then they were. I know that they must have been very hard. But you always frame it as though there’s a happy ending and you’re deeply seated in your happy ending right now.

Andy: Yeah.

Amy: There’s a joyfulness that comes through in even your tragedy and I think that’s a really, really great characteristic.

Andy: Yeah, I think again, that’s a thing that I get from my dad. And ultimately what I think that is, is storytelling. And I think I say this, joke a lot, but there’s definitely some truth to it where storytelling is what I consider to be my religion. And you only have to have a passing interest in story to start realizing that that’s kind of how we make sense of the madness of reality. It’s the way our brain can understand and kind of find meaning in the chaos. And I think a strategic mind is particularly interested in storytelling because I think a lot of good storytelling starts with the end in mind and kind of works backwards. So I think there’s a thing about reframing that comes natural to me. And I don’t want to misrepresent myself, I’m also a deeply emotional creator who has terrible days where I’m cursing my existence, (laughs) I have those days! But I try as often as possible to reground myself in story. And I think the other great thing about story is that if you think about it kind of like an equation of act one, act two equals act three, it’s not a Pollyanna-ish blind toxic positivity. Like act one and act two, act two being where the conflict is, to get to act three you have to integrate them. You have to make them part of the experience. And so yeah, even though I think that I do see a lot of purpose in that journey and in the pain that I have with my mom, I don’t think that I just blind myself to the reality of how it’s shaped me and how it’s a problem that I have that won’t really ever fully go away. So I don’t know if that makes sense, but that’s kind of… yeah. This is also what it makes possible because I feel, one kind of story way that I’ve thought about it is, those same deep pains that feel like these holes that have been dug into your soul end up becoming the well of passion that you have, to help others. And it really does. When I meet… anybody that’s made podcasts as long as we have, have had to find serious fuel sources, right?

Amy: Yes, thank you for acknowledging that, for sure, oh my god, I can’t believe I’m still doing it! (Laughs)

Andy: Same! It’s a crazy… there’s so much more to it than I ever would have guessed and it’s a rollercoaster. And I think for me, my relationship to my mom and her ADHD and being a creative person and that being such a difficult thing to be in the world, is why I can continue to make podcasts. I met my H-vac guy, who was a veteran, but also it came out that he was ADHD. And as soon as I start putting these pieces together, I can feel the weight of what it feels like to walk through a world that was not built with you in mind.

Amy: Back to the cigarettes and the teen years, the needy teenage years. Was that also when indie rock became a sort of steady companion for you?

Andy: Yeah, looking back I can see that there’s a period of time when I was really little, that I loved being like my mom. Then there was a period of time where as I watched her life fall apart, being like her started feeling like a curse. It felt like okay, so this, it sucks to be like these kinds of people, and that’s what I’m like. (Laughs) So I think from my late teens into my early 20s, I was trying to get my life together and that period of time I was really trying to be anything but myself. How am I going to get over being the type of person that I am and the person that my mom is? And so I was really trying to find, how am I going to be employed? How am I going to stick with a job and a relationship and all those kinds of things that my mom can never seem to do. I got a part time job and I’m like, I’m going to stick at this. My first job was at a movie theatre. I had a few different roles. Whenever they would have me at a cashiers box, I would lose tons of money, first of all (laughs) and feel tremendous shame because I’m like, I know I can do math, there’s just something about the combination of things happening here that means it doesn’t matter how much I try, I can’t do this. And so the times where I would get to clean up after the movies and stuff, and walk around and do that, it was definitely better. But even just like being indoors under fluorescent lighting for more than five hours is a challenge for me today. So like even now, I try to mix it up and build in breaks and stuff like that. I would stick at things, because you know, I watched my mom just drop things all the time. Even if they were things that weren’t good for me. But, as I’m thinking, I’m going to will myself into being a different person, but I’m really struggling with my job to the point where I’m like, starting to get into a very dark place of, all the futures seem worse than where I’m at right now.

Amy: Oh, that’s the worst.

Andy: It was really bad. And it was right around that time that I discovered indie music and this kind of alternative culture and gig posters and design. And I didn’t think… I was like, I don’t know how successful these people are, but it seems kind of like a job and a job that maybe I could do. So that started my creative journey into illustration and design and deciding to go to school for that and all that kind of thing.

Amy: Okay, I like that the visual culture of a creative medium… is what brought you into it. Had you before that, had you even understood that graphic design was a thing or that illustration was… I mean draw, but was illustration a career that was on your radar?

Andy: I think the only piece of that that maybe was when I was like in elementary school, was picture books. I did have a very profound experience with a handful of picture book author and illustrators, people like Shel Silverstein, Dr Zeus, then a little bit later Jon Scieszka, I think probably some level thought that maybe that was a path. But everybody… growing up in the Midwest, in the suburbs, nobody knew anybody doing anything creative for a living whatsoever. The only job that anybody kind of knew about, were like, why don’t you get into animation? And I was like man, that just seems like a lot of time sat in a chair.

Amy: Yeah. (Laughs)

Andy: I knew I couldn’t do that, even though I would draw a lot, but I was always making stuff. I was always making videos and this is before when you were actually making them on like VHS and trying to create that way. So I was always making stuff, but I didn’t really find a path towards any kind of creative practice until I discovered the Pacific North West Indie culture, Modest Mouse, Death Cab, the Shins, all that kind of stuff. And I didn’t play music, and so I gravitated towards all of the rich visual culture and the poster design and all that kind of stuff. I thought, I think I could do that, and I was super into it.

Amy: And so then you pulled that thread to school?

Andy: Yeah. I got really lucky in that at the same year I graduated, my dad had an offer within his company to do a role overseas in Britain for a few years. And they were like, hey, do you want to try to go to college there? And the main reason I said yes, other than I think I had a romantic version of what England was, as most Americans probably do. Other than that, I found out that in their university, it’s a three year program and there are no general studies. And so I was like, all right, I’m in! Go straight into creative stuff all the time, I am all in. And I’m really glad I did that because I don’t know, who knows if I would have survived the college years in America and the math course with that much freedom, I can’t imagine myself going to those classes. But yeah, that really worked out. So I went to a school in the North of England, Huddersfield University and yeah, it worked out really, really well.

Amy: Is this also where you met your wife?

Andy: Yeah, and so we both went to that school. We both were doing creative subjects. She did fiber art. But we met doing a different type of art. I don’t know if you’re familiar with this art form? It’s sandwich art, it’s Subway… (Laughter) We were Subway sandwich artists. We worked at… it’s very romantic. We worked at Subways, across from town and so there were a few times where I met her in passing, the stores came together to do like a sandwich-off, to win a bike that had a big Subway graphic on it. And so I met her once like then, maybe one other time, but it wasn’t until our final year that she ended up taking some shifts over at our Subway over the summer and we… I think at the time, because of the stuff with my mom, in high school and all that, I dated a ton and I was just like very interested in having a girlfriend. And so when I went to college and I got into art and I got serious about life, I really quit dating and I really kind of thought, I don’t really know if I am feeling like any of this romantic stuff is a thing. I think it’s kind of like a Hollywood thing and I really didn’t believe in romantic love. Then I met her and fell… we fell harder in love than I’ve ever seen two people fall in love. And then just kind of went into this crazy creative hibernation, all that year, like spending tons and tons of time together, in the same room, working on our different creative projects and really having a creative impact on each other. It was a big deal, I think, in all kinds of different ways.

Amy: I love that love story. I want to hear how you and Sophie Miller fell in love, impacted each other creatively and then somehow landed in Columbus Ohio, connect those dots for me and the start of your profession?

Andy: One of the things that really has defined our relationship… I mean both as partners, but also parents and then creative collaborators is I have all of this energy and I want to start things and I have a million ideas and I’m not great at finishing things and I also have a hard time choosing a path. And so I can come up with a hundred ideas. I have a really hard time knowing which to focus on and to see them through. And I think even from the beginning, Sophie was one of the first people that was just really honest, and this is our relationship to today. If I want a compliment about my work, I’m going to go to somebody else. If I want to know the truth about it, I will show it to her. And I’ll be like, what do you think about this and she’s going to tell me what she really thinks. And she’s always helped me find a path in order to actually make progress. To actually do something, make it, finish it, put it into reality. Because if it hadn’t been for that relationship, I honestly think I would still be going in 10 or 15 different directions at the same time and not really finishing any of them.

Amy: Wow, that’s a marriage of complements, for sure.

Andy: Because of having this public facing side of my practice, I always try to represent things as accurately as possible. And I would just say, that part of that relationship is incredible. She is the person that I’m closest to, but being two artists is a crazy choice. It’s crazy…

Amy: Yeah, I’ve done that before too.

Andy: Yeah, and sometimes when we collaborate, we’re going to really have serious arguments about what we’re going to do and how we’re going to do it and all that. And I think the work is almost always better for it, but we’ve had to learn a lot about how do you do this in a way that is constructive, not just for the work, but also the relationship.

Amy: Yeah, wow.

Andy: Because it’s not easy, it’s very difficult and I think we still have plenty to learn on that, myself primarily on that front.

Amy: Well, more power to you on that. I’m just kind of curious, your reconciliation with ADHD, did that come about during the relationship or prior?

Andy: Yeah, it did. We got married, started having children. We wanted to then move to the States because there were a lot more opportunities with the kind of thing that I was pursuing and Sophie wanted to… while we had little kids, primarily focus her energy that way. It made more sense to do it in the States, so we moved back to the States, ended up in Columbus Ohio. And I taught a few art classes at the art school here, Columbus College of Art and Design, that was also kind of a good benefit to have that base. And so when we first moved back, I had some momentum, I was getting some jobs, getting some illustration work. And then for a combination of a few different things, shortly after we moved back, all of that work just dried up. And so I think it was in the recession of ’08, so that was part of it.

Amy: Yeah, two kids?

Andy: We had one kid at the time and we were expecting another shortly after, now we have three kids. We really had low overhead, but we kind of bet on this lifestyle and this path. And it kind of just blew up in my face. And I’d tried all kinds of things to get the ball rolling again. But a lot of the trends I was working in at the time, like I had just started out. I didn’t really have a good sense of my voice. I was just kind of doing commercially driven work. And yeah, a combination of things meant that for about six months I didn’t get any jobs and ended up having to just take whatever work I could find. And I was working at a youth shelter, juvenile detention center, which is kind of ironic, because work already feels like jail, to then go actually work in a jail was a whole other thing. (Laughs) And that was kind of a rock bottom, where I started obsessively consuming both business content and also content from creators and this is before social media is what it is now. So it mostly looked like interviews with creators and talks that they gave. And I was just consuming everything I could find. And when I was really getting low on creative fodder for this fire that I was building, I came across this talk of this origami artist, Joseph Wu, and he had just got diagnosed with ADHD. And I had avoided watching that talk for a long time because I had suspected that I had ADHD as far back as maybe first grade. I had a buddy who was the only kid that I knew with the energy I had, with the absurd humor I had, and I just thought, this guy is awesome. And then one day he’s like, hey, I’ve got to go get my meds and I’m like, what’s wrong man? And he’s like, “No, I’m just hyper.” I was like whoa, I thought this was a good thing. Like I didn’t know this needed to be medicated. (Laughter) And then in high school I’d once taken, when I was kind of in my drug phase, I’d taken Adderall recreationally and I make the joke that me and my friend took it, both went home, did crazy things, like he stayed up all night and watched the sun rise, like shaking and I did something crazier than that, which was my homework. (Laughter) And I did it efficiently. And I thought, hmm, that’s weird, this is not having the regular effect. But I didn’t know what to do about it. And also I think I spent a good decade trying to overcome who I was. Trying to escape who I was. And a diagnosis is kind of looking at the shadow kind of thing.

Amy: Right.

Andy: And so it wasn’t until seeing that talk, and being in this really low place… I don’t know how I’m going to provide for kids and have a job and do all this stuff. It took all that to kind of start to open that door seriously.

Amy: Wow, that’s gripping. As you mentioned working in the juvenile detention center, did you see a lot of juveniles that you suspect had undiagnosed ADHD?

Andy: Yeah, I did and they had all kinds of different things, honestly, oppositional defiant disorder is a big one in there and all kinds of things that can kind of get you in trouble. I think a lot of… I’m not an expert at all, really, other than just lived experience with being neurodivergent, but I think also people with dyslexia and autism have a lot of rebelliousness because they can’t survive in the regular system. So I was seeing a lot of that and I do a lot of talks and so I put some of this stuff in that and I work out material on the show also. And so I’ve given it a lot of thought. And I think a lot about that moment… actually going back to how I use story to kind of get through life, I’ve thought a lot about working at the juvenile detention center, because it was the most literal facing of the fears because I was so desperately afraid of work, because it felt like jail. Because it felt like being locked up. To ending up having to take a job in a jail, there’s some poetic symmetry there that I’m like, okay, what did I learn from that? And I do think it contributed to being around kids… recognizing kids acting out because they had needs that weren’t being met. I think that was a big part of it. But I think ultimately my biggest takeaway with ADHD and I think the thing that really changed my life was a change in my lens on how I saw myself and how I saw people, from being the better version of yourself and growing, won’t happen from seeing yourself as a bad thing that needs to be crushed. Versus seeing something with potential, that’s ultimately good, that needs directing and channeling, but also cultivating. And I think the thing that I saw at that job was… it was almost like working in an experiment because I took that job, partially because I didn’t have any other choice, but also because I thought I was taking a job at the youth shelter and the youth shelter is a different side of this building where they take in kids because every kid deserves to have a roof over their head. So when a kid, when a teenager, their life at home wasn’t suitable or they were homeless or whatever, they would be taken to the youth shelter because they deserved the dignity and respect to have a place to live. And so I thought I was taking that job. But what I found out later was, you actually were required to take shifts on the other side of the building, which was the juvenile detention center. And I avoided that as long as possible because I knew it’s like, this is fluorescent lighting, almost no windows, locked up for 10 hours at a time. And I avoided it as much as possible, but I’m glad I had to go through that because what I realized was they were the same kids. So the kids that were at the youth shelter would end up in the detention center and the detention center would end up in the youth shelter. And the narrative that everybody knew from working there, was their behavior is determined by not who they are, but which wing they’re in. And I realized they could be in the exact same place and how they dealt with it would be different depending on why they thought they were in the position that they were in. Were they in the position they were in because they were a good thing that deserved to be taken care of, or were they there because they were a bad thing that needed to be locked up? And so…

Amy: That’s profound, yeah.

Andy: There was this big…oh, it’s not the person, it has so much to do with how they see themselves and how they see their circumstance. And again, I don’t think I had words for it until I started digging into that later, but I think that contributed to being willing to look at myself in the mirror and kind of think about, why do I have these struggles, why do I have these needs? And then as I started diving into the ADHD stuff. I also saw my mom and so growing up, the narrative around my mom was she’s bad… I don’t think my dad… to my dad’s credit, he was never one of the people saying that narrative. Everybody else was. And he really had a lot of good reasons to say that. He probably had been hurt by her more than anybody else, other than me and my brother. But the narrative around my mom was, she can’t stick to anything, she’s a bad person, she’s abandoned two families, she’s never been able to keep a job and then as I’m starting to dig into this, I actually start asking my dad things and realize, oh, it wasn’t just that she couldn’t keep a job, is that she tried to do these things. She tried to be a waitress, and guess what, just like me at the movie theater, would constantly lose money and she would be ashamed. It’s shameful to not be able to do simple math and the basic… the first level job you can get. And so I started to realize that oh, she’s not failing at who she is. She’s not failing because of who she is, she’s failing because she’s trying to be something she isn’t.

Amy: Yeah, yeah. She’s working against her nature.

Andy: Yeah, and her strengths and so yeah, I think my biggest thing as an artist and kind of the work that I’m exploring doing next is really about a fundamental shift from a negative personal psychology to a positive one because I do think it has a huge shift and a benefit.

Amy: You changed your whole lens. I’m curious about this journey you went on in terms of being willing to face your fears and look at the shadow side. And how you approached that, where you found the courage to stay on that journey. Were you having epiphanies along the way that… I mean that’s the thing about that journey, is it’s incredibly uncomfortable, but when you find aspects that you really relate with, it also feels like oh my god, this puzzle that I thought was unsolvable, now has a potential solution. I just need to look at it differently. And that’s amazing. That’s really hopeful.

Andy: Yeah and I’m still on that journey because I think what it looks like to channel and cultivate self, it’s a huge task and it’s always going to be difficult. And I like to think, in some ways I think about it through the metaphor of Water World, that old Kevin Costner movie where some people evolve to have gills and they’re suited for this world. And then other people didn’t and need a snorkel and it’s okay, it’s okay. That’s okay. So sometimes that looks like self-compassion and being like, hey, I need this thing, it’s maybe not the ideal thing or maybe it would be good if I didn’t need this. But I do, and so self-compassion, I think looks like that. But ultimately working through this as a story, the line that is kind of one of my favorite things that’s come up in writing and doing talks on it is I can look back and see this was a massive turning point for my creative practice. Like I said, before that I was working in trends. I honestly think going to school, and also growing up in a religious setting, the one I grew up in, I think gave me the lens of you’re a bad thing. And you are a thing that needs to be controlled, repressed, whatever. And that’s how you’re going to get to be acceptable. And I think that even going to school for art, I think it was a conflict of like, okay, how can you make art and not want to look inside? I think I always felt complicated around that. Whereas once I started this path, I started to be able to be more curious about myself. And I think that’s a thing that happens with the shadow side in general is, if you’re not willing to look at that side of yourself, you’re really missing everything, you’re missing all kinds of things that you don’t even know that you’re missing. And the line that I wrote, that is kind of central to wherever this project goes… Art is self-expression and you can’t make self-expression that you love if you hate the thing that it expresses, which is self. You can’t hate yourself and make art that you love. I think this shift was also the beginning of finding a more authentic path to a style and a substance and stories that were more truly mine. And so I think that that journey also went hand-in-hand and was a big ongoing breakthrough for me as a creator.

Amy: I love it! It sounds like it’s a part of your practice now, part of your process. And from there your career really has taken off.

Andy: Yeah.

Amy: I do just want to highlight for our listeners (laughs) that you’ve become really good at what you do and you’ve been working steadily, illustrating kids books and illustrations for Apple and New York Times and Nickelodeon and recently released a book called Invisible Things, which is just a delightful catalog of invisible abstract forces and feelings and things that can’t really be described visually and yet having your visual characters represent them helps us understand them better. Helps us name and helps us feel also, well if somebody drew grief like this, then grief is natural, grief is okay and grief is not necessarily an enemy that needs to be avoided, it’s just a different kind of friendship.

Andy: Yeah, that’s a project that’s been in the works that has been a collaboration with me and Sophie since I started it, since I came up with… I came up with the first one, she came up with the second one, all the way back and probably over 10 years ago. And then it was released as a picture book last year. And yeah, I think that there are these social/emotional applications for kids, things like emotional distance, that’s a thing that’s really useful when processing emotions, is trying to get kids to not say ‘I’m anxious,’ like identifying with your anxiety rather than saying, ‘I’m having anxiety.’ So giving a face and a name to those kinds of things helps you get a little bit of distance and see, kind of the same way that a creator might think about their inner critic, instead of being like, that’s me tearing myself apart. Thinking, oh, that’s that voice again, oh, I’m noticing, I’m observing it and just getting a little distance. But like I said, it’s been a decade in the making. The more I’ve got into it, the more I’ve started to realize that this is a practice that we’ve done since recorded history, which is personify things we can’t see. You can go back to, even just a great example are the Greek gods and goddesses, what would war be if it was a person? What would love be if it was a person? I think putting a name and a face just helps us have a relationship with those things. It’s the same thing as the thing I said at the start, which was the protections. The idea of making friends with the addict part of myself, like that actually is, again, it’s a type of positive psychology… it’s not to be confused with toxic positivity…

Amy: Yes.

Andy: Because that’s very different things. But a positive psychology says, well you didn’t do these things because you were bad, they were there to help you at the time that you needed them and if they’re not helpful anymore, maybe you need to change your relationship to them. It kind of falls into that camp as well.

Amy: You seem like a very evolved creative (laughter)…

Andy: I’m trying man, oh my gosh! I am trying!

Amy: Well, so that’s my question, what tools are you using in this active evolution, in this, I guess, spiritual self-actualization?

Andy: Yeah, it’s looked like a lot of different things over time and I’m an ADHD person, so I have these hyper-focuses, where I’ll go deep on something for a long while, that was like Joseph Campbell, The Hero’s Journey, story structure, that kind of stuff, that was a good section of my life and I would say most recently I’ve kind of had a massive deep dive into Jungian archetypes and dreamwork and I actually am kind of blown away, like legitimately blown away that Jungian, psychoanalytic approach to symbols isn’t a bigger part of the design conversation, the illustration conversation, because I think this is it, this is what we’re trying to do.

Amy: I absolutely 100% agree with you. If we could talk a lot more about archetypes and symbolism, we could have a much deeper, richer universal creative language that we could build from.

Andy: I think it just took me a long time for it to click what this was, especially in terms of symbolism in the depth of its power within visual art. I think I just didn’t understand it, and so I wonder if it’s just resources or different ways of communicating and educating what these things are. Because I definitely had a class that went into semiotics and signs and symbols and all that kind of stuff. But I didn’t understand what they were talking about. So I don’t know, but yeah, I would say Jungian stuff…

Amy: I agree with you, I think it gets framed in different ways. I think in literature, they deconstruct the symbolism for what its deeper meaning, in let’s say an acting class you might use archetypes as a way of pulling from yourself something for the character. And then when it comes to Jungian, it’s probably in a psychology class. But they never get brought into general creative technical design studio philosophy theory.

Andy: Yeah. I think the cross-pollination of… also from doing the podcasts, I ended up becoming more and more in touch with studies of creativity and trying to dive into that world and try to get words for some of the things that work for me or work for the creators that I’m a huge fan of. And one of the things they talk a lot about is the cross-pollination of different disciplines, right? I think it would be really powerful. But then also beyond creativity, what I’ve loved about depth psychology is there are a lot of frameworks that are very non-dual kind of seasonal approach to life. I think one of the things that has fallen short in some of the philosophies that were given to me growing up were that they didn’t account for, you need different things at different times of your life. And so when you’re in your late teens, early 20s, all the way to 30s for me, you do need ego formation, The Hero’s Journey, become the individual, find what you’re good at. Do that kind of thing. But then you can become the kind of hero that just wants to know where the next dragon is until you get killed. I think of it through a creative lens, I think there’s an there’s an obsession with this phase, like 18-25. And so it’s all about how do you stay there? How do you stay at your peak and whatever it is, and I think instead of saying okay, having an idea of the seasons of life, it ends up feeling like kids arguing about summers best, winters best… none of them are best. There’s a time for each one and I do think, even living in England I felt like they seem to have a better sense of, like here’s what’s good about being in your 40s, and that’s a generalization and it could just be the people that I knew. But I definitely think there’s kind of an obsession with this… The Hero’s Journey, there’s an obsession with this phase in your life where you’re becoming a master at being an individual and being part of the team and being part of the community is seen as something to… that’s slowing you down, that’s going to hurt you, that’s going to hold you back, that’s going to tame you, whatever. There’s a good book that I just finished… I’ve read two books on The Heroine’s Journey. The most recent one is by Gail Carriger and that book goes deep into… The Hero’s Journey is typically about becoming an individual, not receiving help, any type of connection is trying to weaken you. And then she’s making the point that The Heroine’s Journey, and it’s not gender based, it’s not sex based, it’s just two different energies and two different ways of thinking about them throughout, storytelling throughout time. And The Heroine’s Journey, and you can identify any type of gender and go on a heroine’s journey, and a heroine’s journey is learning to ask for help as a strength. Finding connection as a strength. Networking is a strength. And isolation is where you’re weak. And so yeah, I wish that we had more access to a more non-binary, non-dual way of going through life where what you’re… you either think this or you think that. Because you need different things at different times.

Amy: Absolutely. And I also think that The Hero’s Journey is a really powerful story. But The Heroine’s Journey, which I’m going to read those books, please send me the links, if you think of a community and if it’s only competition within the community, then the community destroys itself. And what are you left with? A sole hero that gets to claim they destroyed the community? But if the community is interdependent and supports itself, then the whole community stands a chance of not just elevating everyone within the community, but expanding and becoming a self-sustaining ecosystem that’s harmonious and diverse. And so I often think about that and how particularly in this western US capitalistic culture we’ve created a way of being that is about dominating nature and subverting it rather than co-existing and living in a synergistic environment with nature and animals. And factory farming is just fucking ridiculous! (Laughs) Why and how?

Andy: And it’s a violent, hyper individualist way of being. And I think what’s interesting is, the interesting piece is that you need both at different times. There are times when falling into the society is a sickness. There is a time where you have to break the mold. It needs to ebb and flow and I feel very grateful for my time in the UK and I try not to generalize that because I lived in the north of England, I was hours away from London. My experience was extremely limited. But it felt very much more like the ‘we centered’ versus the ‘me centered.’ When it came to Covid, people tended to all agree, this is what we’re doing and we’re all doing it. And again, this is just my own take, I don’t even know if there’s any weight to it, but when you watch reality TV in America, like a game show, the American equivalent of British Bake-Off, it feels like typically the stand-out celebrated person is the most individual. Like the charisma, so unique. With British Bake-Off I feel like, at first I would be like, what’s happening where the people they’re championing are like, ‘you’re the most British, you’re the most like all of us.’ And you’re like… I’m just like… what the… I’ve never seen people get celebrated for being the most epitome of normal. So I think yeah, there’s a give and take and I think right now it feels like in America, and I’m not qualified to say it, but I do feel like it’s grounded on a hyper-individualism. It would be good to get some heroine’s journeys.

Amy: Yeah, I agree. I’ve started paying attention to masculine and feminine energy, as you were talking about. We all have both, right?

Andy: Exactly.

Amy: I think one of the things we could, as Americans, be a lot better at, is identifying both within ourselves and working with it to balance it harmoniously, so we know when to be receptive and we know when to be directive and we also appreciate being directive because we’ve gotten an intuitive hit or something that’s a little bit more feminine. And I feel like we’d all be, I don’t know, a little more peaceful and centered and probably precise if we were to be able to master both of those sides.

Andy: Very much so. And I’ll just do one more plug for Jungian psychology because if you go read his original stuff, there are ways in which it’s very much a product of its time and some of the masculine/feminine conversation is lacking and not super evolved and nuanced. However, no matter how you think about yourself, there comes a phase where… one of the phases down the road after The Hero’s Journey, is integrating the opposite side. The union of opposites. So whether you’ve lived a very masculine journey or a feminine journey, there’s going to come a time where you need to integrate the anima or the animus, the inner feminine or the inner masculine and that becomes a whole other phase. And so yeah, I agree with you.

Amy: Is that where you are right now?

Andy: That is where I am at, yeah. I’m trying to figure out the feminine… The Heroine’s Journey because I do… I want to build team and I want to be a collaborator and I think doing the book with my wife was a big part of that. Of like, I don’t want to do all this stuff alone because according to Gail Carriger, the hero’s journey ends with them sacrificing themselves and being alone. (Laughter) I don’t want that! I don’t know anybody that does! That’s not where I want to end up.

Amy: It’s been written… you can see how it’s going to end, is that the ending you want?

Andy: Yes, exactly. (Laughter) I’m trying to figure out some of the other, because that’s not where I’m trying to go.

Amy: Well, I would love to join you on this heroine’s piece of the journey. I love what you’re doing. I’m so glad you’re putting it out in the world. I know podcasting can be kind of lonely and also having a studio to yourself can be kind of lonely. But it’s very clear to me that there is a generosity in how you’re living your life and everything you’re putting out into the world. And so I just want to thank you for that. I think it’s awesome.

Andy: Hey, same to you, you’ve been doing a lot of giving freely with the podcast you’ve created and been a part of for all this time and I think you probably have no idea the amount of people that you’ve kept company and that really matters, so thanks for letting me part of it too.

Amy: Hey, thanks so much for listening for a transcript of this episode, and more about Andy, including links, and images of his work - head to our website - cleverpodcast.com. While you’re there, check out our Resources page for books, info, and special offers from our guests, partners, and sponsors. And sign-up for our monthly substack. If you like Clever, there are a number of ways you can support us: - share Clever with your friends, leave us a 5 star rating, or a kind review, support our sponsors, and hit the follow or subscribe button in your podcast app so that our new episodes will turn up in your feed. We love to hear from you on LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter X - you can find us @cleverpodcast and you can find me @amydevers. Clever is hosted & produced by me, Amy Devers, with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever is a proud member of the Surround podcast network. Visit surroundpodcasts.com to discover more of the Architecture and Design industry’s premier shows.

Andy J. Pizza

Invisible Things by Andy J. Pizza and Sophie Miller

Andy hard at work!

Andy and his wife and creative collaborator, Sophie.

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.